OR

Hungary’s fights for impunity

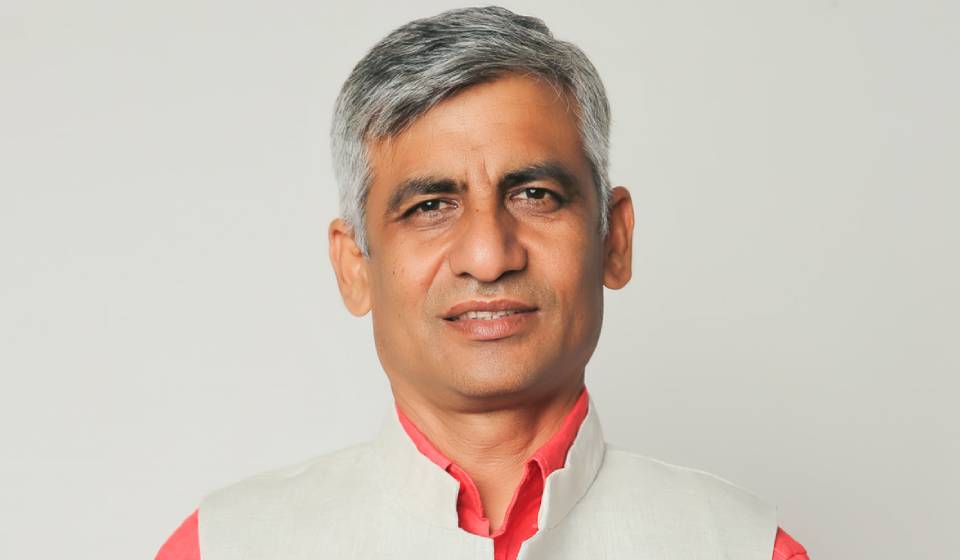

Published On: June 29, 2019 01:05 AM NPT By: Bálint Magyar/Bálint Madlovics

More from Author

Orbán’s anti-EU stance does not reflect a different vision of Europe. Rather, it stems from his need to insulate himself and his clan from law enforcement

BUDAPEST – Hungary has become a post-communist mafia state. It is led not by a party but by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s political-economic clan, which treats society as its private domain while formally maintaining a democratic façade. The Hungarian state’s actions are not impersonal but rather discretionary, aimed at taking down the clan’s opponents and redistributing wealth and assets to loyalists. Orbán uses the bloodless means of bureaucratic coercion, yet still acts illegally: corruption and politically selective law enforcement are central to his system.

The mafia-like character of Orbán’s regime explains his behavior. A criminal organization, whether private or public, has three crucial needs: sources of money, the ability to launder it, and impunity for its members. The last requires neutralizing law enforcement, which Orbán is finding much harder to do at the European Union level than at home.

Over the past decade, Hungary’s mafia state has mastered the first two imperatives—looting and laundering money. The Orbán clan’s oligarchs receive around 90 percent of their total revenue from EU-funded public procurement projects. According to the Corruption Research Center Budapest, the contracts for these projects are 1.7-10 times overpriced—which points to noncompetitive bidding processes and high corruption risk.

Autocratic regimes elsewhere provide additional funding. This includes a €10 billion ($11.2 billion) loan from Russia to finance the replacement of the nuclear power plant in Paks, $3 billion from China to build a high-speed rail link, and military industry cooperation with Turkey. Each of these deals, ultimately paid for by Hungarian taxpayers, adds to the balance sheet of Orbán and his oligarchs. They also make Orbán a blackmailable vassal of Eastern autocrats, and thus a Trojan horse capable of undermining further EU integration and thwarting Europe’s global political ambitions.

Because Orbán’s cronies are involved in legal businesses like construction and media, they can launder illegally gained public funds simply by paying themselves huge dividends. Orbán’s father, his son-in-law, and his economic front man Lőrinc Mészáros—a former gas fitter who has become Hungary’s richest man within a matter of years from public procurement projects—received a combined $170 million in dividends in 2018 alone.

The need for impunity, meanwhile, explains Orbán’s anti-EU stance. The mafia state has already ensured its domestic impunity by taking over the police, prosecutor’s office, and Constitutional Court, none of which will now authorize investigations into the Orbán clan’s power and wealth. But the Hungarian regime needs international impunity as well. This is why Orbán has launched a “national freedom fight,” opposes Hungary’s accession to the European Public Prosecutor’s Office, and complains of an “infringement of sovereignty” whenever outsiders raise issues of corruption. His nationalist stance is nothing more than a fig leaf for a criminal organization’s naked demand for impunity: to be left alone to steal from Western taxpayers, free of EU supervision.

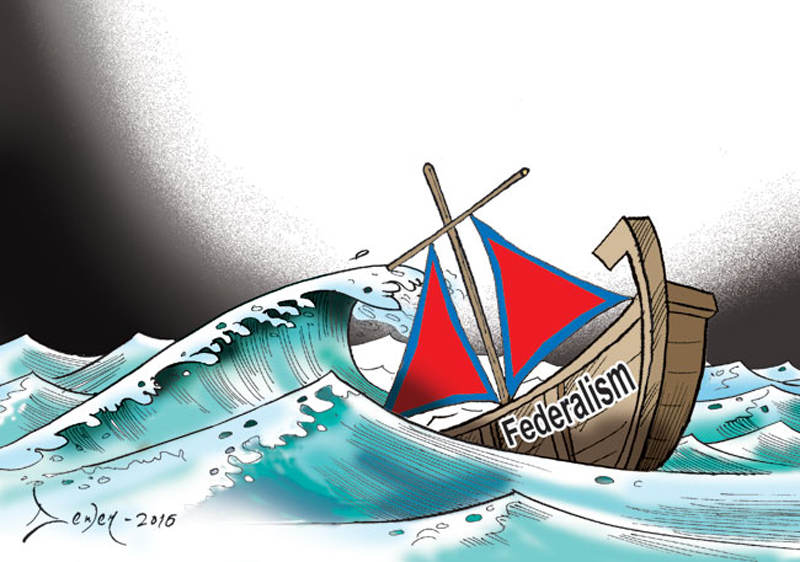

Orbán has tried to secure impunity by exploiting one of the EU’s structural flaws: member states’ right to exercise national vetoes over the bloc’s decision-making. One can see a parallel between today’s EU and seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Poland, where the nobility’s free veto (liberum veto) led twice to the mutilation—and eventually to the division among neighboring powers—of what was then Europe’s largest empire. Orbán hopes that forming blackmail alliances with other autocratically minded EU governments will stop further European integration and ward off any possible EU attacks on his mafia state.

Orbán initially tried to create such an alliance with the three other Visegrád countries. Yet this proved unsuccessful. Slovakia recently elected a liberal, pro-EU president, while the Czech Republic has experienced mass demonstrations against far lower levels of corruption than in Hungary. Finally, although Poland’s de facto leader Jarosław Kaczyński shares Orbán’s autocratic and anti-EU tendencies, he is motivated by ideology, not wealth. Unlike Orbán, Kaczyński is not building a political-economic clan to rob his own country.

Having failed to form a Central European blackmail alliance, Orbán instead turned to other populist forces across the EU. The “Europe of nations” initiative provided an ideal vehicle for linking the nationalism of West European populists and the Hungarian mafia state’s need for impunity. Orbán tried to boost his standing among these forces by exploiting the EU’s migration crisis, and, more generally, by aligning his interests with those of his autocratic paymasters in the East.

But this populist alliance has also failed to take off, as the results of last month’s European Parliament election showed. Throughout Europe, liberal and green parties gained ground, and populists could not break through.

The EU’s only mafia state is ever more unscrupulous in using coercion at home, helping Orbán’s ruling coalition to secure 52 percent of the national vote in the European Parliament election. But internationally, the Hungarian regime now has little room left to maneuver. EU citizens have realized that only through further integration can the Union grow from a mere economic power into a global political actor on par with the United States and China. Moreover, the EU is taking steps to combat corruption within member states by trying to link its funding to rule-of-law criteria.

Orbán’s anti-EU stance does not reflect a different vision of Europe. Rather, it stems from his need to insulate himself and his clan from law enforcement. He acts like a criminal—and should be dealt with as such.

Bálint Magyar, a former Hungarian minister of education, is a fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study at the Central European University in Budapest. Bálint Madlovics is a fellow at the Financial Research Institute in Budapest

© 2019, Project Syndicate

www.project-syndicate.org

You May Like This

Cudgelling corruption

During the multiparty democratic dispensation, corruption got democratized. In federal democratic republic Nepal, corruption seems to have become institutionalized... Read More...

Defamation case a planned attempt to discourage media from exposing corruption: FNJ

KATHMANDU, Sept 3: The Federation of Nepali Journalists (FNJ) has denounced the defamation case filed against Nagarik Daily by Nepal Oil... Read More...

Impeachment of Karki is a must for corruption free Nepal: Lawmaker Adhikari (with video)

KATHMANDU, Oct 25: CPN-UML lawmaker Rabindra Adhikari has said the impeachment motion tabled in the Parliament is not the issue... Read More...

Just In

- Dalit sexual and gender minorities lack representation within their own communities and groups

- Nagdhunga-Sisnekhola tunnel breakthrough: Beginning of a new era in Nepal’s development endeavors

- Altitude sickness deaths increasing in Mustang

- Weather forecast bulletin to cover predictions for a week

- Border checkpoints in Sudurpaschim Province to remain closed till Friday evening

- Gandaki Province Assembly session summoned

- CM Karki to Speaker: Resolution motion for vote of confidence unconstitutional

- EC reminds all for compliance with Election CoC

Leave A Comment