OR

Though militaries have often proved adept at staging coups, from Egypt to Thailand to Myanmar, they have been far less effective in securing transitions to civilian rule

TEL AVIV – Eight years after the Arab Spring, dreams of democracy in the Arab world have been dashed by the harsh reality of autocracy, corruption, and military rule. Yet Algeria and Sudan, neither of which was swept up in the 2011 turmoil, are now trying their luck at challenging the often-surreptitious powers that be—what Algerian demonstrators back in 1988 dubbed le pouvoir. Will Arab democracy movements fare any better this time?

In Algeria, the government’s plans to reduce its robust subsidy program—a response to years of declining hydrocarbon revenues—triggered protests so potent that they drove the military to pressure President Abdelaziz Bouteflika to resign last month, after 20 years in power (six of which were spent incapacitated after a stroke). But this does not mean a fresh start for the country.

To be sure, following Bouteflika’s resignation, five of Algeria’s leading oligarchs were arrested, and the CEO of the state energy company was dismissed. This was followed by more high-profile arrests, including of Said Bouteflika, the ousted president’s brother and Algeria’s de facto leader, as well as former intelligence chiefs General Bachir Athmane Tartag and General Mohamed Mediène (better known as Toufik).

But, as badly as Algeria’s military, led by General Gaid Salah, wants citizens to believe that it is dismantling the cabal of well-connected cliques that form le pouvoir, the protesters remain convinced that this is just a smokescreen. Salah should be arresting himself, shout the masses, who continue to spill out onto the streets each week, in order to demand that le pouvoir truly be swept away, so that it cannot handpick Bouteflika’s successor.

Algerians know how resilient le pouvoir is. It was given this name during the 1988 Black October riots—an explosion of mass rage against a corrupt, autocratic one-party system controlled by the National Liberation Front (FLN). The government responded by ordering the security forces to crack down, resulting in some 500 deaths and more than 1,000 injured demonstrators.

The protests did drive President Chadli Bendjedid to promise to hold free elections for the first time in Algeria’s history, and political parties other than the FLN were legalized in 1989. But when the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) appeared poised to defeat the FLN two years later, the elections were canceled. The military took effective control of the government and banned the FIS, arresting thousands of its members. This triggered a brutal decade-long civil war that left more than 200,000 dead—and Algeria with a military-backed government led by Bouteflika.

Algeria’s experience up to this point foreshadowed the Arab Spring, during which le pouvoir’s survival instinct was on stark display. Syria’s pouvoir, led by Bashar al-Assad, has defended its business and tribal interests mercilessly, with the help of foreign actors that have a strategic interest in his political survival. None of them loses sleep over the more than half-million Syrians killed and millions more who have been displaced since 2011.

Toppling dictatorships

But there are also plenty of examples of Arab societies managing to topple secular dictatorships. Lacking a sufficiently large middle class or a strong liberal tradition, the people then democratically elect an Islamist party. Unable to accept that outcome, le pouvoir—in this case, led by the military, without its dictator-figurehead—takes action to restore secular strongman rule.

Though militaries have often proved adept at staging coups, from Egypt to Thailand to Myanmar, they have been far less effective in securing transitions to civilian rule. This is because the military has held power all along: while it may be happy to trade one figurehead for another, it has no real interest in upending the political and economic structures it commands.

Egypt’s experience exemplifies this pattern. After the 2011 ouster of Hosni Mubarak, Egyptians elected President Mohamed Morsi and his Muslim Brotherhood. By 2013, Morsi’s elected government was overthrown, and Morsi’s military-backed successor, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, has been in power ever since.

Last month, Sisi’s government held a sham constitutional referendum that extended his term from four years to six and lifted the two-term limit. With that, Sisi’s one-man rule and the supreme authority of the military—which controls at least 30 percent of the economy—was solidified, and whatever remained of democratic governance in Egypt was demolished.

This pattern could be set to repeat anew in Algeria, and Sudan may well be heading toward a similar fate. Like in Algeria, mass protests drove a cabal of army officers last month to topple President Omar al-Bashir, who had been in power for 30 years.

Following a few days of confusion among the military hierarchy, General Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman Burhan, the de facto head of state, announced that the army would take charge to “uproot” the military government and prosecute those, including Bashir, responsible for killing protesters. Power, he vowed, will be handed over to a civilian government within two years.

Case of Sudan

Given the historical precedents, it is not the most convincing promise. Yet Sudan has one factor on its side: whereas the Arab League behaves essentially as a regional club of autocracies, the African Union has limited tolerance for coups d’état—a preference that might partly explain the decline in military takeovers in Africa in recent years. The AU has now threatened Sudan’s new rulers with suspension from the group, unless they transfer power to a civilian authority.

Even if Sudan’s military leaders succumb to AU pressure, however, political stability is far from guaranteed. For decades, le pouvoir used oil revenues to buy relative public quiescence through massive subsidies. But those reserves were concentrated in the south, and were thus lost when South Sudan seceded in 2011. And now political stability is gone.

As in Algeria, however, the struggle for genuine change is hardly over. The demonstrators in both countries have fought for the opportunity to be governed by leaders with broad popular support. But, as they attempt to redeem the promise of the Arab Spring, le pouvoir will regroup, demonstrating once again that its resilience remains the biggest obstacle to reform in the Arab world.

Shlomo Ben-Ami, a former Israeli foreign minister, is Vice President of the Toledo International Center for Peace. He is the author of “Scars of War, Wounds of Peace: The Israeli-Arab Tragedy”

© 2019, Project Syndicate

www.project-syndicate.org

You May Like This

Reviving home remedies

Garlic has antibacterial, antivirus, antifungal, and antioxidant properties and nutrients. For this reason, garlic soup is used by many people... Read More...

Going electric

Nepal should aim for promoting electric vehicle technology. Strategic approach should be adopted to formulate policies to encourage people to... Read More...

Reimagining leadership

Transitional justice process has not come to a meaningful end because conflict victims were not placed at the center ... Read More...

Just In

- Teachers’ union challenges Education Minister Shrestha's policy on political affiliation

- Nepal sets target of 120 runs for UAE in ACC Premier Cup

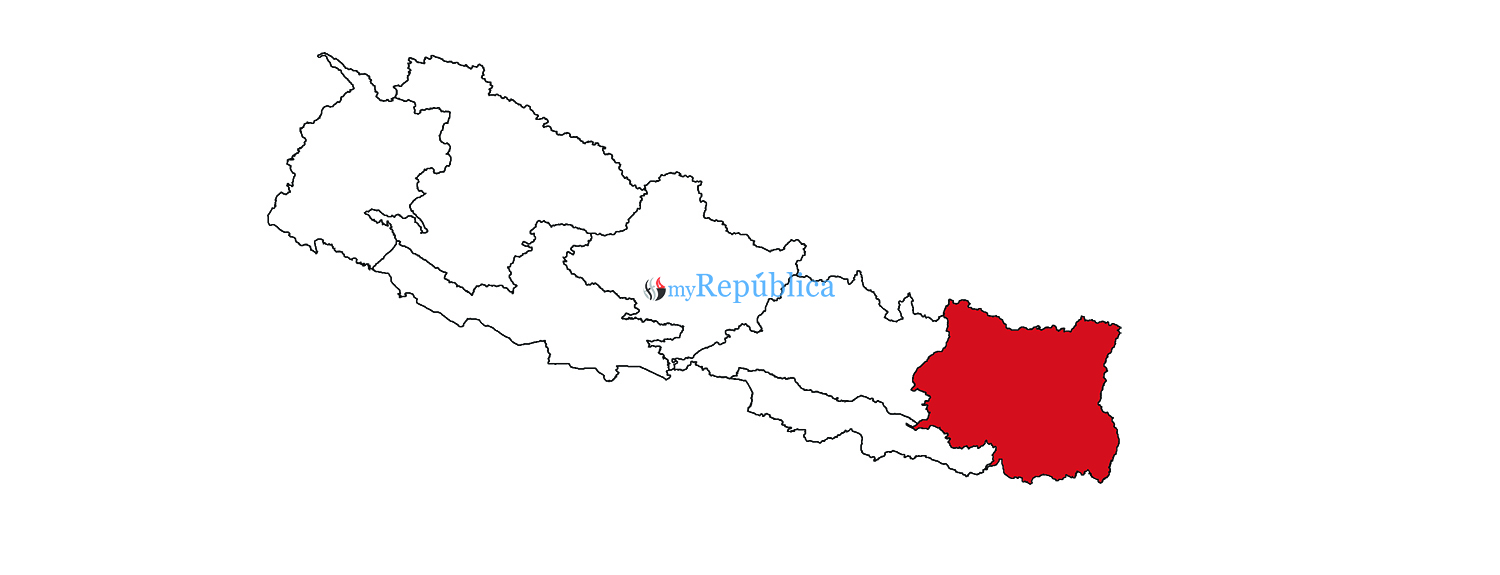

- Discussion on resolution proposed by CPN-UML and Maoist Center begins in Koshi Provincial Assembly

- RBB invites applications for CEO, applications to be submitted within 21 days

- Telephone service restored in Bhotkhola after a week

- Chemical fertilizers imported from China being transported to Kathmandu

- Man dies in motorcycle accident in Dhanusha

- Nepal face early setback as four wickets fall in powerplay against UAE

Leave A Comment