OR

Easing the lockdown and its impact on women

Published On: June 6, 2020 01:38 PM NPT By: Swasti Gautam

For women in Nepal, easing of the lockdown has potential to further compound pre-existing gender inequalities based on caste, class, geographical location and various religious conventions and beliefs.

As the world, including Nepal, progresses towards easing the lockdown, it is imperative for Nepal to find its way through this new world order post the COVID-19 pandemic. However, due to the rising COVID-19 cases, there are various challenges in the forefront that need to be dealt with economic and political foresightedness. Especially for women in Nepal, easing of the lockdown has potential to further compound pre-existing gender inequalities based on caste, class, geographical location and various religious conventions and beliefs. There is a possibility that the current situation could be worsened by an inevitable economic crisis given the distinct lack of consideration by the state to accept women as equal citizens rather than a ‘category’ that needs to be considered while ticking a few boxes. A particular focus on women and their needs is crucial to ensure that we traverse to the second stage of this pandemic smoothly.

Crisis of social care

The crisis of social care, although widely prevalent, gets little to no attention in our national debates. Nepal over generations has been governed by various micro-level forces which have played a role in relegating women to the private sphere. It is an established fact that once the lockdown is eased, the COVID-19 cases will inevitably increase and so will women’s responsibilities as caregivers in intra-household relations especially during times of illness and disease of a family member. As Nepal is one of the poorest nations in South Asia and the life expectancy of women is lower than that of men, this exposure to illness, combined with minimal decision-making powers within the household puts women in an extremely vulnerable position, even more so in these uncertain times.

It is not unknown that most women working in the informal sector, primarily as domestic workers or as care workers, have already lost their jobs. The loss of jobs for such care workers would lead to an increased burden on the women who employ them for unpaid care. As a result, the majority of women will be disproportionately impacted during and after the lockdown, be it those who provide these services or those who need them. Adding on, the dilemma of returning or not returning back to work may affect vulnerable and pregnant women unreasonably who may either be forced to work or may be at the risk of losing their jobs. These factors are likely to cause an increased economic crisis and time poverty among women.

A huge proportion of working women (66.5 percent) in this country are in the informal sector (many of them are low wage earners or part-time workers) and are likely to lose their jobs as an immediate aftermath of the pandemic. This lift in the lockdown and the looming economic crisis could affect women particularly in sectors such as healthcare, tourism, hospitality, retail and child care who will struggle to revive from this crisis. Sadly, women from the marginalized sections of the society are more likely to do the precarious jobs placing them in the frontline to absorb much of the shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Who is a citizen?

Nepal government’s response to various crises in the past, including the 2015 earthquake, has shown how systematic failures put women in the most vulnerable category owing to their high exposure to risk, limited access to information, greater social and psychological pressure and low life expectancy rates. The definition of a citizen that needs to be ‘protected’ during these uncertain times often seems limited. Women’s needs, their situation or their socio-economic state in general and particularly in times of crisis often fail to become a part of the national discourse. These issues often get ghettoized in certain regional and political spaces or within one ministry that is expected to handle all issues related to women.

This lack of consideration or ‘othering’ of women’s needs was clearly visible even this time as the essential relief items did not include something as basic as sanitary products needed for menstrual hygiene. Although distressing, it is not surprising given that the general access to menstrual health itself is limited. Women’s needs were not even taken into consideration while building ad-hoc quarantine facilities in most districts. The beneficiaries of these items were expected to be ‘daily wage earners’ which the state assumed to be young working men. Adding on, thousands of men, women and children stranded at the Indian borders, in the scorching heat without food or water shows how the priorities of the state is not protecting its citizens but only protecting citizens that belong to a certain (mostly privileged) category.

Mental and physical safety

Post-earthquake we have also seen how high levels of tension within the family could lead to an increase in domestic violence. Likewise, the lockdown due to COVID 19 and increasing lack of basic resources within households has further exacerbated internal tensions. Easing of the lockdown could have prolonged mental and physical pressures on these victims, survivors and those trying to recover from these traumatic experiences, especially considering the Nepalese context where less severe forms of sexual and physical violence by the male partners is considered common and even acceptable. This will have grave psychological repercussions especially considering, resources such as distress help lines, hotline services and rescue shelters for domestic violence survivors are limited in the country.

Furthermore, the existing health care system tends to exclude the most vulnerable groups in the society based on their caste, class, ethnicity and economic status, and within each category, women suffer the worst of the discrimination. As the lockdown eases the ill-equipped healthcare system coupled with diversion of maximum resources towards tackling the pandemic could lead to a lack of adequate health care services (overcrowded hospitals/clinics with poor hygiene and sanitation) depriving many of basic antenatal and postnatal healthcare. It could limit the access to contraceptives and basic sanitation facilities for many in need, including young adolescent girls. Unless a considerable amount of funds and resources are allocated for these services, the state would be unable to provide women with even the basic facilities.

Way forward

Despite accounting for 54.54 percent of the national population, women still remain a minority in our country. Hence, for us to make a transition into the post-corona era efficiently, it is important now more than ever to not only enhance funding for frontline care services but also invest in infrastructure for reproductive health and child care services. The time demands investment in social infrastructure, including healthcare and education. We not only need a strong government but also a robust social security system to ensure that the massive barriers for women between providing basic services and accessing those services are removed.

It is important to consider every woman of this country (who are involved in both paid and unpaid labor) as an important socio-economic force that not only upholds the economy but is also integral to the socio-cultural stability of the country. And lastly, it is not only the responsibility of the government but we need the help of each individual, each household, each classroom and every public space to bring out the holistic change that we are looking for.

The author holds a Masters Degree in Gender, Media and Culture from London School of Economics and Political Science

swasti30@gmail.com

You May Like This

Existential crisis

With an electoral rout of small Madhesi parties in Province 2, the struggle for separate Madhes province or Madhesi-only province... Read More...

ICC Advisory Committee formed to solve cricket crisis

KATHMANDU, Sept 4 : With a view to solve the problems plaguing Nepali cricket, the International Cricket Council (ICC) has declared... Read More...

Just In

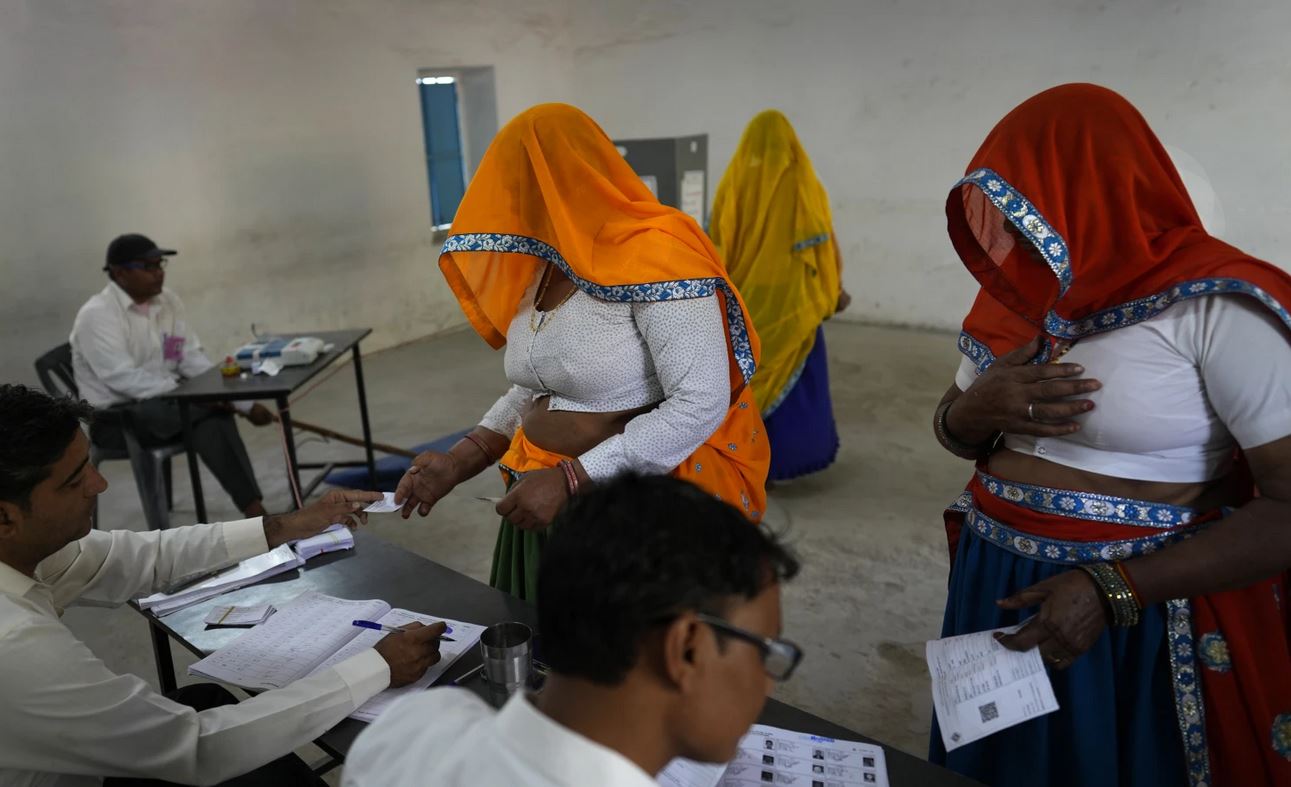

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

- 352 climbers obtain permits to ascend Mount Everest this season

- 16 candidates shortlisted for CEO position at Nepal Tourism Board

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment