OR

More from Author

Blockade created favorable climate for unscrupulous traders to do more transactions off the official radar

The recent unofficial Indian blockade had a debilitating effect on Nepali economy already crippled by poor growth in manufacturing and agriculture, high inflation, never-ending blackouts and low infrastructure investment. Illegal trading activities grew not only in border towns, but also in urban areas where demand for essential goods is relatively high.

Consequently, there has been an upsurge in Underground Economy (UE). Unbridled rise in inflation, increased cost of production and poor supplies of necessary goods made matters worse. UE includes not only illegal activities, but all legal ones that are untraceable and hence not taxable and thus also not reflected in national accounts.

Normally, the size of UE is much bigger in developing countries as compared to developed countries. Research shows that size of shadow economy is between 35 to 44 percent of GDP in developing countries whereas it was between 21 to 30 percent for transition countries and between 14 to 16 percent for OECD countries during the early 1990s.

The UE adversely affects government revenue, primarily due to tax evasion arising from unrecorded trade and business transactions. The revenue growth of Nepal in past two decades also exhibits a trend that substantiates the prevalence of a large UE. For example, the average growth of all major taxes except excise duties actually declined after 2000/01. There was a surge in revenue growth following the introduction of voluntary disclosure of income in 2008/09. But revenue growth has been stagnant since and has even started to decrease in recent months.

The new estimates for 162 countries published in the World Bank Policy Research Working Paper show that the weighted average size of shadow economy was around 37 percent of official GDP of Nepal, which places the country in 64th position out of 162 countries in the world and in second position in South Asia after Sri Lanka. Surprisingly, the study shows the Indian economy's share was only 22 percent during the same period.

However, Arun Kumar, author of Black Money in India, argues that the black economy in India is worth a whopping US$500 billion—almost half the size of official economy. Therefore, it would not be illogical to argue that the magnitude of Nepal's shadow economy, which shares 1,850-km open border with India, must have also increased to similar levels.

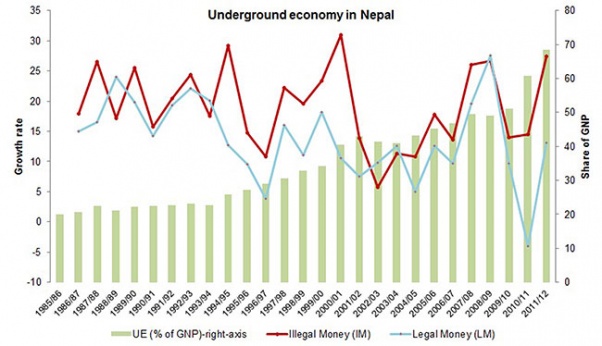

I led a research under University Grants Commission which was later published in the Economic Journal of Development Issues on growth of shadow economy in Nepal. Currency Demand Method was applied using time series data from 1985 to 2012. The study shows that the growth rate of illegal money (IM) has mostly been higher than the growth of Legal Money (LM). This proves that UE is on the rise in Nepal despite the multiple reform measures introduced during the period.

The average growth rate of UE was 19 percent between 1991 and 2000. It stabilized at 17 percent between 2001 and 2010 but increased to 32 percent in 2011 and 2012.

The stability between 2001 and 2010 may be partly attributed to the anti-corruption campaign in Nepal that has become stronger since 2000. This may be due to the proactive CIAA and increasing awareness of the issue as well as pressure from Nepali civil society and donor community.

The Royal Commission for Corruption Control (RCCC) played a key role as it took action against several high-profile politicians and bureaucrats. Furthermore, the end of the decade-long Maoist rebellion might also have slowed the pace of illegal transactions (which were earlier mobilized to pay for military recruits and purchase ammunitions for the rebels).

There may be several reasons for the upsurge in last two years of study period. First, various studies on black economy of India puts it at 50 to 70 percent of GDP. Nepal, too, could have a similar UE. Second, stagnant growth of tax revenues—importantly income taxes and custom duties—in past few years further prove there have been large tax evasions; stagnant revenue growth has not kept pace with increasing imports. Finally, rampant corruption, the prevalence of cash economy, open border and poor regulation of trade and financial sector might have added to such alarming growth of black economy in Nepal.

The recent blockade created favorable climate for unscrupulous traders to do more transactions off the books. The effect of this is going to linger for years even if the market supplies normalize in the days ahead.

Often politicians and even high level officers are involved in UE. Without taking action against them, there is an incentive for others to join the herd and earn illegally and quickly, at the cost of national treasury. The proposed AML Act has provision to increase the scrutiny of financial positions of politically exposed persons (PEPs), which is in line with the Financial Action Task Force's (FATF) revised recommendation in 2012.

Apart from this, provisions such as efficient and effective labor market regulation, cutting extra burden on formal sector and punishment and reward system in public service could help cut down UE's size.

Further, better social security and protection for taxpayers will discourage them from illegal economic transactions. Better provision of public goods and services will also help discourage people from such underground transactions. The economic blockade dealt a severe blow to the national economy. But it has also provided us an opportunity to clamp down on underground economy.

The author is an Assistant Professor at Tribhuvan University and currently a PhD Candidate at National Graduate Institute for Policy studies (GRIPS) in Tokyo

@NirmalKumarRaut

You May Like This

Why Federalism has Become Risky for Nepalese Democracy

The question arises, do federal or unitary systems promote better social, political and economic outcomes? Within three broad policy areas—political... Read More...

Nepal's Forests in Flames: Echoes of Urgency and Hopeful Solutions

With the onset of the dry season, Nepal's forests undergo a transition from carbon sinks to carbon sources, emitting significant... Read More...

'Victim blaming'- Nepali society's response to sexual violence

Multiple studies show that in most sexual assaults, the attacker is someone known and trusted by the victim. ... Read More...

Just In

- 19 hydropower projects to be showcased at investment summit

- Global oil and gold prices surge as Israel retaliates against Iran

- Sajha Yatayat cancels CEO appointment process for lack of candidates

- Govt padlocks Nepal Scouts’ property illegally occupied by NC lawmaker Deepak Khadka

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

- Court extends detention of Dipesh Pun after his failure to submit bail amount

- G Motors unveils Skywell Premium Luxury EV SUV with 620 km range

Leave A Comment