OR

Beyond borders

Biswas Baral

Biswas Baral has been associated with Republica national daily as a journalist since 2011. He oversees the op-ed pages of Republica and writes and reports on Nepal's foreign affairs. He is a regular contributor to The Wire (India).biswas.baral@myrepublica.com

More from Author

It is said that a country’s foreign policy is only an extension of its domestic polity. This makes sense. Nepal has struggled for a proper foreign policy orientation as the political transition that started with the overthrow of monarchy in 2006 drags on and on. The promulgation of new constitution on September 20th, 2015, was supposed to mark an end of this protracted transition, so that the country could finally embark on the ultimate goal of economic empowerment of its citizens. It wasn’t meant to be. The new constitution, instead of helping the country move to a new phase of development, has given rise to new cleavages—some real, some manufactured—in the society.

No wonder the new constitution is also muddled about the country’s foreign policy outlook. Nepal will, according to the constitution, “conduct an independent foreign policy based on the Charter of the United Nations, non-alignment, principles of Panchsheel, international law and the norms of world peace”. It is not clear how outdated notions like “non-alignment” and “Panchsheel” coined at the height of the Cold War are any more relevant. While these old ideas are included, economic diplomacy, which is the basis of modern international relations, does not find a mention in the new constitution.

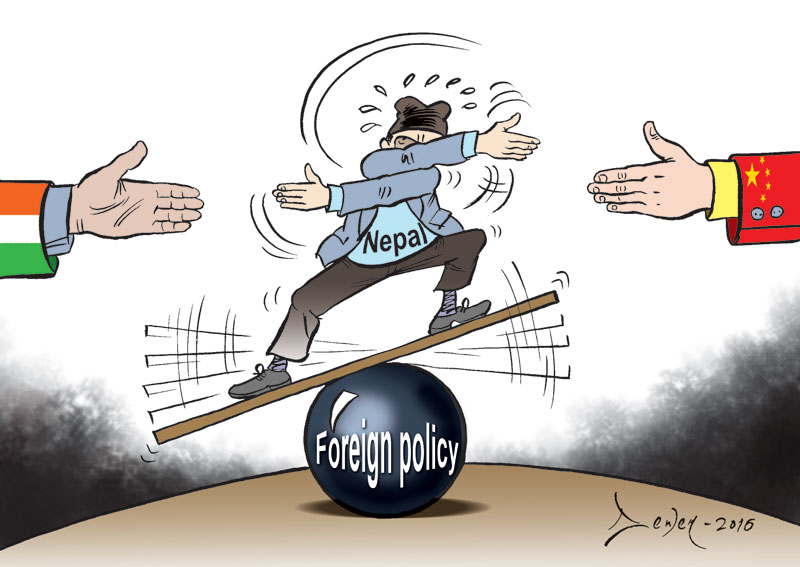

Ever since Prithvi Narayan Shah, the founder of modern Nepal, set up the Jaisi Kotha in 1769 to handle Nepal’s foreign relations, our rulers have been preoccupied with the notion of maintaining a proper balance between India and China so that the ‘yam’ between these two giant boulders was not crushed. His writings suggest Shah was a keen geopolitical strategist, well aware of the risks of tilting either towards India or China. How relevant is his characterization of Nepal as a precariously placed yam today?

I think it’s still a useful characterization. But it has its limits. He made the analogy at a time of rapid conquest of the Indian subcontinent by the British. At the pace they were going, that the British would sooner or later conquer Nepal must have seemed inevitable to Shah. That is why his emphasis on China as a counterweight against British invaders in India.

But nor was he inclined to trust the Chinese emperor as the court in Beijing had always treated Nepal as a vassal state from which it extracted annual tributes. Thus only by judiciously balancing the influence of India and China could Nepal, in Shah’s reckoning, continue to maintain its sovereign existence.

Insecure India

Geopolitics doesn’t change, nor do your neighbors. The central contradiction in Nepali foreign policy formulation continues to be how to maintain the age-old balance: not to in any way jeopardize the benefits accruing from our extensive ties with India while also looking to benefit from China’s rapid rise. In many ways, these are contradictory goals. India has been almost paranoid about protecting its ‘sphere of influence’ in the buffer states of Bhutan and Nepal following its humiliating loss to China in 1962. India has thus repeatedly rebuffed suggestions for trilateral cooperation between India, China and Nepal. India is loath to invite China into its old ‘backyard’.

This old fear of China, in my view, is unwarranted. If India wants to be acknowledged as the undisputed leader in South Asia—which is apparently one of Narendra Modi’s foreign policy goals—it must first junk obsolete ideas like maintaining spheres of influence. It must rather be ready to work in the interest of smaller countries in the region—even if it entails working with China. Leaders are comfortable in their own skin and they lead by example. But India, by resorting to highly coercive measures like an economic embargo to impose its diktats in small countries like Nepal, gives off an unmistakable whiff of a rising but an insecure power. If India is uncomfortable about its place in the region, how can it credibly stake its claim at the global high-table?

But forget India for a bit. Let us first ask ourselves: What is it that we want form India? The 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship is now up for renegotiation. We here in Nepal get to hear a lot about the ‘unequal’ treaty and how it should be summarily ditched.

But what kind of a treaty do we want in its place? Do we want greater regulation of the Indo-Nepal border? Do we want to do away with the provision that allows millions of Nepalis to enjoy the right to travel and work freely in India? Before we make demands of India, have we here in Nepal properly calculated the costs and benefits of redefining our terms of engagement?

Divided Nepal

Nepal’s political problems are, unfortunately, being reflected in our foreign policy as well. The Pahadi constituencies would apparently like nothing more than resetting the equation with India and signing a new treaty based on complete equality between the two countries. Most Madheshis, meanwhile, given their extensive ties with people just across the border, seem perfectly happy with the current provisions.

Could it be that the idea of Nepal for common Madheshis is completely different to the idea of Nepal for common Pahadis, a difference which also reflect on how they view India? What if these two ideals of Nepal are incompatible? More worryingly, what if there are competing imaginations of Nepal for Madheshis, Khas-Arya, Dalits, Janajatis, Tharus, Muslims and other ethnic groups? Can the Nepali polity adequately address the dreams and aspirations of people from all these diverse communities?

Some might baulk at such ethnic characterization of Nepali polity. After all, prolonged instability in Nepal can as easily be attributed to the tendency of our political parties to monopolize and misuse power, thereby also complicating foreign policy formulation.

Yet we cannot run away from the fact that in ethnically diverse but poor democracies—Nepal, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kenya, the Balkan states, wherever you care to look really—ethnicity continues to be the most effective tool of political mobilization. This is not to endorse ethnicity-based politics but only to acknowledge its indisputable existence.

In Nepal’s case, unless the country can come up with a working consensus of what it means to be a Nepali and with new symbols to emotionally unite the people of diverse regions and ethnic backgrounds, it will continue to witness a level of political instability far into the future. And this unstable politics will reflect in the country’s international conduct. A broadly acceptable constitutional settlement will thus be the first meaningful step towards developing a clear foreign policy orientation. The problem is: Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli and his UML party simply do not seem interested in such settlements made at the cost of, in their calculation, their vote banks up in the hills.

@biswasktm

You May Like This

Souls of My City: Home away from home

“Everybody here is so friendly that it feels like home,” says Sanjay Thakur. He is a 28-year-old barber from Bihar,... Read More...

A home away from home

We all know how difficult it is to find hotel rooms that won’t take a chunk of our vacation budget... Read More...

A Home Away from Home

As far back as I can remember, whenever my semester report card came out, I would always proudly show it... Read More...

Just In

- Rising food prices cause business slowdown

- Madhesh Province Assembly meeting postponed after Janamat’s obstruction

- Relatives of a patient who died at Karnali Provincial Hospital 6 days ago refuse body, demand action against doctor

- Khatiwada appointed as vice chairman of Gandaki Province Policy and Planning Commission

- China's economy grew 5.3% in first quarter, beating expectations

- Nepal-Bangladesh foreign office consultations taking place tomorrow

- Kathmandu once again ranked as world’s second most-polluted city

- PHC endorses Raya as Auditor General

Leave A Comment