OR

Shiksha Risal

Risal has been practicing journalism for the past seven years. She writes on social issues, social media, IT and literature. Currently, she is associated with Nagarik daily.news@myrepublica.com

On August 25, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, formerly known as Harakah al-Yaqin, led coordinated attacks on police posts and army bases on the northern Rakhine state of Myanmar. This led to the death of 12 security officers and 77 Rohingya insurgents, according to the government. Following the violence, there has been a mass exodus of Rohingya population from the state of Rakhine. While the Myanmar army calls it an action against insurgents, the international community has labeled it genocide. Till date, it is reported that nearly 400,000 Rohingyas have crossed the border into Bangladesh, while many are still trapped inside. Nearly 100,000 of them are internally displaced while 40 percent of their villages are empty. The UN High Commissioner called it “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”. The international community has voiced its anger and concern for these ethnic minorities. Myanmar’s leader Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate, is now facing growing criticism over the issue.

On her first official statement on the crisis, Suu Kyi stated on September 19 that she felt “deeply” for the suffering of “all people” in the conflict, and that Myanmar was “committed to a sustainable solution… for all communities in this state”. She also stressed that her government does not fear “international scrutiny” of its handling of the growing Rohingya crisis and said that most Muslims had not fled the country, and that the violence had ceased. The statement came after Suu Kyi decided not to attend the UN General Assembly in New York.

The 1.1 million, mostly-Muslim Rohingyas are considered among the world’s largest and most persecuted ethnic minorities. Following Myanmar’s 1982 citizen act, the Rohingyas were denied citizenship. Despite being able to trace their origin to 18th century, the Myanmar government does not treat them as one of their races; they are primarily believed to have moved in from Bengal and are considered “illegal immigrants”. They have restricted freedom of movement, education, healthcare and jobs. Sectarian clashes are common between Rohingya Muslims who are majority in the northern part and the Buddhists Rakhine population who have majority in the south. There is a widespread fear among Buddhist Rakhines that they will soon be a minority in their ancestral state, not just in the northern part.

Overwhelmed Bangladesh

As a result of such clashes, many Rohingyas are forced to leave the Rakhine state and cross the border and there are an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 Rohingyas in Bangladesh now. Only 32,000 of these Rohingyas are registered with the UNHCR and Bangladesh government. Most refugees are concentrated in or near Cox’s Bazar, a coastal area near the border. Since the latest violence on August 25, Bangladesh has seen a massive influx of Rohingyas, with thousands crossing the border every day, and this has caused an additional burden to one of the world’s poorest countries with an annual per capita income of just US $1300. Conditions are worsening in Cox’s Bazar where the influx has added pressure on Rohingya camps and pushed aid services in Bangladesh to the brink, which is already overwhelmed with more than 300,000 people from earlier waves of refugees.

Not just Bangladesh, Rohingyas are now also present in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Thailand. It is estimated that nearly 40,000 Rohingyas have found their way to India from Myanmar through the rather porous Indo-Bangladesh border. Most are concentrated in the seven states of Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Assam, Jammu and Kashmir and Delhi. Among them, only 16,500 are registered with the UNHCR and have refugee status while most of them are unregistered and are considered illegal immigrants.

India, on the other hand, has branded all of them, irrespective of their refugee status, as illegal immigrants and Union State Minister for Home Affairs Kiren Rijiju told parliament last week that the central government had directed state authorities to identify and deport illegal immigrants including Rohingyas, who face persecution in Buddhist-majority Myanmar. Following this, there has been a fear amongst Rohingyas in India. Minister Rijiju told Reuters news agency, “They [UNHCR] are doing it, we can’t stop them from registering. But we are not signatory to the accord on refugees”. He added: “As far as we are concerned, they are all illegal immigrants. They have no basis to live here. Anybody who is an illegal migrant will be deported.” The United Nations’ top human rights body criticized the government plan to deport Rohingyas earlier this week.

India has tightened its security along the northeastern border to prevent the influx of Rohingyas from Bangladesh. The government fears illegal immigrants could be recruited by terrorists and such mass exodus of the Rohingyas from Myanmar can substantially increase the possibility of terror activities. When two Rohingya refugees filed a plea in the Indian Supreme Court against deportation, the government of India filed an affidavit claiming that allowing Rohingyas in India poses a national security threat, pointing out intelligence reports linking some Rohingyas to Pakistan-based terror groups and also added that the decision to allow or not to allow the refugees is best left to the executive.

Weighing the options

Nepal on the other hand is wary of the possible entry of Rohingyas and has tightened security points along the eastern border and a special police team has been mobilized to stop the Rohingyas from entering Nepal. It is estimated that more than 300 Rohingya Muslims live in a makeshift shelter at Kapan area in Kathmandu. Most of them came to Nepal after the 2012 violence in Myanmar between Rohingya Muslims and Rakhine Buddhist populations.

If the decision of the Indian Supreme Court goes against the Rohingyas, many of them may cross the porous India-Nepal border to avoid deportation from India. In such a case, Nepal must choose its steps carefully. On the one hand, Nepal has its own problems with the constitution, entrenched poverty and political stability, and on the other, it also needs to be considerate about the plight of the “stateless” Rohingyas . The search for permanent solution for these Rohingyas is still on and may take some time yet. As Desmond Tutu said, “Hope is being able to see that there is light despite all of the darkness”. So let us hope.

The author is a reporter with Nagarik daily

You May Like This

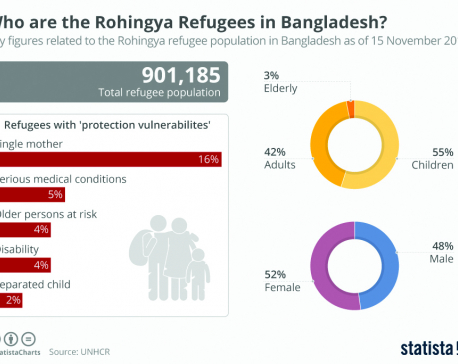

Infographics: Who are the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh?

There are at least 901 thousand Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Having fled what the UN has called a genocide in... Read More...

Murders leave Rohingya camps gripped by fear

BANGLADESH, Aug 17: A spate of bloody killings is fuelling unease in the Rohingya camps on the Bangladesh-Myanmar border, where... Read More...

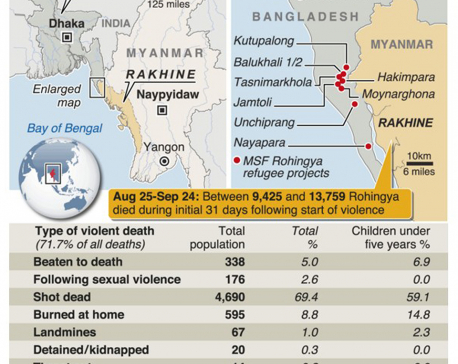

Infographics: Rohingya Muslims killed in Myanmar

At least 6,700 Rohingya Muslims, including 1,200 children, were killed in the first month of a Myanmar army crackdown on... Read More...

Just In

- Rain shocks: On the monsoon in 2024

- Govt receives 1,658 proposals for startup loans; Minimum of 50 points required for eligibility

- Unified Socialist leader Sodari appointed Sudurpaschim CM

- One Nepali dies in UAE flood

- Madhesh Province CM Yadav expands cabinet

- 12-hour OPD service at Damauli Hospital from Thursday

- Lawmaker Dr Sharma provides Rs 2 million to children's hospital

- BFIs' lending to private sector increases by only 4.3 percent to Rs 5.087 trillion in first eight months of current FY

Leave A Comment