OR

Rune Bennike

The author is based at the University of Copenhagen. He has been doing social scientific research in Nepal for over a decade and is currently conducting postdoctoral research on post-disaster tourism and land management in Manaslu Conservation Areanews@myrepublica.com

More from Author

Nepal’s tourism has seen its share of tragedies over the past years. Further tragedies will undermine development potential of new trekking destinations such as Manaslu

BOOM goes the first one. Shortly afterward, the sound of a second blast roars even louder through this section of Budhi Gandaki river valley. The tourists and guides around us appear confused. Disparate discussion ensues. How many blasts were there going to be? Will it be clear to go now? Some begin to move out from the riverside boulders where we have taken shelter, others linger on the sun-baked rocks waiting for a signal. Then, a whistle cuts through the murmur of voices. A man in army fatigues yells down and waves for us to come back up to the trail. We are, I guess, some 30-40 people—guides, porters and tourists—gathered to wait for the blast. Now, we are all herded quickly past the little bhatti where we were initially stopped and on towards the blast zone.

With additional blows of the whistle, an army-man is directing us to cross the debris zone, dust still hanging in the air. We are uncertain about what to do. I have my one-year old son in a baby-carrier on my back. Having trekked and climbed a fair bit in the mountains, I can easily tell that the man-made landslide created by the blast is far from stable. The rocky outcrop above appears loose, and the gravelly slope, which we are to cross, is steep and exposed. While we desperately discuss the possibility of going back the way we came, crossing the river, and taking an alternative trail, the army personnel seems to be getting impatient. In English, we are told that it is safe to cross and that we need to get going. In Nepali, however, my friend is told that it may be a good idea to drape his backpack over his head as protection from falling rocks. At the same time, an excavator begins to move on the road above our heads, knocking down rocks around us. We yell for him to stop, but feel the pressure. We need to go, and in the end, we do. In the course of a few, frantic minutes we cross the loose slope trying to balance the sureness of our footing with the urgency to cross the hazard zone as quickly as possible.

Eventually, we arrive safely on the other side of the blast zone. Nevertheless, I curse myself for not heeding my friend’s advice, for not taking the longer and less-travelled trail on the other side of the river. Surely, this was a stupid thing to do. Our individual lack of responsibility this day in April, however, mirrors a larger, institutional irresponsibility. Why is the army blasting their way to new road development in the middle of tourist season in what is regarded as Nepal’s foremost ‘up-and-coming’ trekking destination?

Desire to rise

Over the past decades, Nepal has increasingly been tying its ambition to graduate from a ‘Least Developed Country’ to a ‘Developing Country’ onto the development of the nation’s tourism industry. Much in line with international recommendations, the Nepali government regards tourism as a major potential source of foreign exchange earnings. Tourism—and trekking tourism in particular—is seen as a sector well suited to distribute those earnings widely across the country, providing people living in the most remote corners of the nation with a unique opportunity to generate income. Major development initiatives, such as the Great Himalaya Trail Development Project, have actively and successfully promoted new trekking areas to international tourist. Often described as the ‘next Annapurna’, Manaslu is prime among these new areas. Over the past decade visitor numbers have climbed steeply.

Despite an expected downturn caused by the 2015 earthquakes, visitor numbers were quick to recuperate. In 2016, 4780 foreign tourists visited the Manaslu Conservation Area. A total of 645 of these came in April—the most popular month for springtime trekking. However, this year, local residents and springtime visitors had to cross the man-made hazard zones left behind by the ongoing road construction. If no-one has been hurt or killed this spring, we need to be thankful. If no-one is to be hurt or killed over the monsoon or in the peak autumn trekking season, we need to be thoughtful.

The fault lines

Following the 2015 earthquakes, a Swiss-Nepali team undertook a thorough geological survey of the Budhi Gandaki river valley. The conclusion was clear. The riverside, where the main trail is located, present a natural fault-line in the landscape prone to landslides. Subsequently, a World Food Programme project upgraded alternative trails on the other (eastern) side of the river, to allow for the transport of basic necessities into the area on mule-back.

This alternative trail, however, added substantial difficulty to the first days of the Manaslu trek. In response, a coordinated effort by the Manaslu Conservation Area Project and SAMARTH - Nepal Market Development Programme, ensured the development of a variation on the main trail, balancing relative safety with accessibility. This included the establishment of Nepal’s first cantilever bridge. The trail still crosses a few major landslide zones, but these are signposted and appear reasonable stable. Now, despite these recent initiatives, road construction is introducing new, more acute hazards to the area. Today, the alternative trail provides a better option for the safety conscious but few tourists take it and few trekking companies seem to promote it. In the meantime, the main trail—now partway road—continues to be the lifeline to the area as well as the bread and butter of the budding tourism industry.

Where is the inter-governmental coordination here? While Nepal Tourism Board is actively promoting Manaslu to foreign visitors, the Army is blasting away in the middle of tourist season. Don’t get me wrong here. I am fully aware of the national priority given to north-south road development as well as local interest in road connectivity. It is fascinating to watch how the Army manages to pave the way into such remote and difficult locations. A major feat, indeed. Obviously, the stakes are high, be the economic or political, real or imagined. But there are conflicting interests that need to be reconciled and coordinated here. No Trekkers Information Management System (TIMS) cards or any of the other registration measures adopted by Nepal in recent times will save you from rocks falling from an unstable slope above or from slipping on the narrow path through the debris of a blast zone.

Nepal’s tourism has seen its share of tragedies over the past years. Further tragedies will undermine the development potential of new, up-and-coming trekking destinations such as Manaslu and leave locals, who are investing heavily in the prospects of future tourism, in arrears. As tourism promotion and north-south road construction continues, in parallel, it is vital to everyone—locals and foreigners alike—that the government takes a lead in coordinating the efforts.

The author is based at the University of Copenhagen. He has been doing social scientific research in Nepal for over a decade and is currently conducting postdoctoral research on post-disaster tourism and land management in Manaslu Conservation Area

runebennike@gmail.com

You May Like This

Development Committee asks govt to increase development expenditures to 90 percent

KATHMANDU, Dec 8: Today's meeting of the Development Committee (DC) under the Legislature-Parliament has directed the government to increase the... Read More...

President Bhandari underscores common viewpoint on development agenda

BIRATNAGAR, Dec 24: President Bidya Devi Bhandari has urged all political parties to move ahead on development agendas by forging... Read More...

Development Committee redirects authorities to reform information sector

KATHMANDU, Sept 14: Legislature-Parliament's Development Committee today redirected the authorities concerned for effective implementation of the past instructions on reforming... Read More...

Just In

- One arrested from Jhapa in possession of 43.15 grams of brown sugar

- EC to tighten security arrangements for by-elections

- Gold price drops by Rs 2,700 per tola

- Seven houses destroyed in fire, property worth Rs 5.4 million gutted

- Police pistol missing after drug operation in Bara, investigation underway

- Truck carrying chemical used in drugs catches fire

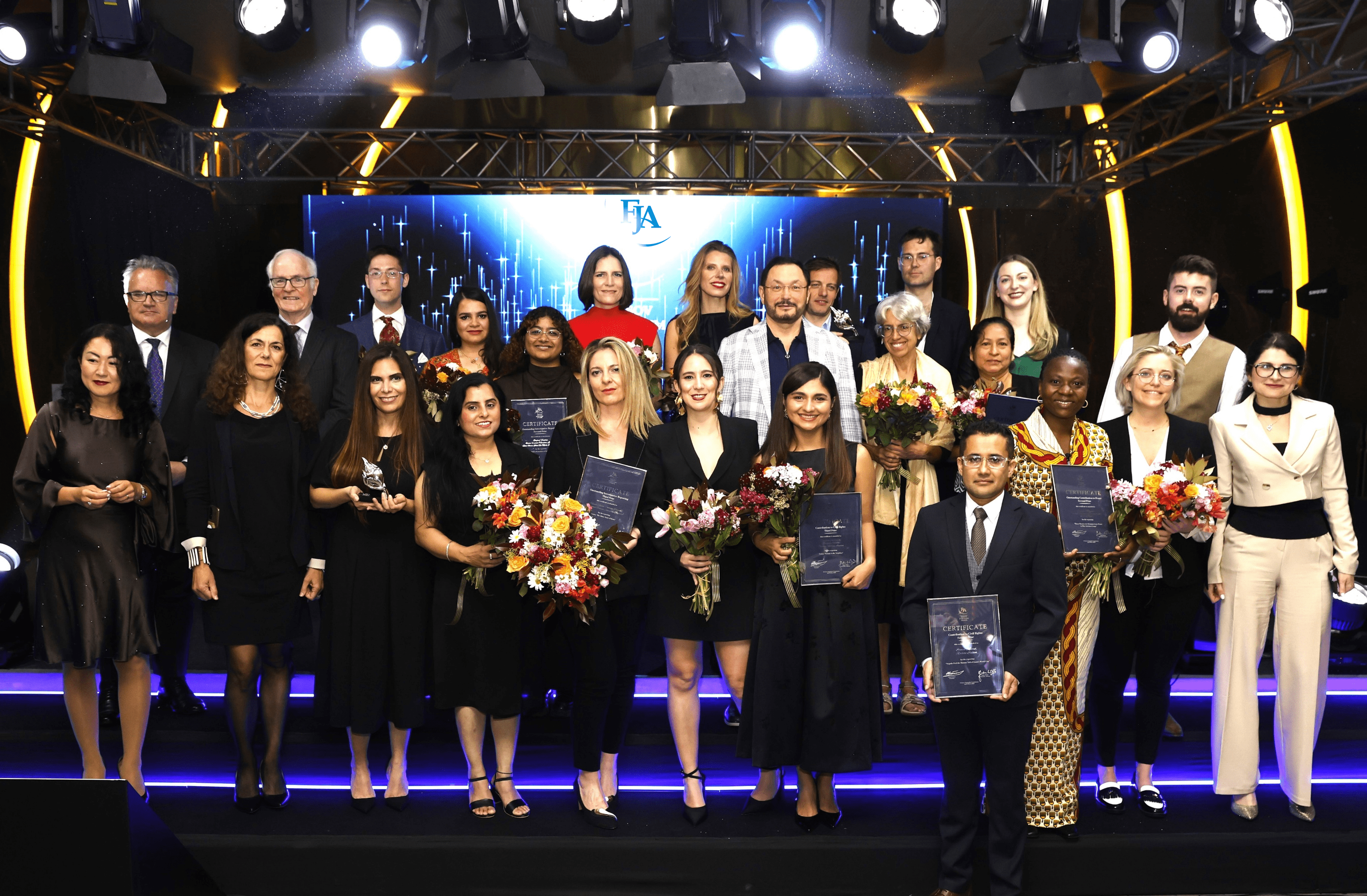

- Nepali journalists Sedhai and Kharel awarded second prize at Fetisov Journalism Awards for their exposé on worker exploitation in Qatar World Cup

- Devotees gather at Balaju Park for traditional ritual shower at Baisdhara (Photo Feature)

Leave A Comment