OR

More from Author

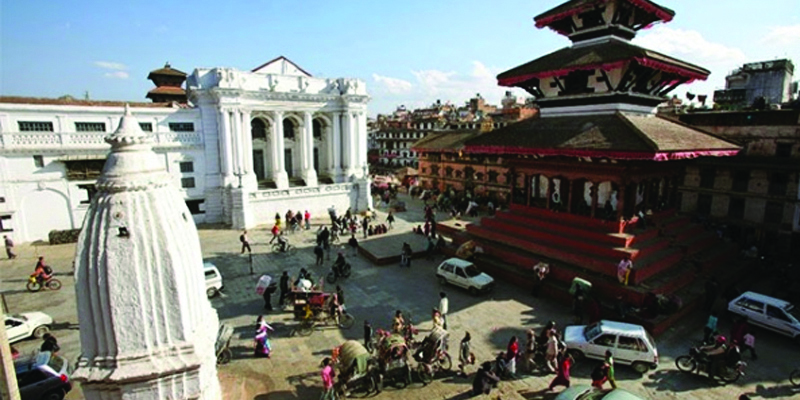

Threats to cultural heritage of Kathmandu Valley can be overcome only with an optimum level of international cooperation, greater public awareness and government’s efforts

A couple of recent reports about Kathmandu Valley drew my attention. First, there was the news related to UNESCO’s proposal to list Kathmandu Valley as “World Heritage in Danger.” And it was later followed by the report of Nepal’s plan to lobby World Heritage Committee (WHC) to retain the Valley in “World Heritage Site” list.

Nepal, at the moment, is participating in WHC’s 43rd session being held in Baku, Azerbaijan, from June 30 to July 10. Though WHC has decided not to list the Valley in ‘Danger List’ this year, this is not something to celebrate for Nepal. Our unwillingness to put the Valley under danger list is understandable but Nepal should be doing much more than just “lobbying” with WHC and take concrete actions for heritage preservation.

Kathmandu was put under Danger List in 2003 as well. The main reason then was urban encroachment.

Back then, ancient town planning traditions were being replaced by Westernized concrete buildings. But then the government implemented Integrated Management Plan as a corrective measure to address the need for long-term coordination and capacity-building for urban planning. Building laws were amended with provisions for better management of inscribed site, buffer zones and surrounding areas. Thus, with continuous collaborative efforts between the Government of Nepal and WHC, along with its advisory bodies, Kathmandu Valley regained its status of World Heritage Site in 2007.

The 1972 UN Convention concerning Protection of Natural and Cultural Heritage had put forth the World Heritage in Danger listing mechanism to ensure that the sites listed are better protected. Countries take this as a matter of shame, disgrace and adverse publicity leading them to bring in better policies and programs for heritage conservation. Being in danger zone can lead to the loss of tourism revenue as well. Thus the countries tend to work for heritage conservation when their heritages are put under danger list. In a way, danger list also works as a positive mechanism, a blessing in disguise.

Heritage of neglect

Nepal has been lobbying since 2016 to maintain the world heritage status of Kathmandu Valley. But Nepal does not seem to have worked in the same spirit to maintain, preserve and protect its heritage sites. Truth is Kathmandu Valley today is facing a graver problem of heritage conservation than in the past. In addition to rapid urbanization, rebuilding and renovation are affecting the integrity of the Valley. After the massive earthquake of 2015, all seven monumental zones were severely damaged, and nearly 33 monuments totally collapsed and 107 suffered partial damage. Demolishing gorgeous, old half-timbered buildings and replacing them with concrete buildings had already become a trend. With the damages inflicted by the earthquake on traditional establishments, the process gained further momentum.

Hence, one of the major threats to the valley, apart from those relating to rebuilding of monuments, is the disappearance of traditional vernacular settings of universal values for which Kathmandu Valley was listed as a World Heritage Site in the first place. Realizing this, WHC, in its 40th session in 2016, urged the Nepali government to take required steps “with a view to considering, in the absence of significant progress, the possible inscription of the property on the List of the World Heritage in Danger.”

Upon this request, the government of Nepal submitted an updated report in 2017 with a brief of the activities and plans being undertaken. However, International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) Report of 2017 contradicted Nepal’s claims. It illustrated many inadequacies on Nepal’s side. It pointed out that the work had barely begun on many monuments, and where it had been initiated, it was not being carried out in a systematic way with proper research. Likewise, during the 41st and 42nd sessions, the Committee emphasized that the “threat to the heritage is so considerable that the recovery should be made more effective and the scale and scope of the disaster and the response required goes well beyond the capacity and resources of the Department of Archaeology (DoA), and also considers that much greater input, collaboration and coordination of support is needed from the international community.”

The commitments Nepal makes every year in the WHC sessions have not been achieved yet. The situation of heritage conservation of the Valley is not satisfactory. In fact, the Nepali government recently proposed a bill related to regulating Guthis, social trusts of indigenous ethnic communities for heritage preservation, which gained massive opposition from the public. Guthi Bill had to be withdrawn ultimately.

Unfortunately, the government seems to view heritage and development as contradictory to each other, and it faces issues in implementing the regulations that are meant to protect Kathmandu Valley’s heritage. For example, Nepal’s Protected Monument Zone Bylaws and the Ancient Monument Preservation Act state that buildings that lie inside Hanuman Dhoka Protected Zone should be less than 35 feet in height. But as we evaluate the buildings around and inside Kathmandu Durbar Square, we see that most do not follow these standards.

Onus on government

Thus Nepal needs to strictly implement the laws related to heritage conservation. More than that, the government should realize its responsibility toward preservation of Nepali heritage. We cannot just keep urging WHC not to put in danger list without materializing our commitments into action. The Valley needs international cooperation if it wants technical assistance and expert advice which can be attained through the WHC and its advisory bodies. Nepal should be willing to use any assistance it receives as the Committee has explicitly maintained that rebuilding is beyond the capacity of Department of Archeology (DoA) alone.

What we did to delist Kathmandu Valley from danger list in 2003 offers lessons for us. Back then we corrected ourselves and were able to regain the status of world heritage after improving our plans and policies.

Perhaps, including the Valley in the danger list will make us understand the urgency of saving and preserving our heritage. Heritage is the manifestation of our beliefs, values, and ideologies illustrated through our language, practices and tangible objects. The loss of heritage, in many ways, is the loss of our identity. Threats to cultural heritage of Kathmandu Valley can be overcome only with an optimum level of international cooperation, greater public awareness and government’s efforts. It seems awareness will be raised for this when the valley is included in World Heritage in Danger List.

The author is environment and heritage rights activist

sophielisha@gmailcom

You May Like This

Campaign for Buddhist tourism

Buddha’s legacy has been monopolized by India. Nepal needs to reclaim the Buddha and his legacy as a fundamental part of... Read More...

Let the government govern

Opposition to the Guthi Bill challenged the legitimacy of the government but could it be a watershed moment that breaks... Read More...

Primitive society

Nepal’s primitiveness is starker in its villages, where public amenities such as drinking water supply, public sanitation, paved streets and... Read More...

Just In

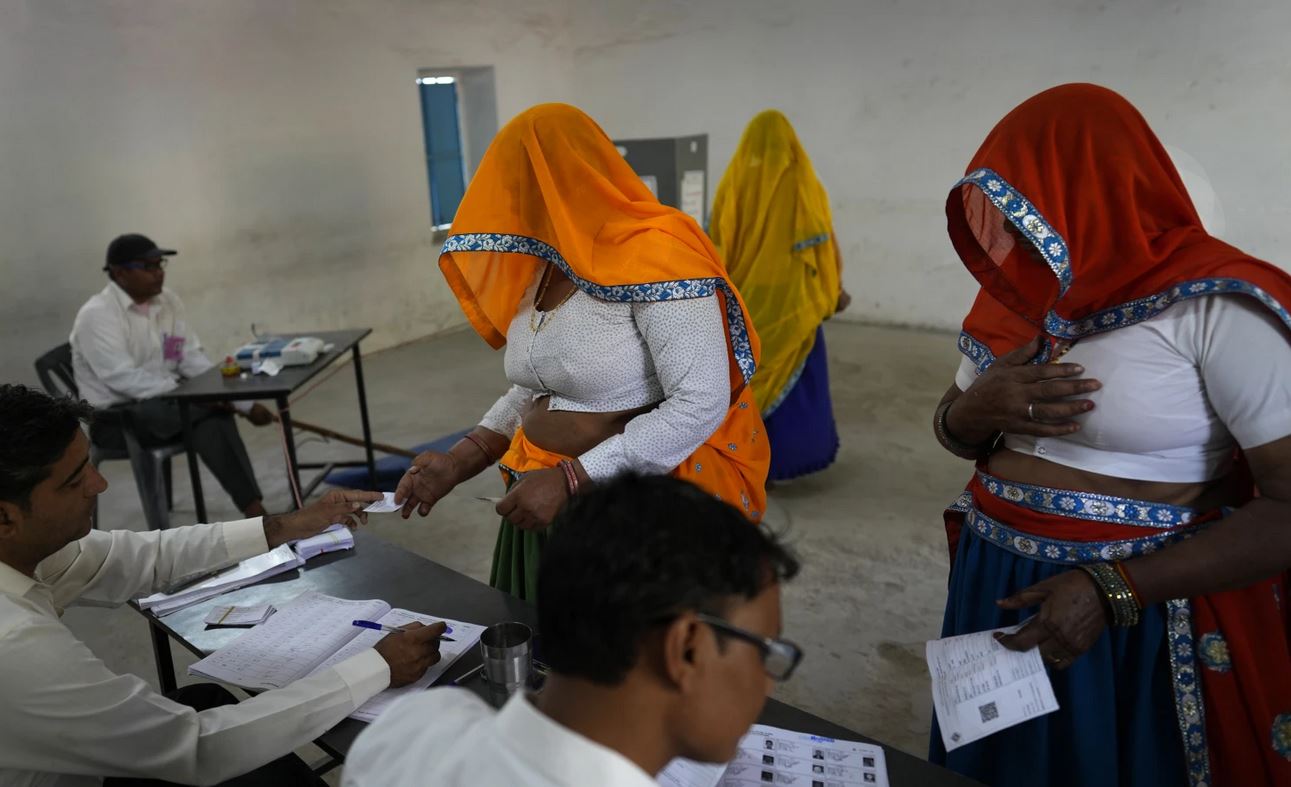

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

- 352 climbers obtain permits to ascend Mount Everest this season

- 16 candidates shortlisted for CEO position at Nepal Tourism Board

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment