OR

Som P Pudasaini

The author was UNFPA Representative for Sri Lanka & Country Director for the Maldives.som.pudasaini@gmail.com

The war of words between the two rising global stars, nuclear powers and Asian giants continues to be a matter of great concern for Nepal

The bitterness caused by the 73-day face-off between the Indian and the Chinese troops in the Doklam plateau ended on August 28, with the India External Affairs Ministry’s announcement that New Delhi and Beijing had decided on “expeditious disengagement” of their border troops. This paved the way for a smooth ninth BRICS Summit and the bilateral meet on September 5 between the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Chinese President Xi Jinping on its sidelines in Xiamen in Southern China. After their meeting Indian Foreign Secretary S. Jaishankar said Xi and Modi felt that peace and tranquility in the border areas is a pre-requisite for ties to move forward. Both sides agreed “defense personnel must maintain strong contacts to ensure a situation like what happened recently” does not recur. According to Xinhua Xi also told Modi that the two countries should pursue “healthy, stable bilateral ties”.

However, the war of words continues to rumble in Nepal’s neighborhood. On September 6, just a day after Modi-Xi bilateral chat, Indian Army Chief Bipin Rawat declared India must be prepared for a potential “two-front war”. He stressed that “as far as our northern adversary is concerned, flexing of muscles has started” and accused China of “testing our limits”. Concerning its western neighbor he said the situation with China could gradually “snowball into a larger conflict that Pakistan could possibly exploit”.

In response, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang asked if Rawat’s remarks were “his own or reflect the Indian government’s stance”; even the Indian media considered his remarks “shocking”. China and India were “most important neighbor as well as the two biggest developing countries” and “the two nations shall together safeguard regional peace” Geng added. In its harsh editorial the Chinese Global Times on September 8 accused Rawat as a “big mouth that could ignite the hostile atmosphere between Beijing and New Delhi” and it reflected the “arrogance probably prevailing in the Indian army”.

The frenimies?

On the other hand, Brahma Chellaney, Professor of Strategic Studies at the New Delhi’s Center for Policy Research, emphasized that the “People’s Liberation Army sees itself as the ultimate arbiter of Chinese nationalism” and its chief, General Fang Fenghui, was “an obstacle to clinching” the Doklam pullout deal with India. Fang’s firing and changes in the PLA leadership highlight “Xi is still working to bring the military fully under his control” he added.

Consequently, the necessity of “peace and stability” in the border area and “stable bilateral ties” alluded by Xi and Modi may be a constructive dream that will continue to test the will and commitment of the two leaders for sustained peace in South Asia. Experts generally agree that it is hard to see India and China ever becoming close political friends. But the key geopolitical concern is: can they not be “violent rivals”, for their own benefit and that of South Asia and beyond?

In the context of the on-going Indo-China rumbling, the question of whether Modi or Xi blinked first continues to gain currency in the political and intellectual circles as it has long-term geopolitical consequences. Modi went to China with an “enhanced stature and stronger leadership credentials than Xi,” according to Mohan Malik, a professor at the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies at Honolulu. The BRICS visit and bilateral meeting came after “India’s refusal to join Xi’s Belt and Road Forum in May and decision to stare down the PLA despite daily threats and belligerent rhetoric,” he said.

However, other experts believe Modi had to bite the bullet first. India was pushed to withdraw troops and issue the “expeditious disengagement” announcement on August 28, while China continued to harp on its sovereignty and right to maintain military vigil in the Doklam area. Also, Modi had to refrain from raising any issue about the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which happens to be a showcase project for China’s Belt and Road Initiative. China didn’t want India to raise the issue at a time when CPEC has triggered some “heart burning” in the Pakistani business community and the country is politically fluid in the aftermath of Nawaz Shariff’s resignation resulting from its Supreme Court verdict against him.

Pak in middle

On the other hand, the BRICS declaration bracketed Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed with global terror groups such as Islamic State and al-Qaeda. It was a surprise Chinese acquiescence, marking a significant diplomatic win for India. While Pakistan remains its all-weather friend, a growing Chinese interest in regional stability and its desire to appease India may have encouraged China to stand against Pakistan-based terror groups. Obviously, China is also concerned about Islamist influence “spilling over” into Xinjiang region from Pakistan and Afghanistan. It also blends well with the current US policy in which it had warned Pakistan that it could cut military aid if the country doesn’t do more to tackle terror sanctuaries on the Pakistani side of the Afghan border.

While this appears to be a calculated move by the top Chinese leadership, Hu Shisheng, the Director of the Institute of South and Southeast Asian and Oceania Studies at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, thinks it posed the “biggest challenge” in the Sino-Pak relations since the 1960s” and was “really a big mistake, which the Chinese government will feel in the coming years”.

In response to the BRICS declaration, Pakistan Defense Minister Khurram Dastagir Khan flatly denied any existence of terrorist “safe haven” in his country. The Foreign Office spokesperson stressed Pakistan was “seriously concerned” about the threat posed by terrorism in South Asia. And he added that groups based in the region, including Afghanistan, “have been responsible for extreme acts of violence against Pakistani people”. Xi may also have considered two more points while supporting broader anti-terrorism BRICS declaration: inclusion of Pakistani terror groups and trying to make Xi-Modi bilateral meet as productive as possible.

Troublesome triad

Beijing was deeply concerned about India agreeing to a tacit India-US-Japan arrangement during the recent New Delhi visit by the Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe. Beijing continues to have a territorial dispute with Japan and is its key rival in Asia-Pacific in both military and economic terms. Second, India had approached Russia to convince China on Doklam standoff and to get it to drop its opposition to India’s Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) membership. Given that Russia has been India’s important strategic partner and given the rising China-Russia multi-faceted collaboration, India’s use of Moscow to convince Beijing and Beijing’s desire to prevent rising Indo-Japan closeness are important considerations for both Indo-China relations and South Asian geopolitics.

Consequently, the war of words and political rumbling between the two rising global stars, nuclear powers and Asian giants continues to be a matter of great concern for Nepal, South Asia and rest of the world. Direct or indirect entanglement of the third Asian nuclear power, China’s all-weather friend and perpetual Indian antagonist, Pakistan, makes the situation riskier. Japan and US’s complicated dynamics with China and growing camaraderie with India may add further fuel to the fire if not handled judiciously.

The author is former UNFPA Representative for Sri Lanka and Yemen and Country Director for the Maldives

som.pudasaini@gmail.com

You May Like This

Exploring opportunities and Challenges of Increasing Online Transactions in Nepal

Recently, I embarked on an errand for my parents. Upon completing my purchases, I proceeded to the checkout. The cashier,... Read More...

Why Federalism has Become Risky for Nepalese Democracy

The question arises, do federal or unitary systems promote better social, political and economic outcomes? Within three broad policy areas—political... Read More...

Nepal's Forests in Flames: Echoes of Urgency and Hopeful Solutions

With the onset of the dry season, Nepal's forests undergo a transition from carbon sinks to carbon sources, emitting significant... Read More...

Just In

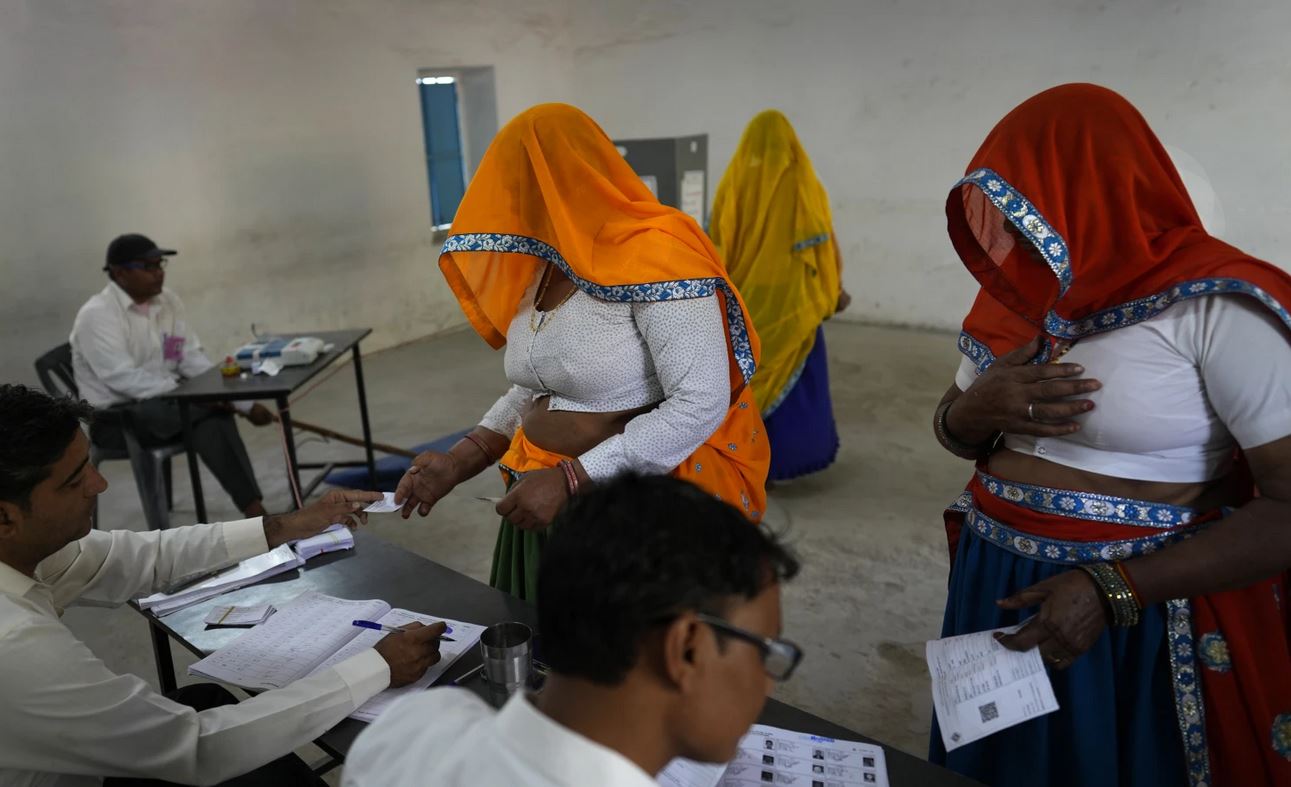

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

- 352 climbers obtain permits to ascend Mount Everest this season

- 16 candidates shortlisted for CEO position at Nepal Tourism Board

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment