OR

More from Author

Universities should have structures dedicated to connecting with their potential partners in the community, government, industries, foundations, and so on

Universities can and should emerge as the forerunners of national development. However, this requires a substantial revisit of our understanding and approach to higher education. Obviously, universities need to respond to changing times. The world today is moving and morphing at a dizzying speed, especially given the rapid changes in technology and communication. The boundaries between disciplines are blurring and new fields are emerging before our eyes.

Terms that were unknown even a decade ago are now buzz words. Everything is changing: the way we study; the way we seek information; the way we gather knowledge; the way we communicate; the way we manage people and organizations; and the way we think about future. However, there is still a major lag in how we in education address these changes. As universities, we should not only catch up with these transformations. We should be leading them.

Lead the change

First, we need to develop and tailor academic programs that suit these new and relevant themes to make them more contextual. We must be innovative and also nimble enough to designing new programs and not simply hold onto our old, conventional programs. At Kathmandu University, for example, we can point with some pride to recently-developed programs in mountain architecture, sustainable development, global health and ethno-musicology.

Whenever we talk about these new, previously-unheard-of disciplines, people ask us about their scope. They wonder whether graduates will get jobs after their education, if there is risk to their careers, and so on.

Those who ask such questions may be missing the point. I do not believe that developing programs only in the areas that have ironclad, guaranteed employment scope is the correct approach. Academic institutions should do more than simply walk on the roads that already exist. We should be creating new avenues where thousands others will tread.

Let us set new trends, rather than just following set-trends. Let us explore new horizons, rather than cozily settling with the comfortable past. Our past successes do not guarantee future success. Let us take small, but courageous steps into unchartered territories rather than just standing on the established foundations. These first steps will be the stepping stones for larger victories. As the famous artist Vincent van Gogh said, ‘Great things are not done by impulse, but by a series of small things brought together.’

This sort of experiment requires an environment and administrative mechanisms that welcome emerging professionals and youths. It requires simplified and easier processes within the university so that we can create new programs, centers and institutes.

An administration that is built with the fabric of complex hierarchies and complicated bureaucracies will crumble under its own weight. In an effort to avoid risks, let us not restrict the need to experiment. In an age where people in their twenties and thirties are creating history in innovation, we need to create a system to support, nurture and promote young minds. In the context of Nepal, this also means creating platforms for the engagement of the Nepali diaspora, our alumni and other interested professionals. This year Kathmandu University will convene a special meeting of Nepali diaspora professionals to specifically explore how their expertise can be harnessed to strengthen academia in Nepal.

Second, collaborative mechanisms between universities and other non-university institutions must be more flexible. If every field is connected to academia in some way, why is there still so much disconnect between and among them?

If universities are the engines for national development, we should have a dedicated wing within ministries to connect with academia. Likewise, universities should have structures dedicated to connecting with their potential partners in the community, government, industries, foundations, and so on. We also need to reactivate our existing collaborations and seek new collaborations to help bring a breath of fresh air into our academic environment.

I am glad that the rapid expansion of international collaboration within KU is accelerating this pursuit. Our recent establishment of an Office for Community Engagement will also help bridge the gap.

At this age, it is no longer possible to work in single disciplinary silos. Designing academic and research consortia, strengthening complementary partnerships are the only way to move ahead. Almost all of the projects that led to scientific breakthroughs have been huge collaborative projects—be it CERN in Switzerland, the 22 country-led European Organization for Nuclear Research, or the multinational International Space Station.

Together we grow

KU has forged alliances with several other key organizations. Consider our recent partnership with Khopasi Hydropower, which serves as a wet-lab for engineering students; or our music department at Tripurasundari temple; or our partnership with the Institute for Integrated Development Studies (IIDS) for policy studies; or our School of Medical Sciences’ large and growing network of rural health and community development programs. These are just a few examples.

Through the recent establishment of Nepal Technology Innovation Center (NTIC), Kathmandu University aims to provide additional catalytic support to our students, faculties and staffs in harnessing the strengths of a multi-disciplinary and multi-sectorial approach to academia, research and development. We will continue to create new entities within our institution and build new modalities of partnerships to fulfill our mission and preserve our values.

Let us widen the scope of our university beyond the boundaries of our buildings, to the larger community. We must not wait for opportunities to come to us, but rather proactively seek, create and hold them. This has been my own professional and personal experience as well as a firm belief.

Third and most importantly, we must categorically reject mediocrity. Accepting mediocre achievements has far more detrimental impacts than we may assume. Mediocrity hinders sustainability because it does not generate attention, respect or trust. Mediocrity consumes, rather than creates its own resources. Excellence, on the other hand, may appear to require more resources, but in the long run, excellence sustains itself. A small diamond fetches more than a heap of rocks. For a product as trivial as a knife, Switzerland created a brand of a Swiss-knife. For a product as common as chocolate, Switzerland built an empire of Swiss chocolates. Commitment to quality requires relentless determination, dedication and perseverance.

I reject the notion that we are not able to produce high-quality programs because we lack resources. On the contrary, I think, we are oblivious to, or ignore the resources we already have. What stops us from creating world-class educational and research programs in areas that are unique to us? I see opportunities everywhere.

I see no reasons why Nepal can’t be the world’s premier destination to learn about tourism and hospitality management, hydropower development, Buddhist studies, natural resource management, community engagement in governance, and so on. However, we need to build gem-like, high-quality programs of unparalleled excellence and uniqueness. Only then will the world follow us. The identity, the status and the category of a university is defined by nothing else but by the quality of its programs, the changes it brings to the society, and the commitment demonstrated by its members.

Let us challenge our thoughts, critique our beliefs and argue against our ideas, but all in constructive ways. We have to stand together to fight against the maladies of the society. Our biggest rivalries should be with the forces that hinder our nation’s development, with the ignorance that ditches opportunities, with the inertia that refuses change. We are the architects of the new educational revolution.

The author is Vice Chancellor of Kathmandu University

You May Like This

UML leader Basnet to Balen: Don't be pampered just because you have a few hundred fans on Facebook

KATHMANDU, August 26: While the Mayor of Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC), Balendra Shah, is speeding up the work to demolish... Read More...

Transformation in teaching

For realizing the changes, our universities must shift some weight of teaching to learning, knowledge to skills, exams to... Read More...

NUTA seeks recognition of central-level universities to state- owned universities

KATHMANDU, June 20: A delegation from the Nepal University Teachers' Association (NUTA) today called on Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba... Read More...

Just In

- Sudurpaschim: Unified Socialist leader Sodari stakes claim to CM post

- ED attaches Raj Kundra’s properties worth Rs 97.79 crore in Bitcoin investment fraud case

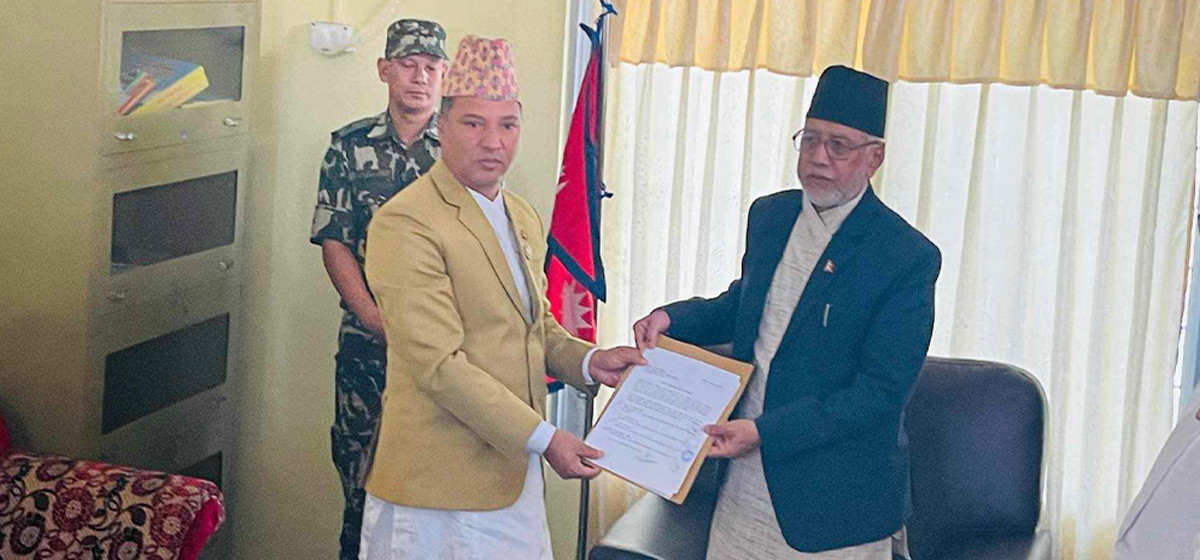

- Newly-appointed Auditor General Raya takes oath

- CM Mahara expands Cabinet in Lumbini Province

- FinMin Pun addresses V-20 meeting: ‘Nepal plays a minimal role in climate change, so it should get compensation’

- Nepalis living illegally in Kuwait can return home by June 17 without facing penalties

- 'Trishuli Villa' operationalized with Rs 100 million investment

- Unified Socialist rejoins Lumbini Province govt following ministry allocation

Leave A Comment