OR

Sandesh Paudyal & Binaya Bogati

Paudyal is construction entrepreneur and student of political economy and Bogati has B.Com (Hons) from Hindu College, New Delhinews@myrepublica.com

More from Author

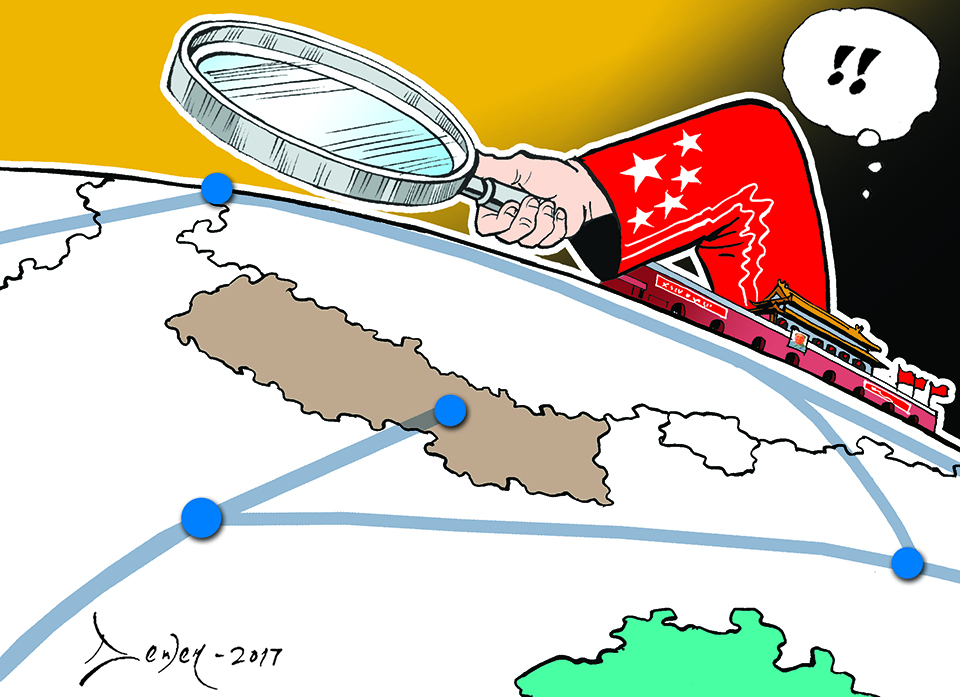

The potential benefits are juxtaposed with concerns stemming from contrasting political winds of the dragon and the tiger.

By any count, this is by far the biggest infrastructure drive the 21st Century has seen. The Belt and Road Initiative, magnum opus and pet project of President Xi Jinping, has consequences that traverse well beyond the infrastructural node of development and if successful, will put China at the center of the world, eventually giving rise to a new political and economic order.

The revival of historic Silk Road and maritime silk route has till date been upvoted by more than 70 countries. The initiative, which includes investment in roads, rails, ports, pipelines and communications will connect Central Asia, Southeast Asia and Europe in ways unprecedented. The initiative touches the life of 65 percent of world population and represents one-third of global economic output.

It is not hard to guess that the BRI has gotten mixed response. “I expect no country to create obstacle in this great development initiative,” said Venezuelan Prime Minister Nicolas Maduro. This is important because South America isn’t part of this initiative. Nonetheless, around 32 head of states attended the BRI forum, which goes to show how well it was received. But not in India.

Moving away from its usual conciliatory statements, India was sharp in its criticism. It said China in its foreign dealings must follow good governance, rule of law, openness, transparency and equality—these are not the traits you generally associate with how China conducts its development. It also criticizes the initiative on environmental and geopolitical grounds. But it is important to highlight that India is itself a member of both AIIB and BRICS, the banks which will finance major parts of the initiative.

Big dollars

The US has recognized the BRI, albeit after leaving the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) on shaky grounds. Critics believe this leaves US flat-footed and plays into China’s hands. The Europeans are generally skeptic, but with (16+1) strategy involving countries in and outside EU, BRI can safely be assumed to have a European impact. China cleverly leveraged its financial stronghold in Europe, while many countries were barely managing to stay afloat after the financial crisis of 2008. It acquired strategic ports, which would later form an important part of its overall maritime strategy. Further, China has partnered with countries in strategic maritime routes, such as Sri Lanka, Indonesia and Oman to bolster the BRI.

China is investing approximately US $1.4 trillion in the initiative. Most of the financing will come from Chinese government banks, multilateral banks like AIIB and BRICS, as well as government debts. It is not hard to guess that China wants to use its vast foreign reserves, which it currently holds as low-return American bonds and securities. Making RMB a global currency for one may be the most important financial objective of China. But there are gray areas too. Chinese banks are raising billions of dollars to fund the initiative. The big question is: if any of the projects were to fail or become non-performing assets, how much collateral damage will the global economy suffer?

Such questions are hard to answer but the bottom-line is that Chinese banks are giving loans to foreign governments to make these projects a reality. But these governments will have to eventually pay China back. What will happen then? This is the major fear vis-à-vis BRI in the financial market.

“Countries along the Belt and Road have their own resource advantages and their economies are complementary. Therefore, there is a great potential and space for cooperation,” goes the Chinese official version. Such assurances have failed to alleviate the fear of financial pundits.

Ethiopian lesson

For example, China undertook a rail project to connect Addis Ababa with Djibouti. Of the total amount, Chinese financial institutions funded 70 percent and the rest was given by the beneficiary government. If the Ethiopian government makes optimum use of connectivity to create new space for trade and commerce and develops requisite human resource for technology transfer, then the project will be win-win for everyone involved. If not, the Ethiopian government would have to sit on a huge pile of debt.

It would be an understatement to say Nepal needs to move fast in infrastructure development. The current ones are appalling and hardly put Nepal’s economy on the desired growth trajectory. A recent World Bank report clearly mentions that Nepal needs to invest around 2.5-3.5 percent of its GDP on infrastructure if it is to become a proper developing country by 2030. Financing is tough, which may nonetheless be managed, but other soft things like construction experience, technology and human resource are also missing.

Just as in Ethiopia, Chinese financing in Nepal may prove problematic, and there is a larger geopolitical challenge too. India, the predominant power in Nepal, has given the BRI a dampened response. With India and US reviving trans-pacific co-operation, Nepal could find itself tangled in a geopolitical quagmire. This is evident from Nepal taking its time to sign the BRI MoU and sending a deputy prime minister, and not a prime minister, to the BRI summit. India would want to perpetuate its dominant influence in Nepal, for security and energy concerns. It will be interesting to see if the political leadership in Nepal can play both cards right. For the benefit of all, it definitely should.

In theory, there is an immense opportunity. The BRI will allow Nepal to look beyond India and China for trade and commerce, to develop requisite infrastructure to attract more tourists, to learn from construction experience of China, and to improve the capabilities of its human resources, among other things. Rails, roads and communication will go a long way to realize the dream of a prosperous Nepal.

Tough balancing act

But there is a flip side too. If not handled properly Nepal could find itself caught in a geopolitical game between India and China which it cannot control. Volatile Nepali governments won’t help either, as seen with recent Budhi Gandaki project cancellation. Also, the concerns related to finance are real. Nepal can be saddled with a big debt burden if China really invests heavily in its infrastructure. This is why the financing models need to be thoroughly studied. There can be damage to ecology and environment, too, even with China’s reiteration of its adherence to environmental standards. The bottom-line is that a half-baked plan on BRI will create more chaos and vulnerability. Political parties take note.

We remain fairly optimistic that the BRI will do more good than harm to all parties involved. There is a risk of polarization at the global level, which in turn has the potential to upset global harmony that has been there for the past 40 years. It is China’s initiative with obvious financial and political ambitions but it would also be a stretch to equate it with Chinese imperialism. For once the benefit of doubt shall go to China. For all the countries involved it is advisable to assess their own situation before diving in and to cut their coat according to their cloth.

The potential benefits are juxtaposed with concerns stemming from the contrasting political winds of the dragon and the tiger. But a lot will depend on how political leaders negotiate with China without intimidating India. This is a gargantuan diplomatic endeavor that Nepal cannot get wrong.

Paudyal is construction entrepreneur and student of political economy and Bogati has B.Com (Hons) from Hindu College, New Delhi

You May Like This

Why is Nepal Dallying BRI Projects?

Nepal could benefit from better connectivity ties with its northern neighbors through BRI projects but to be able to do... Read More...

Prez Bhandari for Trans-Himalayan Connectivity under BRI

BEIJING, April 28: President Bidya Bhandari has said that the Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI) of China will support the... Read More...

China to expand trade, investment in South and Central Asia under BRI

BEIJING, Oct 19: In what may be taken as a move to further deepen its trade relations with South and Central... Read More...

Just In

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

- 352 climbers obtain permits to ascend Mount Everest this season

- 16 candidates shortlisted for CEO position at Nepal Tourism Board

- WB to take financial management lead for proposed Upper Arun Project

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment