OR

Ethiopian Airline crash

Basic B737 has been flying since the early 60s and was commercially successful as it had no other aircraft type to compete against

The aviation world was rocked by Ethiopian Airline’s (ET) recent crash involving a B737Max8 that happened less than five months after Lion Air (JT) crash in Indonesia. Normally, the period is not crucial, but the common narratives seem to show very identical circumstances with both crashing within few minutes after takeoff. That seems to be so, as it has now been irrevocably confirmed by the black box’s data of flights JT610 and ET302. Further, Ethiopian had sent black boxes (CVR/FDR) to the French Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (BEA) in defiance of pressure from US side to have it shipped to National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) instead. The question being, how and why this aircraft type was found safe to fly by Boeing and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

Tracing the past

But to get to the core of B737Max issue we need to look at Boeing’s past. The basic B737 has been flying since the early 60s and was commercially successful especially as it had no other aircraft type to compete against in the short range capability. As for the long or inter-continental sector, the B707 had almost total monopoly for the same reason. In the mean time, 3 engine B727 was developed to suit both the shorter and medium range sectors with increased carrying capacity. As B727 became older, Boeing developed B757 as its replacement. As like any later model of aircraft, B757 came with better engine, longer reach and increased capacity. But it was never foreseen that B757 would also be able to fly some transatlantic routes done by B707 earlier. Surprisingly, it did so with better economics and was quite popular especially among airlines as it was neither too big nor too small. But it was a cruel irony that this “unrecognized trait” was discovered by airlines only after its production was stopped. Further, to make it worse, Boeing had already scrapped all its tooling by then. If not, it may surely have been resuscitated as airlines still lament at not being able to get a true B757 replacement. It can be safely assumed that RA might have opted for new B757s instead of A320 if that was the case. The big void left by termination of B757 came as a god send opportunity to Airbus.

Like B737, Airbus had also developed A320 to cater to the shorter single aisle market. It went on further to create an extended version like A321. As such, Airbus sees all derivatives like A321/A319/A318 etc fall under the basic A320 family for having “cockpit commonality”. This was the single factor that helped make them become a commercial success. As the competition between the two giants in the narrow body sector was at its peak, Airbus was seen to be more active in developing the A320 family of aircrafts by constantly tweaking the product to deliver better economics. In fact, Airbus was the first to introduce fly-by-wire (FBW) concept and tiny winglets to its A320s. Winglets have since become much more prominent. But new engines that consume less fuel makes them even more attractive. Fixtures like winglets etc that help reduce drag are important no doubt but improved engine helps airline fare better with costs of ATF on a rising trend.

To fill the B757 void Airbus brought out A321neo (new engine option) with a bigger, more efficient engine and increased range. It was immediately hailed as the next best thing. It is still not as good, but most airlines that loved B757 found it acceptable enough to order it in large numbers. Boeing was literally in panic mode seeing the market it dominated once being taken over by Airbus. Max is seen as the version Boeing brought out by to challenge A321neo’s onslaught. But it should be remembered that the A320 family that began in 1980s was a more modern in most respects than B737 stuck in the 60s. But the B737Max was the result of a rushed job on the part of Boeing to get it to the market at the earliest. That is precisely why it ended in two most horrendous accidents resulting in 346 deaths.

Fitting bigger engine required Max to undergo number of changes than other B737 versions in use. As the engine had much bigger diameter it had to be placed in a much higher and more forward position on the wings. Such an unusual placement caused the plane’s nose to pitch up affecting plane’s lift characteristics in some conditions. But Boeing, most probably for marketing reasons, saw it wiser to install corrective software called “Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System” (MACS) without letting either airlines or pilots know about it. The motive was to push Max as like any other B737 as regards to its flying characteristics and required no additional training for pilots. MCAS was designed to automatically push nose down when it was pointed up beyond a safe angle that risked high speed stall.

But it did not happen as designed, more so as pilots were unaware of MACS and that situation had triggered it due to unreliable airspeed data in Lion Air’s case. This accident was projected as typical case of low cost airline, that too an Asian, flown by unqualified pilots. Boeing even tried to brush aside this eventuality by saying that pilots had known about MCAS. But it was even more baffling, with regard to Ethiopian case, as pilots were “aware” about MCAS issue and were trained to tide over the problem. Both Boeing and FAA were truly in a fix to explain.

Exposing the lie

But Dominic Gates, an aerospace reporter in Seattle Times rips apart Boeing lie in an elaborate recent article titled “Flawed analysis, failed oversight”. He says it was against a long held Boeing tradition of giving the pilot complete control of the aircraft, MCAS was designed to act in the background, without pilot input. Adding further, he says, FAA, citing lack of funding and resources, has over the years delegated increasing authority to Boeing to take on more of the work of certifying the safety of its own airplanes. Doing so, in my opinion, was unpardonable.

It also reveals how the FAA managers prodded subordinates to speed the process as the MAX was lagging nine months behind the rival Airbus A320neo. There are other more revealing technical details that are beyond the scope of this short piece. All in all, Boeing will have to explain why those fixes were not part of the original system design. And the FAA will have to defend its certification of the system as safe, he concludes.

It is usually incumbent upon the related ministry or aviation authorities of a country to ground an aircraft on grounds of being unsafe. Apart from ET/JT it was tiny Singapore which not just grounded Max but also barred it using its airspace, making it the first. It gradually snowballed with more countries following suit. It was only the USA which resisted doing this till the last. With Canada falling in line, USA was left with no other choice. At the end, it was gloomy looking Donald Trump making a grand gesture by “temporarily grounding” all types of Max on the grounds of safety. People wondered why it was not NTSB or FAA doing it instead. One aviation forum comment reasoned “he had to intervene because Boeing and FAA had become paralyzed.”

harjyal@yahoo.com

You May Like This

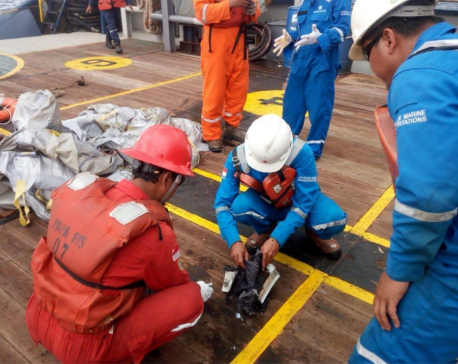

Indonesian plane with 189 aboard crashes into sea near Jakarta, wreckage found

JAKARTA, Oct 29: An aircraft with 189 people on board is believed to have sunk after crashing into the sea off... Read More...

Canadian aviation expert joins Nepal plane crash probe team

A Canadian aviation expert has joined the probe body in Nepal to investigate into the plane crash of US-Bangla Airlines. Read More...

No apparent survivors in Texas balloon crash

LOCKHART, July 31: A hot air balloon carrying at least 16 people caught on fire and crashed in Central Texas on Saturday, and... Read More...

Just In

- Govt receives 1,658 proposals for startup loans; Minimum of 50 points required for eligibility

- Unified Socialist leader Sodari appointed Sudurpaschim CM

- One Nepali dies in UAE flood

- Madhesh Province CM Yadav expands cabinet

- 12-hour OPD service at Damauli Hospital from Thursday

- Lawmaker Dr Sharma provides Rs 2 million to children's hospital

- BFIs' lending to private sector increases by only 4.3 percent to Rs 5.087 trillion in first eight months of current FY

- NEPSE nosedives 19.56 points; daily turnover falls to Rs 2.09 billion

Leave A Comment