OR

Madheshi politics

One alternative would involve re-incarnating late King Mahendra’s crisp labeling of his regime’s opponents as anti-national elements

This is history now but not a distant history. The topic of this write-up is the last CA election held in November 2013, just over three years ago. It is not clear yet whether the next election—this time a full-fledged parliamentary election—will be held in 2018 or 2019.

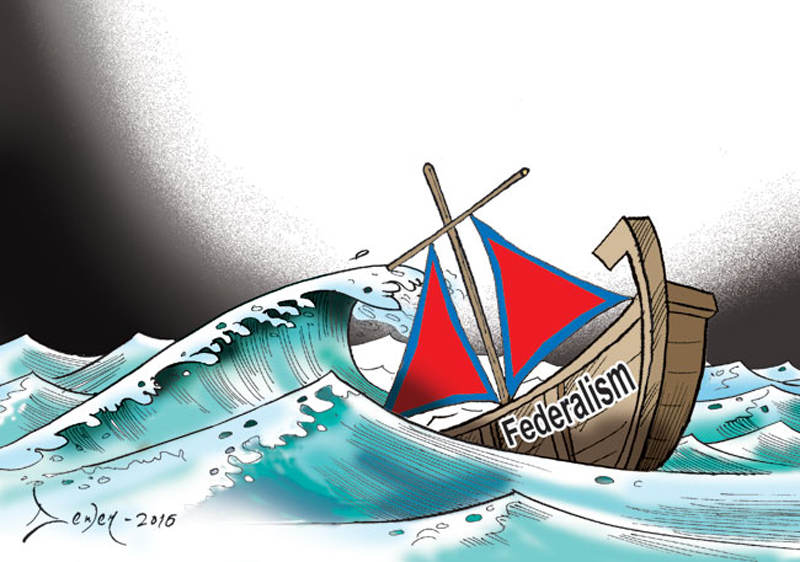

The most significant event of post-election years—2013 through to 2017—was not the earthquakes that struck central Nepal in April 2015, killing close to 10,000 people, or even the constitution that was promulgated in June 2015 but still is debated. In my view, the disruptions caused by the escalation of disturbances in Madhesh region, including, most importantly, the closure of Nepal-India border from late 2015 to early months of 2016, should rank as number one event in that period.

In terms of politics, Madhesh Uprising made little gain but caused tremendous hardship to the people, especially in Kathmandu where essential items for daily living were either unavailable or could be bought only in black market for as much as 10 times the market price.

Life in Madhesh and in rest of the country seemed to be returning to normal but it has once again been roiled by police firing on protesters in Saptari, in which five people were killed and dozens wounded. In Madhesh, such events quickly lose their political meaning and assume an ethnic edge as most protestors were Madheshis while most security personnel came from Pahade communities.

It is not yet clear how the Madheshi leadership would respond to this event but they have already withdrawn their support for the Prachanda government, and they will probably launch a national movement to create instability and disorder. However, before this non-cooperation strategy started, cracks have appeared in Madheshi Morcha, again showing the illusiveness of Madheshi unity, a factor that has plagued Madhesh Movement since its birth after the start of multiparty politics in 1990.

What is next, no one knows. My view is there is nothing Morcha or Madheshi leaders can achieve through agitation, except playing the role of albatross in the body-politic of Nepal. They are likely to disturb Nepali politics, but not disrupt it altogether. However, such a state of affairs will do no good to the Madheshi cause and won’t be helpful in promoting national welfare. A further point to emphasize is that the whole country, including Madheshi people, are being hoodwinked by Madheshi leaders who claim to represent Madhesh—they do not.

To demonstrate this, recall the outcome of the last CA election in 2013, in which a total of 124 parties took part, including 19 labeled Madheshi parties. It is amazing how badly they performed. Altogether, Madheshi parties won just 12 seats of the 240 seats under the first-past-the-post component, or just 5 percent of total seats, whereas Madheshis comprise 50 percent of national population. Looking at popular votes, Madheshi parties secured just over 1 million, less than a quarter—23.4 percent—of all votes cast in Madhesh. On a national level, Madheshi parties tallied just 11 percent of 9.04 million total votes.

For Madheshi parties, these numbers aren’t just surprising but startling. There is hardly a comparable case in the world whereby those championing the cause of a particular ethnicity got such a less small share of votes from these very ethnicities. For example, in recent elections in Ethiopia, Sudan, Israel and Scotland, almost the entire contingent of ethnic voters opposing the national government voted for the main ethnic party. This increased the legitimacy of that party and, in a few cases, improved the bargaining power for those advocating independence.

We can then conclude that Madheshi people are being deceived by their own leaders. Instead their agitation has been harmful in that it has pushed Madheshis out of mainstream politics into a sort of a pariah status. This is largely an outcome of the greed and falsehoods that characterize Madheshi leaders.

Pahade leaders are fully aware of the predicament of common Madheshis. But they can do little to change politics in Madhesh, as they can’t seem to escape the exploitative Madheshi parties to fight for their own destiny. The other option is for Madheshi people to align themselves with mainstream parties. This will clip the wings of Madheshi leaders and improve their accommodation into mainstream of national politics.

An alternate approach to bringing Madhesh into Nepali mainstream is to follow Bhutan’s example on a much smaller scale but which is loaded with meaning: improving the status of Madheshis and helping Madhesh utilize its full potential to contribute to the making of a prosperous Nepal.

This alternate policy would involve re-incarnating late King Mahendra’s crisp labeling of his regime’s opponents as anti-national elements—people who at the time were fighting against the Panchayat rule and for the restoration of democracy. Pahade government of today can use such labeling to identity Madheshi groups agitating for autonomy and independence. The number of people falling into this net, including the Madheshi leaders, may not be more than 25,000.

The fact is that these agitators—most notably the so-called Madheshi leaders—don’t realize that Madhesh and Madheshis aren’t the same entities they were fifty, forty, or even thirty years ago.

Pahade natives now hold sway—not in numbers but in terms of their grip over local economies and cultural practice—in all but a dozen of the country’s 75 districts, compared to 22 districts Madheshi leaders claim to be Madhesh territory.

Narrowing down the concept of Madhesh to a more functional category, only eight districts comprising the current No. 2 province can be said to be real Madhesh, which also happens to be the center of Madhesh Movement. In fact, in most of the country, most people have either not heard of Madhesh Movement or are indifferent to its message.

Madheshi parties didn’t get even half of the votes in these Madhesh-centered eight districts and still a lower percentage of CA seats compared to the mainstream Pahade parties won there. So it is hard to justify bringing the whole of Madhesh under the protest umbrella of Madheshi leaders.

The national leaders now have a choice—to let the whole of Madhesh suffer indefinitely because of the agitation led by a narrowly-based Madhesh Movement or to clear out the agitators to make room for more positive and unifying forces in Madhesh. This can be labeled the political version of what economists call constructive destruction—you have to root out the old evils to make room for the positive forces to grow a new economy—which can be used, in this case, to create a new Madhesh.

The author teaches economics at Northern Virginia Community College in the US

sshah1983@hotmail.com

You May Like This

SAARC member states agree to contain COVID-19

KATHMANDU, March 26: The health officials of the eight SAARC member nations held a video conference in a bid to contain the novel... Read More...

Environment Minister Pandit pledges elaborative measures to control air pollution

KATHMANDU, Feb 27: Minister for Population and Environment, Lalbabu Pandit, has said companies producing non-biodegradable plastic products would be banned. Read More...

Security measures completed for local-level poll

KATHMANDU, May 13: The security management in view of the local-level poll being held tomorrow has been completed. As many... Read More...

Just In

- Altitude sickness deaths increasing in Mustang

- Weather forecast bulletin to cover predictions for a week

- Border checkpoints in Sudurpaschim Province to remain closed till Friday evening

- Gandaki Province Assembly session summoned

- CM Karki to Speaker: Resolution motion for vote of confidence unconstitutional

- EC reminds all for compliance with Election CoC

- 13 killed, several injured after strike at Al-Maghazi refugee camp in Gaza

- NA team leaves for Solukhumbu to launch Clean Mountain Campaign

Leave A Comment