OR

Media Sutra

The coverage of Dr Govinda KC’s satyagraha is an example of the democratization of news in our mainstream media

Within a span of few years, we have seen him grow from a brief to a banner, from a profile picture to a cover photo, from a ticker to a highlight. It is seldom that our media chase a professional subject with such gusto. He competes with political figures and cultural celebrities—the mainstay of our journalistic coverage—and outshines them over and over again.

Sudheer Sharma, editor of Kantipur, says, “In recent times, he is the one”. Dr Govinda KC is the big story. Our media’s priority is generally on political news, he adds, but he is a “real hero” for he represents public interest.

It is thanks to his public cause that Dr KC is an example of a democratization of news in our mainstream media. He has singlehandedly decimated the prevailing hierarchy of news. The irony is democracy itself remains elusive and under threat from various quarters, including our elected officials.

As the nation waded into the torrents of news and watched these past couple of weeks the public health icon lying on bed in his eighth fast-unto-death campaign for medical education reform, political leaders were enacting yet another musical chair, unseating the government, and simply refusing to hear the satyagrahi. The frail doctor lying on bed was radiating love for the public. The parliament was a scene of aversion. And the news played up these episodes.

But the thing about the news is that some were complaining on social media that excessive coverage on the doctor was turning off readers. Some political cadres were calling it a “media stunt”.

My interest in this article is not so much in how journalists covered the big story, but in how the “big story” looks at himself: a rare opportunity to prod an epic story subject, the journalistic process viewed from the other side. Opinion reported.

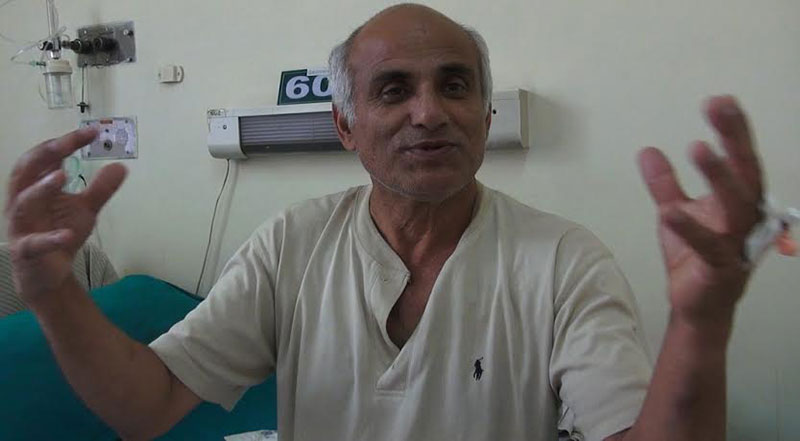

Being a story is not an easy task, at least for starters. In his cabin at Teaching Hospital where he was recuperating, I asked Dr KC this past Friday how it feels to be in the media spotlight. Throughout the conversation he refers to himself as “us”, suggesting that he owes his friends for the teamwork.

In the beginning, he said, he used to feel a bit uncomfortable and even shy before the media. But the need for public support to make the movement successful made their appearance in the media necessary. Moreover, he adds, their interest in the coverage is not self-serving since the fight is on behalf of the people. He gives credit to the media for public awareness on health education, and now on corruption.

As a consumer of media, the orthopedic surgeon and professor finds little time to read or watch news. It is only occasionally that he browses online news sites or watches global television channels. During the hunger strike, to conserve energy, his associates and friends read out print media to share the developing stories. Time is limited since he is always busy with teaching and with patients.

For the press, a big developing story promises scoops (remember the news video of Dr KC crying?), hence the pressure on story subject to let access to competing journalists. During campaigns his close associates coordinate media outreach. Sometimes he has to decline interview requests because of time constraints. Besides, he is often in operation theatres, all dressed up and without a phone nearby. “Everyone wants to interview.

How much I can give them is another matter,” he smiles.

Globally, peaceful campaigns or movements rarely garner media coverage, because they lack the drama and conflict that is so visual in violent protests. And when they are covered, they are often framed negatively. Dr KC’s campaign is an exception. Is that because, as one journalist put it, “we don’t have that much corporate interference here in covering public interest issues”?

However, this time round some outlets, even those that supported him before, did not cover him or cover him positively, “perhaps because of pressures” from the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA). Some outlets tended to distort and omit portions of his interviews, and others aborted publication of stories about him. He believes that CIAA has been ruling by spreading fear and even neutral outlets may self-censor or cover negatively under pressure.

But he feels the media have in general internalized what he and his friends have been fighting for: affordable cost of medical education, quality medical care for all, and end of mafia rule in this sector. Dr KC believes the media understand the issues better now and do follow up on the story of the campaign that continues since a long time. He gives their performance 9 out of 10.

Sharma says the media’s role lies in drawing government’s attention to issues of public interest and they have helped to amplify the story and prod the two sides to an agreement.

Big stories, because they involve clash of interests, are prone to politicization, hence the cry of media stunt. That’s a typical foul cry by those who don’t like the news for whatever reason, says Sharma. Dr KC maintains their fight is against the establishment, irrespective of who is in power. If he had fought against the interference of CIAA chief in other sectors such as banking, that might have been political. He maintains that the CIAA chief has mounted naked intervention in the public health sector for his relatives and cronies to fulfill their vested interests. Lacking a democratic culture, our leadership has institutionalized corruption, impunity, crime, unaccountability, un-constitutionalism, and mafia rule. Instead of working for the benefit of the people, leaders are working in the interest of political parties and mafia. For the media, covering these issues is in the interest of the public and of keeping an eye on power.

Big stories often come with a moral dimension. The satyagrahi cannot tell how the idea of anasan started but any social ill gives him the drive to fight against it. Having travelled to all the districts and abroad in course of his work, often as a volunteer, he believes he understands the problems and needs of our society, for instance, privatization and centralization of medical colleges favors the 5 percent rich and does not serve the rest of the population that is poor; we need affordable public institutions. With more public medical colleges, he finds other South Asian countries better off.

Big stories have a way of igniting fire or setting precedence. With Mahabir Pun, another public icon, declaring that he might as well take the path of satyagraha to improve rural broadband services, other public sectors may soon be inspired to rise up for reforms.

The problem is we face so many challenges. And the challenge for our media, sluggish in follow ups, is to keep an eye on the overcrowded news agenda. Luckily, the medical education reform campaign has been a continuing, serial news story, Sharma says, and it has been steadily followed up. Efforts to abort the latest agreement are already underway, Dr KC alerts: “Media should be vigilant, any such efforts should be exposed right away. They should also nudge us from time to time.”

Stories like this also test journalistic professionalism. Would you participate in the rallies with a banner or simply observe and report? Sharma would not approve of journalistic activism but thinks it has not been a major issue in this story. As for Dr KC, he believes public interest is at stake in this campaign hence journalists can go to the rally as citizens but as a journalist, they should, of course, be fair in their works.

Many of these issues reflect in the coverage of other stories in the media. But once in a while, all it takes is a big story to underscore the basics.

dharmaadhikari@gmail.com

You May Like This

Not so big fish in a big pond

Krishna Prasad Sigdel’s book reads like a primer on Nepal’s foreign policy and international affairs. It also deals with the... Read More...

Idiocy of Big Three

The Big Three could have gone to Madhesh with Maithili, Bhojpuri, Tharu and Awadhi translations of constitution for Madheshi views on... Read More...

Big party leaders threaten to protest division of province 5

BUTWAL, Nov 24: Miffed by the ruling parties' plan to split some districts away from province no. 5, senior leaders of... Read More...

Just In

- Take necessary measures to ensure education for all children

- Nepalgunj ICP handed over to Nepal, to come into operation from May 8

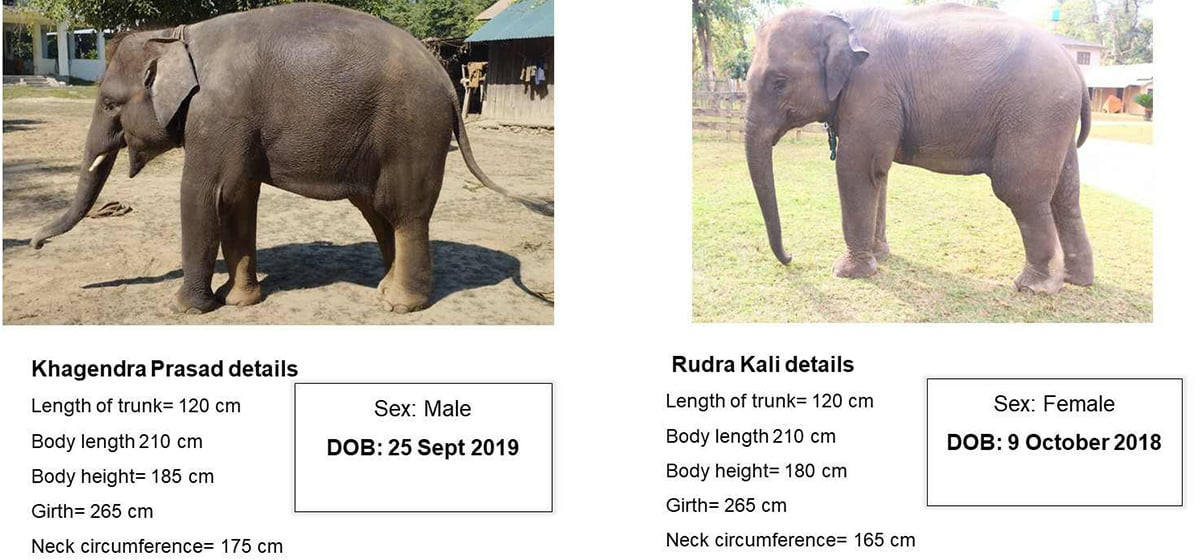

- Nepal to gift two elephants to Qatar during Emir's state visit

- NUP Chair Shrestha: Resham Chaudhary, convicted in Tikapur murder case, ineligible for party membership

- Dr Ram Kantha Makaju Shrestha: A visionary leader transforming healthcare in Nepal

- Let us present practical projects, not 'wish list': PM Dahal

- President Paudel requests Emir of Qatar to help secure release of Bipin Joshi held hostage by Hamas

- Emir of Qatar and President Paudel hold discussions at Sheetal Niwas

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment