OR

Has the water and sanitation situation in the country improved in comparison to what was promised and the amount of money spent for that purpose?

We know that the government spends large sums of money through budget allocations to meet its own expense as well as to provide necessary services to public, including for drinking water and sanitation.

The government allocated a total of Rs. 14.8 billion out of total budget of Rs. 522.6 billion in 2014/15 for spending on drinking water supply and public sanitation projects. This makes the water and sanitation spending about three percent of total budget. Finance Minister Dr Ram Saran Mahat at the time declared that the amount he had allocated was intended “to provide basic level of safe and sufficient drinking water service by 2017 to all Nepalese people as per national target.”

All the subsequent budgets including for the current year’s allocation of three percent target to meet water and sanitation needs of entire population over the ‘next three years.’ The current year’s budget presented by Finance Minister Dr Yuba Raj Khatiwada in July 2018 made the same kind of commitment. “I have allocated budget to ensure [all] people’s access to clean drinking water within the next three years [by 2021],” he said.

Promises not to keep

Has the water and sanitation situation in the country improved in comparison to what was promised and the amount of money spent for that purpose? There are no data available to evaluate effectiveness of water and sanitation programs. But the impression one gets by reading through the annual budgets and looking out for results, it becomes obvious that budgets are being used as hoax, to present a grand vision of the future that is unlikely to be realized in the first place. None of the budgets presented over the past ten years I have followed gives a rundown of actual progress made over the past year, past five or ten years, even though, in most instances, almost all of the allocated money has been spent.

Looking specifically at the drinking water and sanitation sector, there is hardly any evidence that situation has improved. Most people are deprived of these services as always. Although almost all households in the country have access to drinking water source—through tube wells, wells, streams and, in some urban places, public pipes—the truth is almost all of water people use, including for drinking, is untreated and unfit for human consumption.

Piped water in urban area is loaded with harmful substances largely because water coming through pipes is contaminated from defective sewer pipes that have not been replaced or checked for leaks and corrosion and are installed at small distances from the drinking water pipes. In Madhes, underground water is the main source of drinking water supply that contains fecal coliform bacteria and arsenic. Such conditions pose health risks to people.

Hiding truth

Despite the government’s repeated claims of success in improving the quantity and quality of drinking water, evidence shows rural population has no access to piped water. Some of the urban areas have such access but supply is erratic and, in dry season, it dwindles to just couple of hours a week or none.

Water quality in Kathmandu Valley is of low grade for a number of reasons but the leakage from the city’s sewer pipes is main. The problem is that sewage being discharged into the city drains has no outlet out of the city boundary and so it gets dumped into Valley’s rivers and streams. The sewage carried by these rivers and streams are generally slow-moving because of their low water levels during the dry season that lasts eight months. Consequences for city living is horrific with the foul smells permeating the city air all hours of the day and accumulated sewage becomes host for many disease-causing insects.

Situation is much worse in towns which have no access to safe piping system for waste, water or sewer. People draw water from underground wells dug at shallow depths. In rural areas, there is no system of waste or sewer collection which means that they get spread over a larger area and aren’t as visible as in urban areas. But still the village population suffers from the consequences of drinking arsenic water. Unhygienic conditions get further worse in small towns and villages by the practice of open defecation that continues to persist in most places to this day.

Huge returns

Government’s failure in improving people’s access to safe drinking water and in management of public waste puts all of its development initiatives in doubt. Investment in water and sanitation sector is multiple times more beneficial to society than other investments. One recent United Nations report notes that in developing countries as much as 80 percent of diseases are linked to poor water and sanitation conditions. The mass-killer diseases like cholera, typhoid, hepatitis, malaria, and gastroenteritis all originate from consumption of contaminated water and absence of safe disposal of public waste which, however, continues to be a low priority for governments, including in Nepal.

The incidence of unhygienic living conditions in Nepal affects a large segment of population. Further, diseases caused by waterborne insects and viruses not only cause illnesses but, like malaria, they debilitate the affected person for life. In the background of such reading of waterborne diseases, United Nations calculates that each dollar spent on reducing the incidence of water-borne diseases adds economic value to society by as much as three to four dollars, the highest return from any other investment.

Therefore, the first order of business for the government should be to maximize investment in public water supply and sanitation services, including a safe disposal of public waste. As things stand, both are done very poorly in the Kathmandu Valley and situation in rest of the country is more appalling where virtually no control mechanisms exist to ensure safe drinking water supply and improve the disposal of public waste. The consequence is that water streams and water reservoirs all over the country have become the objects of public health hazards and no longer serve as public places that earlier enriched community living by creating open spaces.

There is compelling reason for budget allocations to reflect the benefit they bestow on the society. If the budget priorities are scaled in this way, fund allocated to water and sanitation sector would be much larger than currently. Budget spending on water and sanitation has been steady at about three percent of total spending, which is inadequate. Assessed as a share of GDP or total national income, water and sanitation spending comes to just over one percent, compared to four to five percent of GDP equivalent spent in many other countries that maintain high standard of public hygiene.

This means that public spending for water and sanitation sector needs to increase ideally to four percent of GDP and 10 percent of total budget spending.

We can assume that investment of private money in this sector is likely to be minuscule or nonexistent, which means that all of investment funding in this sector needs to come from public funding.

We are failing our people by keeping water and sanitation investment low, which is just a fraction of what is needed. It is true that committing of four percent of GDP equivalent of public money for water and sanitation services will reduce funding for other many items, perhaps significantly, but the high payoff expected from making this kind of switch holds the prospect that the country will be set on path to high income growth and improved living conditions.

The author worked as a Senior Economist at IMF in Washington DC

sshah1983@hotmail.com

You May Like This

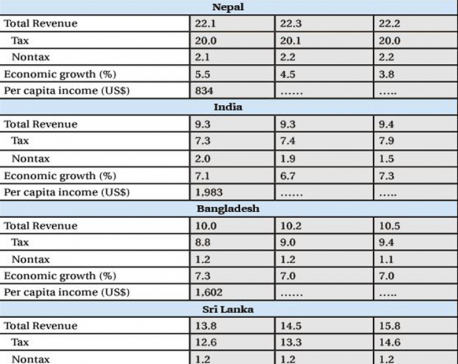

Tax exploitation in Nepal

High taxation policy pursued by Nepal has worked as a powerful drag on the economy by hurting private sector incentive... Read More...

Path of peril

Even though politics of here and now demands repositioning of Nepali Congress, playing to the religious gallery might prove to... Read More...

Tap the opportunities

Low level of economic integration combined with untenable trade deficit is making Nepal vulnerable to external shocks ... Read More...

Just In

- Govt receives 1,658 proposals for startup loans; Minimum of 50 points required for eligibility

- Unified Socialist leader Sodari appointed Sudurpaschim CM

- One Nepali dies in UAE flood

- Madhesh Province CM Yadav expands cabinet

- 12-hour OPD service at Damauli Hospital from Thursday

- Lawmaker Dr Sharma provides Rs 2 million to children's hospital

- BFIs' lending to private sector increases by only 4.3 percent to Rs 5.087 trillion in first eight months of current FY

- NEPSE nosedives 19.56 points; daily turnover falls to Rs 2.09 billion

Leave A Comment