OR

Monsoon rain is a lifeline to an agriculture-based economy like Nepal, where with poor irrigation system farmers have to rely on the mercy of the sky

Back in school, we had two books to read for Geography course in grade ten. One was a regular ‘text book’ on geography. The second was titled ‘Monsoon Asia.’ Such was the emphasis given on the topic of monsoon that the curriculum committee guys thought that a chapter on monsoon in the regular geography textbook was not enough and so they endorsed a separate book on monsoon.

Now as a grown up person, having left the innocent walls of the classroom long time back and witnessed the ways of the world in a bitter-sweet way, the topic of monsoon still fascinates me as much as it used to when our geography teacher made us flip through the glossy pages of the monsoon book.

As I peer through the little window of my modest New Delhi apartment every morning when I get up to check if the dark clouds have arrived bringing cool soothing rain, the sky appears clear, blue and stubborn as ever showing no respite as the mercury touches a merciless 47 degree Celsius in June. This makes me crave for monsoon much like an anxious child crying for his lost mother in the crowd.

The word ‘monsoon’ has been derived from the Arabic word mausim which means season. When summer approaches in the northern hemisphere above the equator, both land and ocean get heated. But land gets heated faster than sea and as a result the hot air above land expands and rises up creating a low pressure area. The relatively less heated sea has cooler air with higher pressure which rushes inland carrying moisture.

This phenomenon happens in the Indian Ocean area hence the ‘monsoon’ is officially known as the south-west monsoon. The first land mass to receive the monsoon clouds is Sri Lanka and the southern tip of peninsular India at the start of June.

Due to geographical terrain of peninsular India, the advancing south-west monsoon from Indian Ocean gets bifurcated into Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal branches. The former progresses into western coast of India, gathering even more moisture over the Bay of Bengal hits Bangladesh and then enters Jhapa district of Nepal by the second week of June. Then after five or six days the advancing monsoon enters the Kathmandu Valley.

As a child, I remember the monsoon rains entering the valley quietly on a dark, cloudy night and the only signal that it gave was the gentle pattering of water drops hitting slender corn leaves in our backyard. The soothing nocturnal sound was a perfect sleep inducer even to the worst of insomniacs.

The other factor that plays along with monsoon is the lofty Himalayas up in the north. They act like a blocking wall to the advancing moisture laden cloud. The monsoon cannot enter Tibetan plateau and proceed on to central Asia.

It accumulates on the windward side of the Himalayas hence places like Pokhara Valley has one of the highest rainfalls in Nepal. However the leeward side in Mustang and most parts of Tibet is barren cold desert.

In fact, Cherapunji in Meghalaya also lying on the windward side of the Himalayan range has highest rainfall on the planet. This Indian state has been aptly named as ‘cloud’s abode’—megh denoting cloud and alaya meaning abode or home.

The monsoon rain is a lifeline to an agriculture-based economy like Nepal, where with poor irrigation system, helpless farmers have to rely completely on the mercy of the sky. When seeds are sown, it is a gamble with the rains whether the farmer has a good harvest or a disastrous yield. The former President of India, Pranab Mukherjee while he was finance minister in cabinet had once remarked that ‘the monsoon is the real finance minister of the country’. Such is the impact of rain seen on the GDP growth of an agrarian country for any fiscal year.

Monsoon and economy

But the monsoon plays cruel tricks on farmers and meteorologists alike. Due to climate change, the pattern of monsoon over the years has become erratic and disproportionate.

In a large country like India, there has been heavy rain in some parts of the country while other regions have received scanty rain. This pattern has resulted in flooding in the plains with loss of lives and crops. At the same time flash floods, deadly landslides occur in the hills and mountains. Some parts receive late and deficient monsoon resulting in drought with disastrous crop yield. This has resulted in farmers committing suicides and rural folks migrating to cities adding burden to thinly stretched urban infrastructure.

The monsoon also brings mangoes, the ‘king of fruits’ on vendor carts in bustling markets. It is always interesting to ask questions about this fascinating fruit to vendors on the streets.

Much before the arrival of monsoon, sometime in late April, one can see alphonso variety from Mumbai which is one of the most expensive mangoes available. Then as the days go by one can see yellow pyramids of safeda arriving followed by sindhuri and then kesari. Later on, mellow tasting duseri hits the carts accompanied by totapuri. When the rains mature in July, one can see green but still ripe langra best grown in Varanasi and then malda and chaunsa. Toward the end of summer in August comes the big, green kalkatiya variety. When mangoes disappear from vendor’s cart at the end of summer, the mango connoisseur has to face a brief withdrawal hangover and then patiently wait until the next monsoon.

The monsoon has also been an integral part of our culture and folklore since ages. During the month of Asar, farmers have rice planting ceremony and ropai jatra in festive spirit. Many songs and poems have been written inspired by the rains and lush greenery in our hills and villages.

Rain and shine

I love escaping from clustered city houses in the valley and strolling along fields outside Kathmandu. You can smell the rains and damp earth hitting your nostrils, the sound of slush and wet mud beneath your feet as you walk in mounds demarcating paddy fields. The croaking of frogs in dark wet bushes. The cicadas crying loudly to compete with frogs. These are the memories of monsoon so vividly ingrained in my mind since early years.

Like any beginning has its end, the monsoon also retreats around September. The subcontinent’s land mass cools down as the sun heads toward south. This creates cold air from the Himalayas heading toward warmer areas in Indian Ocean. This retreating wind also known as ‘north easterly’ wind is the winter monsoon occurring from October to December. This breeze going from the cooler north to warmer southern India and then toward low pressure hot areas in Indian ocean gives rainfall to peninsular India, parts of Sri Lanka and even as far away places as Indonesia and Australia.

Thus after many months stretching from June to December and the clouds having travelled for tens of thousands of miles across oceans, plains and mountains, the cyclic journey of this phenomenon called ‘monsoon’ comes to a close. But when the next summer arrives and the land mass starts heating up again sometime in May the clouds build up over the oceans to start their journey for one more time.

And this nature’s wonder has been happening every year for millions and millions of years even before we were here on this planet.

The author is a Nepali doctor living and training in New Delhi at the moment

You May Like This

Saving Kathmandu

The houses and structures which have blocked rajkulos and canals should be shifted elsewhere ... Read More...

Going electric

Nepal should aim for promoting electric vehicle technology. Strategic approach should be adopted to formulate policies to encourage people to... Read More...

Reimagining leadership

Transitional justice process has not come to a meaningful end because conflict victims were not placed at the center ... Read More...

Just In

- Rainbow tourism int'l conference kicks off

- Over 200,000 devotees throng Maha Kumbha Mela at Barahakshetra

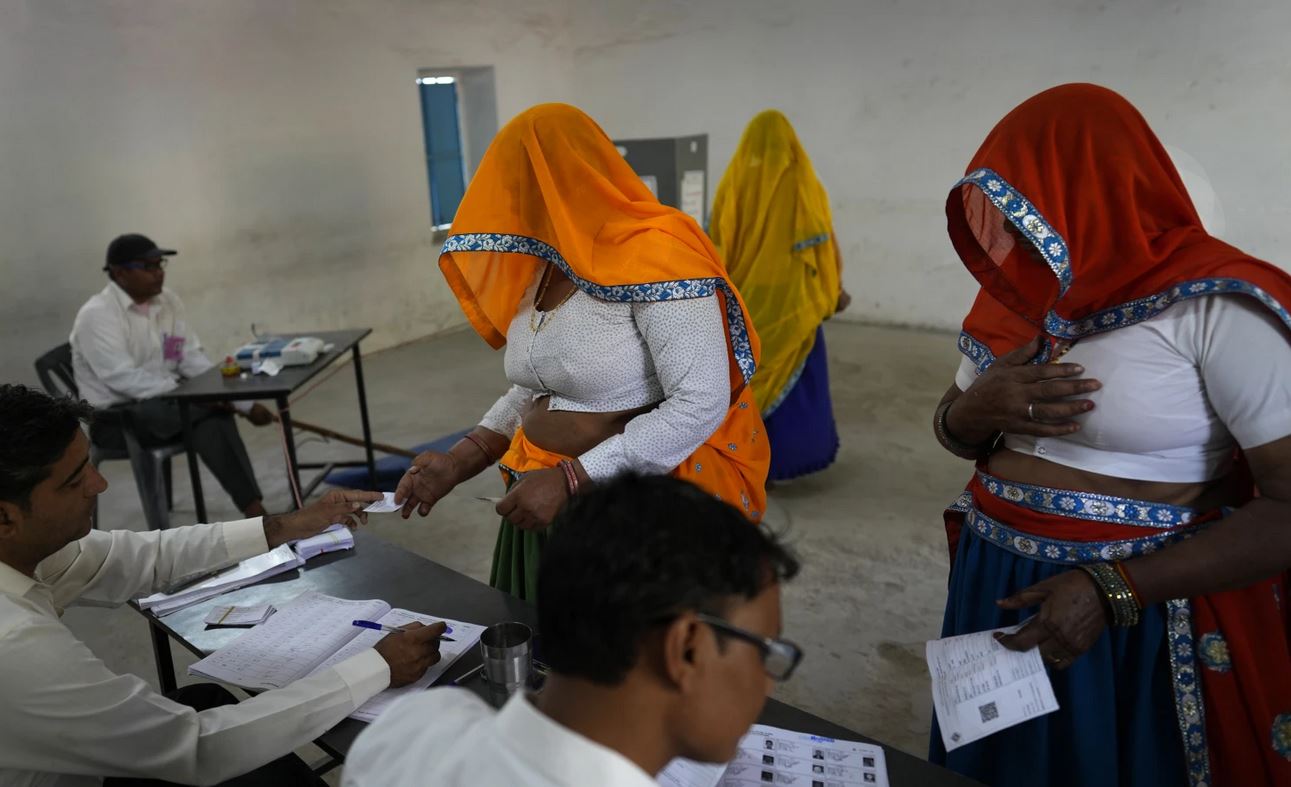

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment