OR

Private schools missed an opportunity to demonstrate that “private” and “school” could go together in socially responsible ways

Can a word change the course of history? Probably not. But words, whether thoughtful or off-hand remarks, are indicators of the forces shaping history.

In April 2018, Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’, co-chairman of Nepal Communist Party (NCP), inaugurated the fiftieth-year anniversary celebrations of a school in West Chitwan. Speaking at the event, Prachanda reportedly said that the education quality of community schools should be improved and that private schools should be controlled.

Exactly what he said remains unclear. As a gathering with little political significance, the event wasn’t reported extensively. His speech was probably impromptu, delivered off-the-cuff.

How seriously should we look for meaning in such impromptu remarks? Nine months later, Prachanda’s impromptu remarks from that afternoon rang with heavier meaning.

Earlier this month, the High-Level Education Commission, mandated to prepare a proposal on education policy for Nepal, held consultative meetings toward finalizing its report. A key recommendation in the report was that all private schools should convert to non-profit trusts or foundations within seven years.

Shortly after the commission’s recommendations were announced, BBC Nepal’s coverage of the report featured an interview that discussed whether Prachanda might have said “monitor” or “control” of private schools.

By then it didn’t matter whether Prachanda had said “monitor” or “control.” The whole idea of “private” being able to provide education through private schools had already been discredited.

Speaking to BBC Nepal, Gangalal Tuladhar, a member of the high-level education commission who is also a former education minister, a member of parliament, member of Nepal Communist Party and a key ideological architect of the commission’s report, described the recommendations as a first step toward the long-term vision of a socialist education.

Exactly what he meant by “socialist education” remains unclear, in much the same way on whether Prachanda said “monitor” or “control” remains unclear. But one thing did become clear: In public perception, the credibility of “private” schools in the delivery of education had been significantly tarnished.

Private schools under attack

In September 2017, only a few months after Prachanda’s speech in Chitwan, the High-Level Education Commission was constituted, actually reconstituted, through a decision of the Cabinet. The commission’s reconstitution was itself mired in controversy.

Initially established in 2015, the high level education commission was disbanded because of friction within the commission members. A new one was established under a fresh leadership with members that were much more closely aligned to the communist party and the current government.

The commission was mandated to review and make recommendations to the government on Nepal’s education system, all the way from primary school to higher education and in the context of the new federal structure. It was given just five months to submit a report that could shape the future of Nepal for generations.

The commission turned out to be extremely efficient. Despite the gravity of the issues under consideration, the commission wrapped up its work in record time. No other commission in the history of Nepal has completed its work in such record time, let alone one dealing with such complex weighty issues. Perhaps we should pause to consider whether Prachanda’s remarks in Chitwan were really impromptu after all. Or did it signify what was to follow?

The commission’s recommendations will go to government, where it is likely to be adopted. But even if adopted, whether the recommendations are implemented or not is irrelevant. For now, the commission’s work is done. Nepal’s communist parties have won the battle on education.

There are approximately 5,500 private schools in Nepal which educate about 30 percent of all students. It is unlikely that within the next ten years, the government will find the resources to displace private schools while providing the equivalent quality of education.

The commission is at best a temporary advisory body. Subsequent governments could just as easily change course and issue a new set of policies. Just as the old commission from 2015 was disbanded and a new one formed, this commission’s recommendations could easily be undone.

In practical terms, the proposed change in structure from private ownership to non-profit trust is mostly semantics. Trusts could be just as profitable as private for-profit enterprises. Trusts could operate with as much incentives for profit as not-for-profit trusts. Regulatory oversight, monitoring and quality control could be just as effective with for profit-enterprises as with trusts.

The recommendations of the commission in terms of squeezing the space for private schools can never practically be implemented. But then, the recommendations were never intended for implementation in the first place.

Discrediting ‘private’

The recommendations were intended to shape the narrative about private schools, to discredit the “private” of private schools. The commission’s discourse on private schools fits an all too familiar pattern of discrediting and undermining the legitimacy of other institutions outside of the state, most notably the private sector.

The commission’s report adds to the growing narrative that is seeking to expand the role of the state and erode the space for other institutions that are as equally socially responsible as the state—other non-state institutions that can legitimately provide important social services.

Those representing the interests of private schools walked neatly into the narrative trap laid out for them like a mouse walks into a cage full of cheese.

Representatives of private schools were quick to oppose the commission’s recommendation. But instead of arguing that “private” and “school” could go together in socially responsible ways, they focused on the need to protect private property.

The headline sound bite from Rajendra Baniya, General Secretary of Private and Boarding Schools of Nepal (PABSON), the largest association of private and boarding schools in Nepal, summed up the response.

“We will not agree to removing the company. Issues on protection of individual wealth and ownership are contained within a company. A person’s investment is in there. At least, the interest on the loan taken from banks to open schools must be paid back,” Baniya told BBC Nepali Service.

Other arguments were also forwarded: such as, the commission had misinterpreted the constitutional goal for free and universal education and a trust was not the appropriate structure. But the headline focus on recovery of investments simply ended up validating the core narrative the commission had laid out—for private schools it was all about investments and profits, not education.

For those of us who watched the debate from outside, the response of private schools was extremely disappointing. They missed an opportunity to demonstrate and argue that private schools, even when acting as private enterprises, can be socially responsible and are important to addressing Nepal’s educational needs.

Instead the focus on investment recovery undermined the contribution that private schools have been making in Nepal’s education.

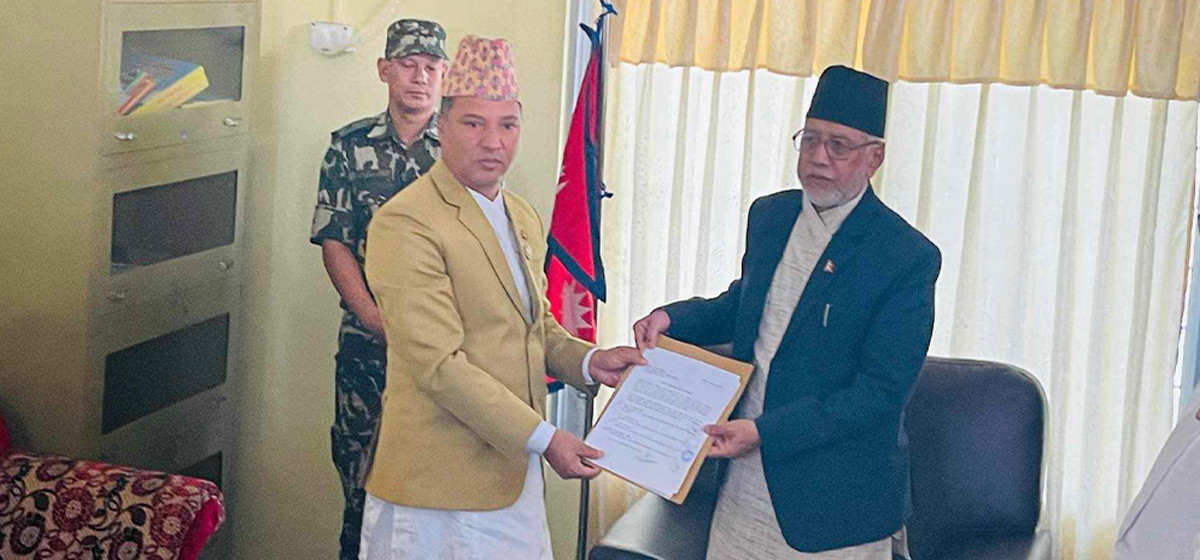

So, when the Minister for Education, Giriraj Mani Pokhrel, also the commission’s chairman said that no protests were necessary because they would not let any of the investment remain unrecovered, he seemed to have bridged the gap and ended the debate. And in generous good faith, the commission increased the adjustment time to convert private schools into a non-profit trust from seven to 10 years.

In public perception, this debate is now over. Another institution, private schools, has now fallen. The march toward a socialist order continues.

Bishal_thapa@hotmail.com

You May Like This

In defense of private schools

Why can’t an entrepreneur open a private school and make profit in the process? Why don’t we let the market... Read More...

Abolish private education?

To truly counter arguments about abolishing it, private sector education must rethink its socioeconomic roles in the new national... Read More...

Genealogy of xenophobia

In a country burdened by ethno-nationalism, self-destructive jingoism and hubristic self-importance, the politics of prosperity is merely a façade... Read More...

Just In

- 12-hour OPD service at Damauli Hospital from Thursday

- Lawmaker Dr Sharma provides Rs 2 million to children's hospital

- BFIs' lending to private sector increases by only 4.3 percent to Rs 5.087 trillion in first eight months of current FY

- NEPSE nosedives 19.56 points; daily turnover falls to Rs 2.09 billion

- Manakamana Cable Car service to remain closed on Friday

- Nepal govt’s failure to repatriate Nepalis results in their re-recruitment in Russian army

- Sudurpaschim: Unified Socialist leader Sodari stakes claim to CM post

- ED attaches Raj Kundra’s properties worth Rs 97.79 crore in Bitcoin investment fraud case

Leave A Comment