OR

U.S.-led coalition killed 1,600 civilians in Raqqa, says Amnesty International

Published On: April 26, 2019 08:00 PM NPT By: Associated Press

BEIRUT, April 26: The U.S.-led coalition killed more than 1,600 civilians in the northern Syria city of Raqqa during months of bombardment that liberated it from the Islamic State group, hundreds more than the number the U.S.-led coalition claims over the entire four-year campaign against IS, Amnesty International and a London-based watchdog group said Thursday.

Amnesty and Airwars said the toll came after the “most comprehensive investigation into civilian deaths in a modern conflict.”

The U.S.-led coalition said last month that 1,257 civilians were killed in airstrikes against IS over four years in Syria and Iraq.

“We continue to employ thorough and deliberate targeting and strike processes to minimize the impact of our operations on civilian populations and infrastructure,” the coalition said.

Raqqa was the de facto capital of IS’s self-declared caliphate, which once encompassed a third of Syria and Iraq. Last month, IS lost the last area it controlled in eastern Syria marking the end of the so-called caliphate.

U.S.-backed Syrian fighters captured Raqqa in October 2017 after a four-month campaign.

The U.N estimates that more than 10,000 buildings were destroyed or 80 percent of the city.

“Coalition forces razed Raqqa, but they cannot erase the truth. Amnesty International and Airwars call upon the Coalition forces to end their denial about the shocking scale of civilian deaths and destruction caused by their offensive in Raqqa,” the two groups said in a joint statement.

In June last year, an Amnesty International report said hundreds of civilians were killed in Raqqa, while the Airwars said it has evidence of 1,400 fatalities.

The statement said Amnesty International’s innovative “Strike Trackers” project also identified when each of the more than 11,000 destroyed buildings in Raqqa was hit. More than 3,000 digital activists in 124 countries took part, analyzing a total of more than 2 million satellite image frames, it said.

“The Coalition needs to fully investigate what went wrong at Raqqa and learn from those lessons, to prevent inflicting such tremendous suffering on civilians caught in future military operations,” said Chris Woods, Director of Airwars.

Separately, Syrian Minister of Transportation Ali Hammoud said his country will sign a contract with a Russian company to run and expand the port of Tartous on the Mediterranean.

Hammoud said in remarks published by the pro-government Al-Watan daily Thursday that Russia’s Stroytransgaz will run the port for 49 years. The minister added that a Russian company would expand the port and pump more than $500 million in this project, pointing that it has been agreed with the company to keep all Syrian workers in the port.

Russia has been a main backer of Syrian President Bashar Assad’s government and Moscow tipped the balance of power in favor of government forces after joining Syria’s war in 2015.

Russian Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Borisov met with Assad in Damascus over the weekend and said in comments carried by Russian news agencies that he was expecting the contract to be signed this week.

Borisov said the Russian lease of the port would boost bilateral trade and benefit the Syrian economy.

Stroytransgaz is controlled by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s childhood friend Gennady Timchenko. The Tartous port would be an important asset for the company which landed a contract for 30 percent of the output in a major phosphate field outside Palmyra last year and signed a deal with a government-owned chemical company to rebuild Syria’s only fertilizer plant in the central province of Homs.

Unlike many major Russian companies, private or state-owned, Stroytransgaz is not wary of international sanctions against the Syrian government since Timchenko himself and his businesses including Stroytransgaz were slapped with U.S. sanctions in 2014 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

You May Like This

Iraq: American troops leaving Syria cannot stay in Iraq

BAGHDAD, Oct 22: U.S. troops leaving Syria and heading to neighboring Iraq do not have permission to stay in the... Read More...

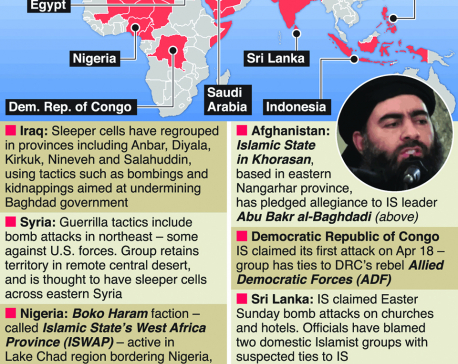

Infographics: So-called Islamic State still a threat in many countries

After the defeat of the “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria, the so-called Islamic State group still poses a security threat... Read More...

Islamic State acting as US "ally" for regime change in Syria, suggests Lavrov

LISBON, November 24: The Islamic State terrorist organization (outlawed in Russia) is allied with Washington, in carrying out the objective... Read More...

Just In

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

- Court extends detention of Dipesh Pun after his failure to submit bail amount

- G Motors unveils Skywell Premium Luxury EV SUV with 620 km range

- Speaker Ghimire administers oath of office and Secrecy to JSP lawmaker Khan

- In Pictures: Families of Nepalis in Russian Army begin hunger strike

- New book by Ambassador K V Rajan and Atul K Thakur explores complexities of India-Nepal relations

- Health ministry warns of taking action against individuals circulating misleading advertisements about health insurance

_20240419161455.jpg)

Leave A Comment