OR

More from Author

Diversity is strength only if the state promotes a policy of equality and justice. Inequalities, oppression and marginalization lead to instability and conflict

The pain of marginalization is deeply excruciating. Especially, if one is undermined, disrespected or rejected because of the color of their skin, caste, ethnic identity and the mother tongue, none of which is their personal choice, the awareness of being excluded for these reasons fuels discontent and motivations for resistance. The main agenda of Nepal’s social movements—such as Indigenous Movement, Women’s Movement, Dalit Movement, Tharu Movement and Madhes Movement among others—is concerned with the politics of marginalization. Social movements also serve as educational institutions that create an opportunity for the grassroots to learn about their social and political locations in the society where they live in. They become increasingly aware of how power and resources are distributed and whose cultural capital is legitimized through formal state institutions and how existing social, political and economic structures reproduce existing unequal power relationships between diverse cultural communities.

Most importantly, activists learn how to articulate their agenda and express their demands. Activism also teaches important movement skills such as mass mobilization, communication and resistance techniques.

Education as a tool

Structural inequalities are maintained by formal policies or dominant cultural norms that privilege one group over the other. These are manifested in terms of unequal access to education, health care and livelihood opportunities based on people’s cultural, social and regional locations. For example, Nepali as the formal language of instruction at school structurally limits the learning potential of children from non-native Nepali speaking backgrounds. In Nepal, historically, caste-based roles have been reinforced through formal educational processes. Teaching, learning and knowledge production has been socially understood as the portfolio of high caste groups; and through a formal curriculum and educational practices, culturally privileged groups have dominated the knowledge domains. As a result, the majority of leadership positions in political parties, civil society organizations, academic institutions, policy circles, bureaucracy and the judiciary are monopolized by high caste groups.

Marginalized social groups suffer from the historical process of neglect and erosion of their social and cultural capital. They struggle to stay motivated for changing the conditions of marginalization and their social network is usually incapable of cultivating high aspirations. Their community gradually loses role models that provide a sense of alternatives and new avenues for change. A Madhesi can tell how they are treated differently in their own country; a woman can tell how she feels oppressed by a male-dominated society; a black person can tell how they are racially discriminated against; only a Dalit can truly describe the feeling of being treated as untouchable. Social movements provide marginalized communities with critical consciousness and motivation to struggle for a change.

Of course, there is a counter-argument that not all who are in the leadership represent the high caste privileged groups; there are high caste people who may be as poor and disfranchised as the socially marginalized and most importantly, for example, Brahmins do not prevent other castes from succeeding educationally or competing for positions of power. So, why antagonize people against the ethnic and caste-based identities? This is certainly true at individual levels. But the exclusionary nature of social and political structures creates such conditions that it becomes difficult for individuals from marginalized communities to succeed and secure competitive advantages within the existing political system. The privileged ethnic and social groups do not experience discrimination in the same way the marginal communities do, and their experiences of discrimination are rather collectivized along their caste or ethnic identities.

Structural discrimination

There are certainly resilient individuals or outliers who cut through structural barriers and succeed despite unfavorable conditions. If we make a rule that everyone who intends to appear for a civil service exam should go to Kathmandu, a qualified person from a poor family in Bajura or Saptari is less likely to travel to the capital. An individual from the marginal community faces additional barriers such as bureaucratic hostilities and maltreatment because of the way they look or speak the language. Women from these communities are further disadvantaged culturally and socially. Hence, generally speaking, people from minority culture and linguistic communities feel less confident about securing a place within the dominant community that enjoys power and privileges.

Social and cultural expectations also matter enormously. I remember my own schooling in the 1980s during the dusk of the Panchayat era. Despite my school being located in the neighborhood of a Dalit community, none of my classmates from the Dalit community completed education beyond the fifth grade. When I stood second in the class in one of my term exams, the head teacher who happened to be our relative, visited our home to complain about it to my father. I remember one of my next-door friends from the Magar caste being praised for securing a pass mark and I was ridiculed for not achieving a distinction. Very few of us succeeded in the SLC exam but those who did were by far a majority, if not all, of Brahmin and Chhetri boys. As a Brahmin child, it was unacceptable to underperform while, failures of Dalit and Janajati children in education was a norm. The school system implicitly promoted a culture of educational expectations along the caste lines which benefitted high caste children.

Fostering inequality

These deeply internalized unjust practices in Nepal have led to the creation of an unequal society where some ethnic, regional and caste communities have been systematically marginalized, providing a space for social justice struggles. Social movements that are rooted in these problems, particularly since the 1990s, have sensitized the politics of identity and marginalization as a means to secure dignified political representation and formal recognition in the character of national identity. The main agenda is equity and social justice. Social movements, in this process, have contributed to building confidence among the marginalized populations to be able to claim their rights. The gains of the movements are beyond what their leaders have achieved in politics, nor should they be judged against the character of their leaders who might be equally corrupt, manipulative and demoralizing as their traditionally dominant counterparts. Movement gains should also be gauged in terms of social consciousness and community’s enhanced ability to claim their rights as equal citizens of the country. During my recent fieldwork in Madhes, when I asked a Madhesi youth about what they had achieved through Madhes movement, he replied: “Brother, I can now speak in Maithili with my friend from Janakpur at the heart of Kathmandu in the crowd of Pahadi people, without fear and being ashamed.”

Let us accept that so far, we have been a nation of rich cultural diversity but with a political dominance of hill high castes, representing one culture, one language and one religion. Diversity is a strength, only if the state promotes a policy of equality and justice through which diverse cultural groups feel recognized and represented equitably. Inequalities, oppression and marginalization in a diverse society lead to political instability and violent conflict. Political uprisings may be momentary but social movements always remain vibrant within the grassroots and, as they stem from people’s ongoing grievances, they are the ultimate defense of struggles for peace with social justice.

The author is an Associate Professor in Education and International Development at the University College London

t.pherali@ucl.ac.uk

You May Like This

Rethinking business

We need a shift in paradigm from business is politics and politics is business to business in nature and vice... Read More...

Women on top in democracies

In today’s world, men continue to hold disproportionate power. But, judging by the fast-growing number of women on the political stage,... Read More...

Spain’s political paralysis

Many in Madrid say that Spanish politics is becoming Italian, only without the Italians’ feats of political gymnastics ... Read More...

Just In

- Rainbow tourism int'l conference kicks off

- Over 200,000 devotees throng Maha Kumbha Mela at Barahakshetra

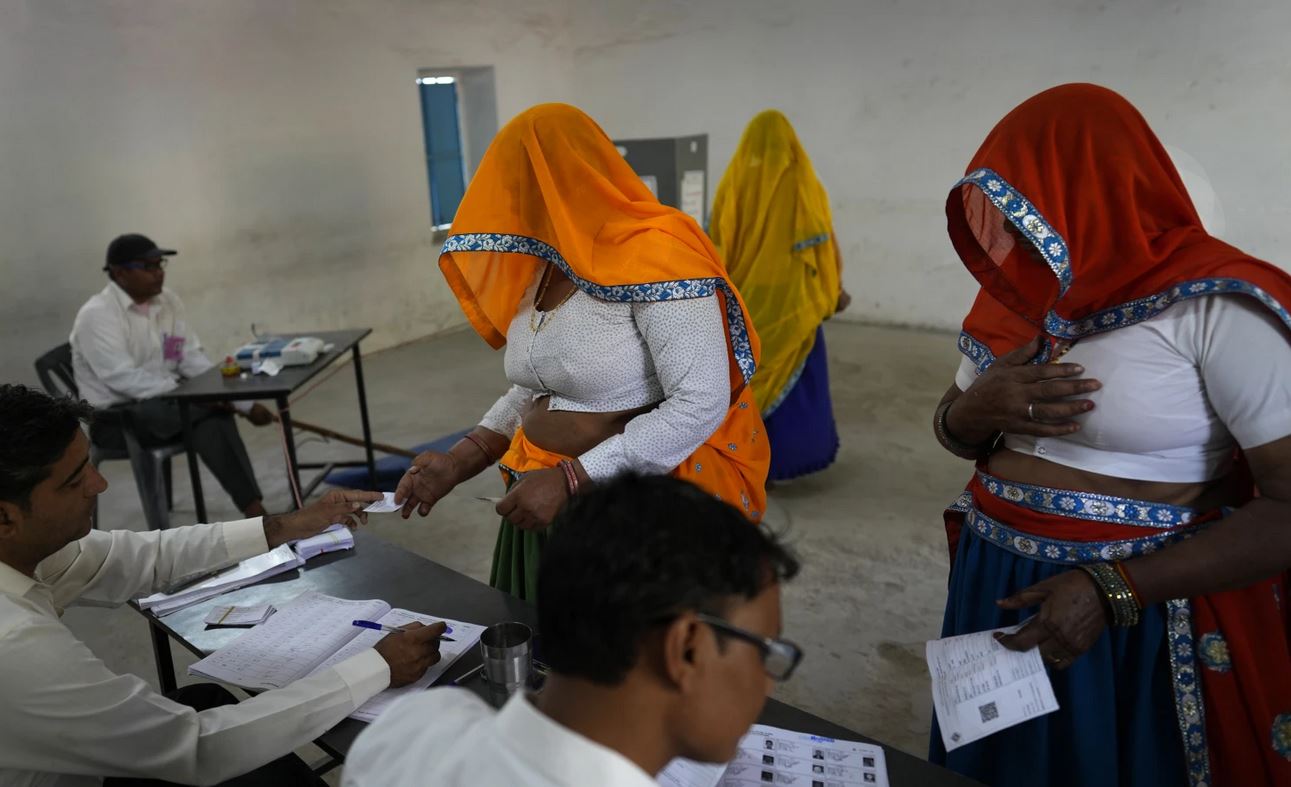

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment