OR

Shortage of medicines

There is a troubling mismatch between government commitment and delivery when it comes to supplying each and every Nepali with essential medicines. On paper, over 100 essential medicines are available to the general public, at zero cost for the most needy.

But the harsh reality is that many places are today running short of these essential drugs, in many cases even if people are willing to pay for them. For instance, over the past five months, 14 districts have been without paracetamol, five districts without iron pills and four districts without life-saving antibiotics. This should not be happening. Every year, the government purchases medicines worth around Rs 800 million and distributes them among the 75 districts. As any government procurement process is by its nature cumbersome and time-consuming, there is a provision which allows each district to buy medicines worth up to Rs 300,000 without bidding; this is to ensure that no district runs out of essential medicines at any time. That, at least, is the theory. What is actually happening is that regional medical stores and district hospitals are regularly without medicines as they don’t have any money to buy them. The Rs 300,000 promised to each district seldom comes through on time.

Meanwhile, the old bureaucratic blame game is in full swing again. The Ministry of Health blames the Department of Health Services—which is tasked with purchasing essential medicines and supplying them to districts—for the medicine shortage. Department officials, for their part, ask what they can do when the ministry doesn’t supply them with funds on time, or about the fact that the procurement process can take up to nine months. Also, the department officials wonder why even the districts that have received timely funds are running short of essential medicines. But the district health bodies have complaints of their own: they have not received any funds and, moreover, their repeated requests for timely disbursal are conveniently ignored by the center. In the absence of medicines at government-run facilities, people have no option but to rely on the more expensive private medical stores (at least in places that have private stores). This still leaves out the millions of poor folks who are completely reliant on the around 4,000 public health institutions in the country for their health and wellbeing. Many of them will needlessly suffer (and die) for the want of most basic medicines like paracetamol and ORS.

We learn that the health minister, Gagan Thapa, is working on a new online platform to track the movement of essential medicines in Nepal so that bottlenecks can be quickly identified and removed. Such a system to make the medicine procurement process transparent is overdue. But that won’t be enough. Not all medical facilities have easy access to internet. Even when it is available it might take many years to fine-tune the online tracking system and train medical personnel to use it properly. What Thapa can do immediately is trim down the lengthy procurement process. Nine months is far too long for procurement of essential, often life-saving medicines. If international standards are any guide, there is no reason it cannot be cut short by at least a month or two—a significant amount of time during which many lives could be saved.

You May Like This

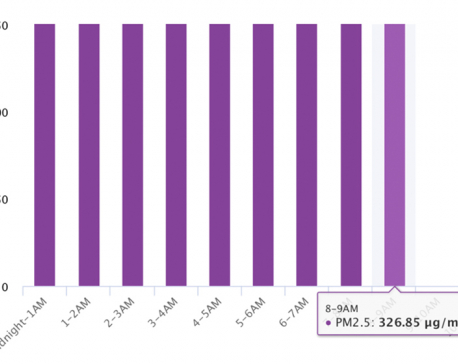

Air pollution deadly in the morning and evening hours

The Department of Environment is planning to recommend the government to implement odd-even rule for vehicles, and close schools and... Read More...

Betrayed by delay

Many houses would have been rebuilt by now if the government had not promised reconstruction grants ... Read More...

Few days delay in printing ballots 'not serious'

KATHMANDU, March 18: The Election Commission (EC) has delayed its plan to print the ballot papers starting from Saturday, citing lack... Read More...

Just In

- Nepalgunj ICP handed over to Nepal, to come into operation from May 8

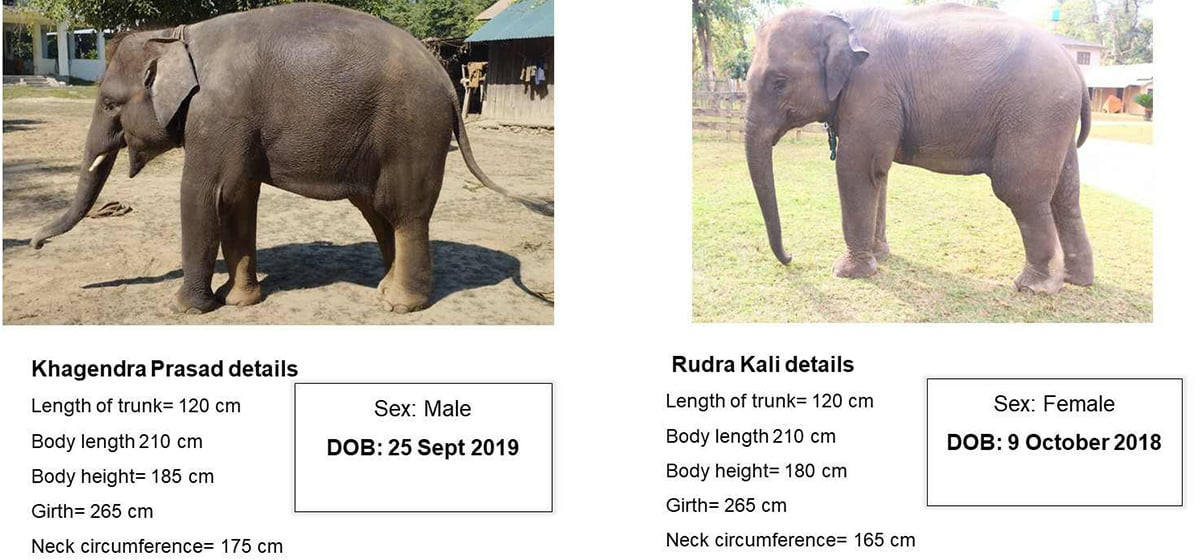

- Nepal to gift two elephants to Qatar during Emir's state visit

- NUP Chair Shrestha: Resham Chaudhary, convicted in Tikapur murder case, ineligible for party membership

- Dr Ram Kantha Makaju Shrestha: A visionary leader transforming healthcare in Nepal

- Let us present practical projects, not 'wish list': PM Dahal

- President Paudel requests Emir of Qatar to help secure release of Bipin Joshi held hostage by Hamas

- Emir of Qatar and President Paudel hold discussions at Sheetal Niwas

- Devi Khadka: The champion of sexual violence victims

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment