OR

We need to study how collective action in community-managed forests impacts measures of forest quality

Last week, over 1500 researchers and policy practitioners from both developing and developed nations came together in Gothenburg, Sweden for the World Congress of Environmental and Resource Economists. The week-long academic conference entailed a vibrant discussion of cutting-edge research on the economics of global climate change, including potential policy solutions that improve both economic growth and environmental outcomes such as air and water quality. The program offered key lessons on three core dimensions of environment policy that Nepal can benefit from: management of forests, policy design to improve agro-environmental characteristics and adaptation to natural disasters.

First and foremost, forest management should be at the forefront of policy discussions. Amid high rates of deforestation and forest fires, Nepal has carried out community forestry initiatives to provide local users with control over natural resources. This is important because forest use in Nepal is directly linked with food and energy needs of rural inhabitants. There is well-documented evidence of improved economic well-being among community forest user groups in Nepal.

Recent research highlights that households relying on community-managed forests for firewood spend significantly more on food consumption than those dependent on government-managed forests. While the positive effect of community forestry on food consumption is more pronounced among non-high caste households, empirical findings show that household participation in community forestry can be an effective means of addressing food insecurity in a developing country.

However, there is no rigorous empirical evidence on the role of community-managed forests in improving environmental outcomes. Nepal faces the recurring threat of forest fires every year, with reported damage of over 12,000 community-managed forests in 2016. Despite the importance of forest fires as a public policy issue, it is unclear whether rural households understand the risk that environmental disasters pose to their homes, and carry out any measures to mitigate such risks.

Assessing the impact

We need to study how collective action in Nepal’s community-managed forests impacts different ecological measures of forest quality. This is important as collective action potentially offers large positive effects on carbon stocks. Moving forward, environmental and resource economists in Nepal need to consider public perception of risk towards forest fires and shed evidence that contributes to designing policies aimed at mitigating environmental disasters.

Second, policies that improve both agricultural and environmental outcomes in rural Nepal are equally important. A comprehensive investigation of the impact of a fertilizer subsidy program in the hilly region during the first three years of the policy implementation shows that subsidy, on average, leads to a 38.7 percent increase in fertilizer use among recipients. Empirical evidence, however, suggests that fertilizer supply shortages and varying access to the subsidy lead to lower agricultural yield among smallholder farmers. Given that input subsidy programs can widen economic disparities between smallholder and large farmers, it is necessary to evaluate how agricultural policies are implemented in different parts of Nepal.

It is also worth highlighting that fertilizer run-off results in nitrogen pollution, causing $200-800bn worth of annual damage across the world. Unfortunately, policy makers in Nepal have failed to consider environmental repercussions of fertilizer subsidy programs. From a policy perspective, resource economists and agronomy experts in Nepal need to estimate the change in fertilizer use required to minimize nutrient pollution and enhance water quality. Going forward, it is critical that we augment empirical research on agro-environmental economics with detailed farm visits and assess the effects of agricultural fertilizer use on nutrient pollution across water sites in Nepal.

Coping with disasters

Finally, there is a need to study how individuals cope up with natural disasters and adapt in response to negative environmental shocks. A forthcoming research article shows that infants born in districts severely affected by the 1988 earthquake are 13.8 percent less likely to complete middle school and 10 percent less likely to complete high school. More important, empirical estimates demonstrate that only children belonging to upper caste groups recovered from the 1988 earthquake in the long run. This suggests that earthquakes widen the gap in human capital between low caste and upper caste groups.

To ensure a sustainable recovery in the aftermath of the 2015 earthquake, policy makers need to incorporate general lessons learned from 1988 earthquake. Empirical research shows that the 1988 earthquake exacerbated differences in educational attainment across caste groups. Thus the government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) should efficiently allocate adequate funds for humanitarian support, targeting low caste individuals who suffered significant losses from the earthquakes.

The World Congress in Sweden showed that economists are able to provide rigorous empirical evidence on different aspects of agro-environmental sector. Yet, it is unfortunate that academics and policy makers, both inside and outside of Nepal, appear to work independently. The World Congress is a positive step towards filling the void between researchers and policy practitioners. Unless policy makers in Nepal encourage academics and relevant stakeholders to disseminate their findings in a more collaborative setting, enriching knowledge acquired from careful research and field visits will go in vain.

The author is a PhD candidate of environmental and resource economics at University of Massachusetts Amherst

jpaudel@umass.edu

You May Like This

Dramatic action needed on climate change: UN

PARIS, MAy 1: The world must redouble efforts to halt global warming before it is too late, the UN's climate... Read More...

Climate change taking its toll on Karnali

JUMLA, Oct 17: It would take no more than two hours to fetch water for Gauri Sunar when she was a... Read More...

G7 leaders divided on climate change, closer on trade issues

TAORMINA, May 28: Under pressure from Group of Seven allies, U.S. President Donald Trump backed a pledge to fight protectionism... Read More...

Just In

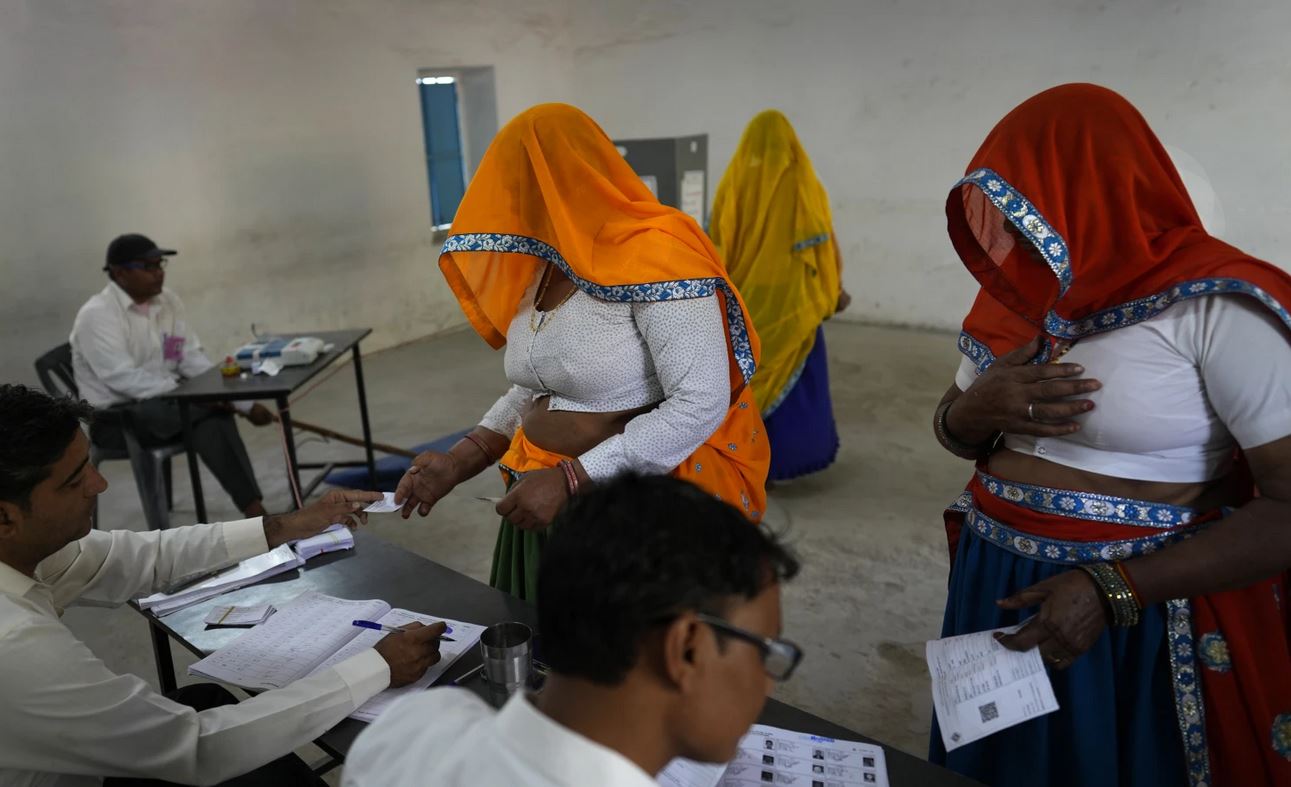

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

- 352 climbers obtain permits to ascend Mount Everest this season

- 16 candidates shortlisted for CEO position at Nepal Tourism Board

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment