OR

Credibility gap

More from Author

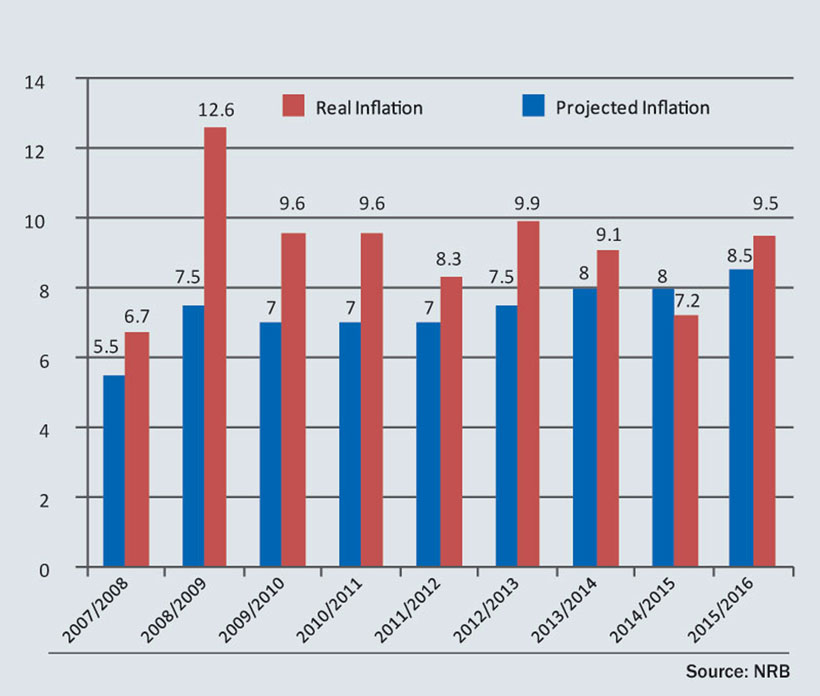

In the last fiscal year inflation soared to 9.9 percent, the highest in seven years, and 1.5 percentage points above the set target

Once again Nepal’s monetary authority, Nepal Rastra Bank, missed the inflation target it had set for the last fiscal year. No wonder. In the past 13 fiscal years, the central bank has achieved its annual inflation target only twice. The last fiscal remained no different as inflation soared to 9.9 percent, the highest in seven years, and 1.5 percentage points above the target. More than that, the difference in inflation between Nepal and India widened to 4.7 percentage points, much higher than normal average but less than the record difference seen in the previous year.

Of course, the monetary authority, as usual, comes up with plenty of reasons to defend its failure to keep the inflation within the desired level. Top on the list for the past year, as we all know, was the five-month-long trade blockade that paralyzed supplies and swelled prices. But even months after restoration of normal supplies, there is virtually no reversal of the prices that soared during the blockade.

In fact, inflation in Nepal is a one-way traffic; it goes up when there are obvious reasons but doesn’t come down when abnormalities are gone. For instance, restaurants throughout the country increased prices of all kind of foods during the blockade; understandably, as they were compelled to buy cooking gas and other stuff in black-market. But the menu prices never went down when market supplies returned to normal.

Another example is the prices of lubricants in the local market. When the international crude oil price spiked to record US $136 per barrel in June 2008, the prices of the lubricants soared worldwide and also in the domestic market. Now, when the prices of petroleum products are at record low, hovering around $45 per barrel, the prices are still the same.

Now the fundamental question is: Why is the domestic consumer market not operating according to the principles of liberal and open market economy based on demand and supply? Why doesn’t the market behave in a rational manner despite the presence of plenty of buyers and sellers? For example, why don’t sellers lower their prices so that they eventually get more business and profit? And why don’t buyers resist unseasonal price rise or seek alternatives, an obvious way to check general increase in prices?

There are basically three reasons. The first is continued remittance-fired robust demand. As a result, consumption expenditure—the portion of total income that is used in purchasing goods and services—has increased over three folds in the past one decade. Surprisingly, average annual growth rate of consumption expenditure, which is also the total demand, was 13.7 percent in the past decade. In absence of domestic supplies, such an exponential growth in demand fueled imports, which on average grew by 16.5 percent over the past decade. These statistics clearly show that remittance-driven demand is a key factor for high inflation.

The second is high inflation expectation. Given that Nepal has remained a high inflation country—averaging 9 percent over the past decade—consumers, businesses and investors expect that prices will continue to increase in the near future. Businesses and consumers have lost hope that monetary authority and state machinery have the ability to decisively act to check unseasonal price maneuvering.

As a result, high inflation expectation is unnaturally propping up demand because consumers are buying everything that they need in near future so that they don’t have to pay more in the future. For example, we see consumers buy two/three sacks of rice as festivals approach, even though the actual demand may be hardly a sack for next few months. In any economy, moderate inflation is desired for healthy demand but high inflation expectation is bad as it makes consumers hoard goods that in turn increases demand unnaturally and propels prices.

So what is the solution then? Recent Indian experiments in dealing with high inflation expectation have produced impressive outcomes. Indian economy, which had a long history of high inflation expectation, has lately been successful in taming it by adopting inflation targeting monetary policy, a policy reform orchestrated by outgoing Indian central bank governor Raghuram Rajan.

The policy that sets inflation target of 4 percent with a range of plus/minus 2 percent for the five years, has been able to bring down retail inflation to half the level from its recent pick of 10 percent (in FY 2013). But how does inflation targeting monetary policy work?

The core idea is simple: the policy states that monetary authority expects inflation to remain within a certain range, such as 5 plus/minus 1.5 percent and will take decisive actions if inflation moves out of that range. Some shortcomings aside, such a mechanism helps stabilize household consumption and for businesses to gauge profitability. But an important precondition for the policy is that a country needs a credible monetary authority and effective tools that can perform.

Third and the most serious challenge is the presence of strong price collusion in each level of transaction—from importer/producer, wholesalers to retailers—something that has paralyzed natural competition. Such collusion whose sole motive is to secure unnatural profit margin has lately become so powerful it is openly defying state machineries formed to protect consumer rights and promote healthy competition.

Transport syndicates that hijack state-built roads and monopolize routes by allowing specific associations to operate public buses, is one classic example. Despite several directives by parliamentary committees and court rulings, these transport syndicates have barely budged. That is why there is no revision of transport fares despite a 33 percent decline in diesel price in the past two years. These syndicates that amassed a huge wealth by hijacking competition have now emerged as a major donor to political parties and exercise huge political influence.

Similar is the case for domestic food commodity market, which has been taken over by a handful business houses. These houses have generated unparalleled wealth and exercise control over state machineries. These houses now command enough clout to manipulate domestic food supplies by sidelining Nepal Food Corporation, a state-owned food supplier, and to build near monopoly in the food commodity market. That is why despite the presence of different brands of wheat flour and pulses, among other commodities, retail prices are almost identical. That is why prices of pulses are still at their pick, even though prices in India, which supplies these pulses to Nepal, are already declining.

Democracy without accountability and free market without functioning competition is doomed to fail, as the saying goes. It is clear that monopolists, emerging lately in the name of various commodity associations, are gradually chocking market competition and it is the most dangerous threat to the liberal economic policy that the country adopted since 1990. So inflation in Nepal is dependent on many more factors than the level of money supply that the monetary authority manipulates to keep inflation within a desired level. What we need is political willpower to combat the systematic extortion of big houses and to dismantle the supply barricades they have erected, not unrealistic monetary policies to tame inflation.

The author is a senior journalist who writes on economic issues

pk2445@columbia.edu

You May Like This

Inflation moderated to 6.83 percent last month: NRB

KATHMANDU, July 10: The consumer price inflation moderated in the eleventh month of the current fiscal year. ... Read More...

Consumer inflation eased to 5.65 percent last month: NRB

KATHMANDU, Feb 9: The consumer price inflation was recorded at 5.65 percent as of mid-January as compared to 3.56 percent of... Read More...

Dollar stumbles against majors, Aussie boosted by strong domestic job gains

Sept 16: The U.S. Dollar was pressured most of the week by a pair of weaker-than-expected inflation reports and the... Read More...

Just In

- 70 community and national forests affected by fire in Parbat till Wednesday

- NEPSE loses 3.24 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.36 billion

- Pak Embassy awards scholarships to 180 Nepali students

- President Paudel approves mobilization of army personnel for by-elections security

- Bhajang and Ilam by-elections: 69 polling stations classified as ‘highly sensitive’

- Karnali CM Kandel secures vote of confidence

- National Youth Scientists Conference to be organized in Surkhet

- Rautahat traders call for extended night market hours amid summer heat

Leave A Comment