OR

Biswas Baral

Biswas Baral has been associated with Republica national daily as a journalist since 2011. He oversees the op-ed pages of Republica and writes and reports on Nepal's foreign affairs. He is a regular contributor to The Wire (India).biswas.baral@myrepublica.com

More from Author

Many Nepalis wrongly believe the 1950 treaty or the subsequent Letters of Exchange accompanying it provided for open border

That the 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship and subsequent Letters of Exchange between Nepal and India have flaws is beyond doubt. India back then didn’t see Nepal as a completely sovereign country. That is why India chose CPN Singh, its ambassador to Nepal at the time, as its plenipotentiary to sign the treaty on its behalf. The natural choice would have been Jawaharlal Nehru, the Indian prime minister, since signing on Nepal’s behalf was his Nepali counterpart, Mohan Sumsher. By making Singh sign such an important bilateral treaty, the newly independent India wanted to convey that like the erstwhile British rulers it also saw Nepal as its extended appendage.

Sumsher and his fellow Rana oligarchs believed that by drafting a treaty to India’s liking they could somehow extend their rule with India’s blessings, even in the new democratic dispensation. They thus agreed to such a humiliating breach of protocol. It was interesting that a treaty of such import for the newly democratic Nepal should have been negotiated by the last holdout of the autocratic Rana regime. But, curiously, while India was hinting of Nepal’s partial sovereignty, the treaty itself clearly spelled out that “the two Governments agree mutually to acknowledge and respect the complete sovereignty, territorial integrity and independence of each other.”

Nepal’s chief negotiator with India at the time, Bijay Sumsher—Mohan Sumsher’s youngest son who headed Munshikhana, or Nepal’s de facto Foreign Ministry—deserves some credit for this. He was a consummate negotiator and even as he wanted to save the Ranarchy, he was also keen to secure the best possible terms for Nepal. It helped that India was jittery following China’s alarming push into Tibet under Mao Zedong. India feared that if it didn’t promptly bring Nepal to its side—even if it meant formally recognizing Nepal as a completely sovereign country—China would, in due course, gobble up Nepal as well.

This is the background in which the 1950 treaty was signed. But since the day of its signing, it has been controversial, and not just because of the vast difference in ranks of the two signatories. There were some iffy provisions too. According to the treaty, “the Governments of India and Nepal agree to grant, on a reciprocal basis, to the nationals of one country in the territories of the other the same privileges in the matter of residence, ownership of property, participation in trade and commerce, movement and other privileges of a similar nature.”

The most controversial aspect of this provision was related to property ownership. If every single one of around 30 million Nepalis owns a piece of land in India, they will only be able to occupy a small part of India. But if even a fraction of India’s billion-plus people own lands in Nepal, there will be nothing left for Nepalis. This provision can be operational, in the reckoning of many Nepalis, only if Nepal became a part of India.

Two minds

But precisely because many of these mutually-agreed provisions have been inoperative, there are many in India who believe the 1950 treaty has become outdated. Yes, it is not just Nepalis who want it altered, if not ditched outright.

This includes a section of the Indian security establishment. They feel that free movement of people has made it easy for anti-India elements, most notably the Pakistani military intelligence wing, the ISI, to work against India by using Nepal as their base. They also chaff at the provision in the 1950 treaty that allows Nepal to import arms and ammunitions from India (a provision that in a latter set of Letters of Exchange was tweaked to imply that Nepal could import arms and ammunitions only from India). Why should India, these Indian skeptics of the 1950 treaty ask, continue to supply arms to Nepal when it continues to discriminate against Indians in Nepal and seems increasingly keen on China?

It was Nehru who first defined the Himalayas as the “magnificent frontiers” of India. “We cannot allow that barrier to be penetrated, because it is also the principal barrier to India,” he told the Indian parliament in 1950. There is still a big section in the Indian establishment that holds fast to this old characterization and is thus uncomfortable with China extending its reach in Nepal. But there is now also growing realization that this characterization of the Himalayas as India’s frontiers is an insufficient, if not an erroneous, idea.

As KV Rajan, former Indian ambassador to Nepal (1995-2000), wrote in The Hindu sometime back: “The Himalayas have been replaced by the open border as India’s main defense perimeter.” In the same article he highlighted the need for some kind of “regulation of the open border” in light of the anti-India activities on Nepali soil. For the likes of Rajan, Pakistan, not China, is their main bug-bear in Nepal.

Always open

Many Nepalis wrongly believe the 1950 treaty and the subsequent Letters of Exchange provided for open border between the two countries.

In fact, there has been extensive movement of people through what today constitute India-Nepal borders since ancient times. The British decided not to obstruct the free movement of people after the signing of the Treaty of Sugauli in 1816, when the two countries first decided to draw a de facto border between them. Later-day British rulers also left the borders open since such openness facilitated easy movement of the Gurkha recruits in their armies and since Nepal was their main trade route with Tibet before the opening of Sikkim in early 20th century.

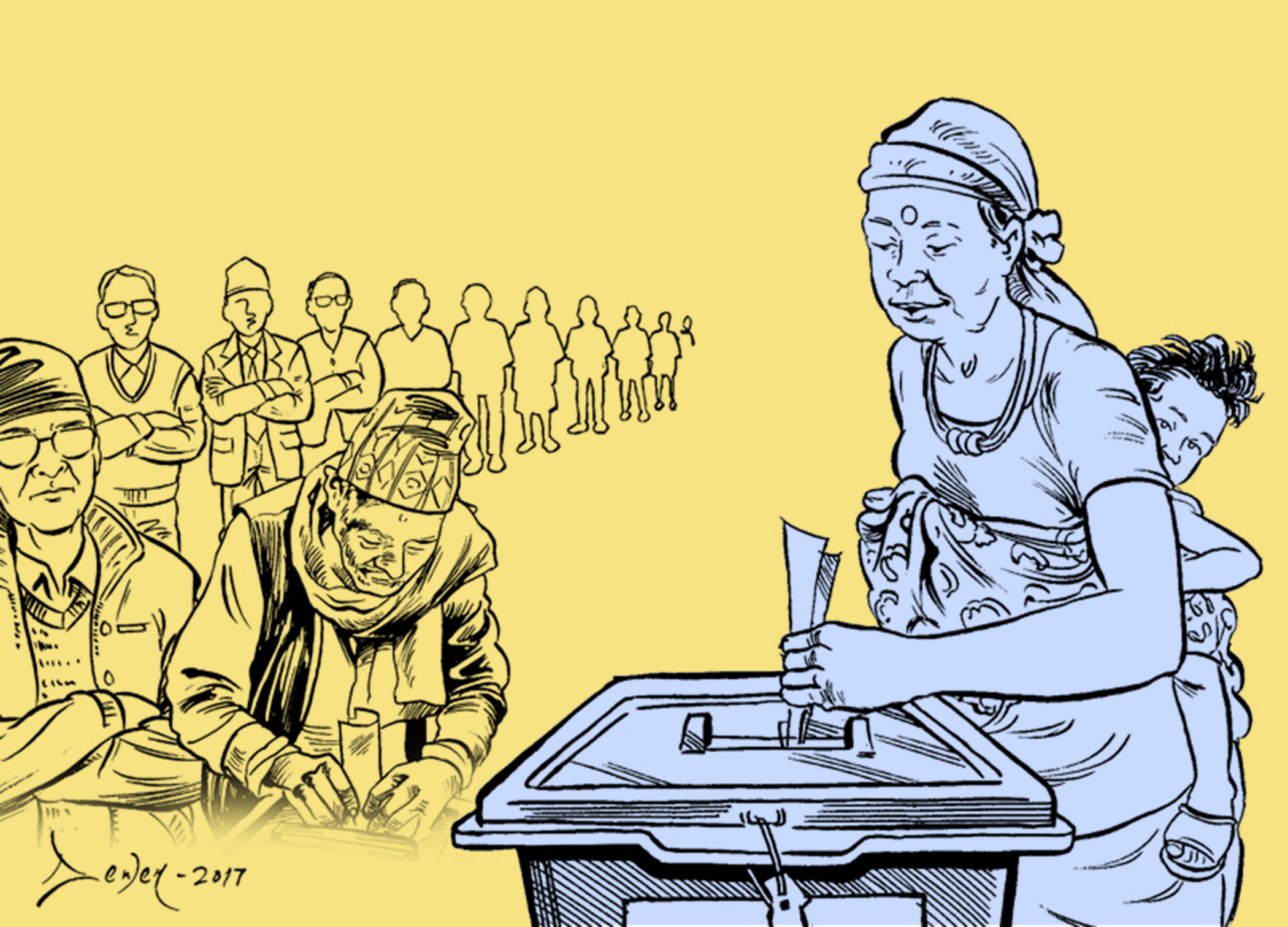

So when Nepal is now asking for a revision of the 1950 treaty, it must first be clear about what it truly wants. Following the most recent Indian border blockade, the third since 1969, there have been growing calls for regulation of the open border, for diversifying Nepal’s trade away from India, for invocation of Nepal’s right as a landlocked country to import goods unhindered. Nepal, apparently, wants to be treated like a completely sovereign and independent country once again.

This is not as straightforward as some would have us believe. If we start regulating the open border, what will be its implications for millions of Nepalis now living and working in India? Will such regulations be acceptable to the Madheshis —constituting around 36 percent of national population—who share roti-beti relations with those across the border?

If Nepal wants to import arms from other countries, can these countries commit to adequate long-term supply? Also, we no doubt need to expand into China. But will China, even if it is willing, be able to substitute in the long run the kinds of goods of daily use we import from India?

The existing treaties between Nepal and India have myriad flaws. But they have also provided a basis for largely stable, if at times testy, bilateral relations over the past six and a half decades. If we are to replace them, it should be done only after Nepal is able to clearly define its national interests in the changed political context and work out its long-term foreign policy priorities. One thing is for sure: Whatever our terms of engagement with the rest of the world, including China, picking needless battles with India will take us absolutely nowhere.

Twitter: @biswasktm

You May Like This

Equidistance revisited

Equidistance indicates maneuvering of small states like Nepal while dealing with big powers like India and China ... Read More...

Resolutions revisited

Every year, come December 31, I sit to write down my New Year resolutions for the coming year. The first... Read More...

Tikapur revisited

Those who masterminded the attack that led to the henious killings of eight unarmed policemen are walking free with political... Read More...

Just In

- World Malaria Day: Foreign returnees more susceptible to the vector-borne disease

- MoEST seeks EC’s help in identifying teachers linked to political parties

- 70 community and national forests affected by fire in Parbat till Wednesday

- NEPSE loses 3.24 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.36 billion

- Pak Embassy awards scholarships to 180 Nepali students

- President Paudel approves mobilization of army personnel for by-elections security

- Bhajang and Ilam by-elections: 69 polling stations classified as ‘highly sensitive’

- Karnali CM Kandel secures vote of confidence

Leave A Comment