OR

The little tricks and technologies we used to manage through the darkest days of load-shedding has set us up for the future, if only we had the courage to look forward

The only thing Nepal got out of its experiences with years of load-shedding (forced grid blackouts) was a national hero who showed us that it was actually possible for the power utility to do exactly what it was supposed to do in the first place—provide reliable electricity.

Save for the legacy of Kulman Ghising, Managing Director of Nepal Electricity Authority, the state-owned national monopoly power utility, Nepal got and learned absolutely nothing out of the load-shedding crisis.

For several years up to the second half of 2016, Nepal endured long hours of forced grid blackouts, popularly called load-shedding. At its worst during the winter months, Kathmandu, for example, faced as many as 18 hours of power cuts every day.

The prolonged power crisis was the result of severe shortages in electricity supply, though we have learned recently that dedicated power supply to industries brokered through sweetheart deals may have worsened the problem. And then Kulman arrived, magically kept the lights on and became a national hero.

Today, the situation has changed. Electricity supply is now highly reliable in most parts of the country. Electrification is growing rapidly with many new off-grid areas being connected to the national grid. Electricity generation is increasing, with several hundred mega-watts (MW) projected to come on-line.

So, what did we learn from the experiences of the load shedding years?

Adapting to crisis

Years of load-shedding was an important era that symbolized the failures of government and hope in Nepal. But as severe as the crisis was, it also spawned many ways we learned to adapt to the crisis.

An industry of solar and battery companies emerged. Solar, inverter and batteries became a household name. Many people installed these—sometimes just an inverter and battery—to provide some relief against load-shedding. The government responded by banning the use of inverters that could charge batteries using grid power. These inverters, it was believed, would draw power from the grid and, in aggregate, exacerbate the extent of load-shedding. That ban remains in effect, though it was never a ban that was genuinely enforced.

With the end of load-shedding, things have changed. Many companies that offered solar-inverter-batteries or just inverter-batteries have gone out of business.

The humble batteries and inverters that had so faithfully powered our homes and office during the long hours of load-shedding have become the villains of sorts. When asked if ending load-shedding simply meant sending all our foreign reserves to India because we were importing so much electricity, Ghising calmly replied that the higher electricity imports were being offset by the dramatic reductions in inverter and battery imports.

So, what did we learn from our experiences from load shedding? Nothing. As a country we learned only to adapt to the greatest electricity crisis of our history. Load-shedding was an exhibition of Nepal’s endurance against hardship, nothing more.

Missed opportunity

Shortly after the new government took over and as load-shedding appeared to be come to an end, the ministry of energy released its white paper documenting its strategy for the sector. The strategy contained all the pieces you might have expected: increase supply, reduce loses, increase transmission, encourage cross-border trade, bring reforms and seek to create markets. It introduced new concepts, at least new to Nepal, such as energy efficiency and conservation.

But for all the things it promised, the ministry’s white paper failed to recognize how load-shedding could have been the turning point for Nepal’s energy future.

For many of us, the response to load-shedding was the humble battery and inverter. We allowed the inverter to charge the battery when the grid was on and then used the battery for electricity during load shedding. To increase battery charging, many also supplemented the system with solar to charge the batteries.

This was a simple, yet effective solution. It allowed us to become producers, consumers and managers of our own power. As it turned out, in the rest of the world, this technology was also driving similar changes: People were becoming their own producers, consumers and managers of power.

In Nepal, the government’s enduring ban on inverter is a bit like banning emails out of concern that the miserably lousy government’s postal mail would otherwise not be used and therefore, become of even worse quality. That ban—though perhaps forgotten because no was really interested in enforcing it—is a powerful symbol of a government that has failed to look at the future in planning for the future.

Nepal’s 21st century challenges needs 21st century solutions. We cannot imagine a future by only looking back through the rear-view mirror.

What we should have learned

Today, the most radical solutions that are transforming the energy sector are based exactly on what we were attempting to do to manage through the darkest days of load-shedding. We were using the technology and resources available at the time to be our own producers of energy while simultaneously trying to manage our energy consumption.

Remember the days when we woke up at three or four in the morning to iron our clothes or run the water pump. Today’s energy transformations are doing exactly what we so painfully did during load shedding: Providing consumers with technology and solutions that allows them to choose when and how they want to produce, consume and manage their energy use (just without having to get up at three or four in the morning).

Today’s energy transformations are less about the declining cost of solar or wind. For the most part, those product costs appeared to have slowed down though important technical innovations continue to emerge. The focus has shifted to efficient methods for energy production and its use right in the place where you need it. Sharp declines in the cost of energy storage (battery), digital technologies and automation are enabling this transition.

Remember the handy tricks we learned during the load-shedding to keep our inverters from not beeping (overloading or running out of battery): Don’t switch this light with that; if you turn on the TV don’t turn on the fan; if you switch on the micro-wave, everything else must be turned off.

Today’s energy transformations are doing exactly that: The combination of automation, digitally connected appliances and smart control systems (like new generation inverters) are enabling consumers to manage their energy consumption seamlessly and automatically.

In the darkest days of load shedding we did all these things to manage—little tricks adapting whatever was available at the time. If at that time we survived 18 hours of load shedding with lower electricity imports from India and without the aid of new technologies, imagine what we could do with all the new technologies available today.

The government claims it will build 15,000 MW of new power plants. Every new energy minister, it seems, comes to office, adds 5,000 to that number and announces yet another “bold” plan. But do we really need all that centralized generation capacity if we could take charge of what we produce and consume on our own or through small communities collaborating with each other?

We all managed and overcame the load-shedding crisis. Now, we must find the courage to seize the future.

Bishal_thapa@hotmail.com

You May Like This

Reviving home remedies

Garlic has antibacterial, antivirus, antifungal, and antioxidant properties and nutrients. For this reason, garlic soup is used by many people... Read More...

Going electric

Nepal should aim for promoting electric vehicle technology. Strategic approach should be adopted to formulate policies to encourage people to... Read More...

Reimagining leadership

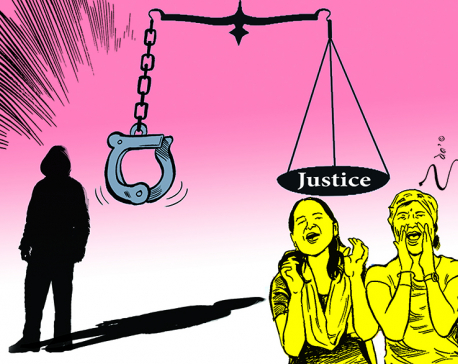

Transitional justice process has not come to a meaningful end because conflict victims were not placed at the center ... Read More...

Just In

- MoHP cautions docs working in govt hospitals not to work in private ones

- Over 400,000 tourists visited Mustang by road last year

- 19 hydropower projects to be showcased at investment summit

- Global oil and gold prices surge as Israel retaliates against Iran

- Sajha Yatayat cancels CEO appointment process for lack of candidates

- Govt padlocks Nepal Scouts’ property illegally occupied by NC lawmaker Deepak Khadka

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment