OR

Post-partum depression is a real disease as much as diabetes, hypertension or cancer. Just because it isn’t a tangible form of illness doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist Nepal

Fifteen years ago, barely into my twenties, when I first gave birth, amidst complications, I had no idea what roller coaster of emotions I was going to be riding. After a complicated pregnancy and an emergency caesarean surgery, not a single person, including my healthcare team, had anticipated, assessed, discussed, expressed concerns or seemed to have any knowledge or awareness about post-partum depression (PPD). Needless to say, neither my obstetrician-gynaecologist (OBG) nor any health worker had prepared me for the worst to come. Few months after the delivery, I tried committing suicide only to fail at my attempt. I was chastised and labelled as being mad, a drama queen and a non-instinctual mother.

I wasn’t aware back then that what I was going through was termed as post-partum depression. There was no screening done, there were no referrals made even after my suicide attempt and no one knew why it happened (except few precipitating factors and few symptoms) and obviously there was no follow up. Unfortunately, things still haven’t changed much in Nepal even after fifteen years.

Suffering in silence

In Nepal, thousands of women give birth each day. Maternal health awareness, infant monitoring and maternity care packages have been around for a little over a decade now, yet hardly any healthcare worker including midwives, obstetrician-gynaecologist, Paediatric Active Enhanced Disease Surveillance (PAEDS) workers, nurses, social workers, etc seem to be a part of official system that actively participate in discussing awareness, identifying risks factors, providing evidenced-based information and support or involving entire family for treatment plan regarding PPD as part of prenatal checks. Maternity care packages only seem to cater interventions and awareness regarding clinical complications during pregnancy and childbirth. There is still a huge gap in preparing mothers mentally of what might lie ahead in their journey into motherhood.

After discussions with some OBGs and PAEDS consultants in Nepal, I’ve learnt, to my dismay, that psychiatric referral services have been made few and far between in countable numbers till this day. Referrals are made only when the PPD sufferer’s family comes forward to seek help for “unknown reasons” for distressed mothers. Unfortunately, by that stage, things would have gone way beyond immediate recovery, hence inducing and/or prolonging the complications of psychosis and inevitable relapses. No long term interventions or follow up system appear to be in place even now.

Fourteen years later, throughout pregnancy and just two days after my second complicated caesarean delivery, my midwife who was visiting me at my home, ensured that I filled out the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). EPDS is a score based scale used in conjunction with other clinical assessments to screen women for symptoms of emotional distress during pregnancy and post delivery in most Western countries. Lack of use of this scale in developing countries like Nepal is an indication of how mental health issues are neglected.

So what is PPD? Motherhood and its aftermath may not necessarily be a happy experience for many women. It might turn out to be an enduring responsibility based on the socialized gender role of women. A new mother goes through a lot of changes after birth. Factors such as chemical changes including, but not limited to, drop in pregnancy hormones in the body after delivery and surge of new hormones for breastfeeding may result in mood swings, being oversensitive and emotional which, if left unchecked, might lead to severe depression. Other major factors include physical changes after birth like surgical wound, scars or stretch marks in visible areas, weight gain, pigmentation marks on face, etc leaving some women feeling extremely self-conscious which might take a massive toll on their psychology and also physical health.

Other unsuspecting factors that could potentially contribute to post-partum depression in new mothers could be socialised gendered role and its expectations from a new mother such as 11 day seclusion ritual, breastfeeding pressure over bottle feeding and its sole responsibility on new mothers, nappy changes, sleepless nights due to feeding regimen, career responsibilities, social isolation or social overwhelm (incessant visitors invading privacy and sleep/feed regimen) due to traditional afterbirth rituals, lactation issues and mother-newborn bonding time issues, etc. Other factors could include pre-existing tensions in the family and relationship.

Many people dismiss PPD as new mothers’ laziness, drama and inefficiency. There is a major issue in diagnosing PPD in the context of Nepal. Recent conversations with many new mothers and some OBG and Paediatric specialists in Nepal highlighted the fact that PPD has become a burning issue in Nepal too especially due to increasing number of nuclear families and city-migration where new parents have limited social network, help, support and where there are only a few handful of specialists who are proficient in referring patients for further assessments for diagnosing PPD.

Preventing PPD

PPD is real as much as diabetes or hypertension or cancer. Just because it isn’t tangible form of illness doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist and in the context of Nepal, just because people are choosing to dismiss its existence doesn’t invalidate this illness. Not talking about the elephant in the room only makes treatment harder, deteriorating the condition and leading to a loss of a beautiful bond a mother should have shared with her newborn.

Its diagnosis is not that difficult once there are clinical measures, resources and well-trained healthcare staffs incorporated into the system. Respectful maternity care package is one such initiative where precautions, indications and risk factors of PPD could be introduced as a real measure to help prepare mothers-to-be and their family about PPD.

It’s about time we understand and support mothers going through PPD and difficult motherhood so that we can help build a society where we enable mentally strong women and their children to live without any prejudices or isolation.

The author teaches Nursing in Australian Catholic University, Sydney

You May Like This

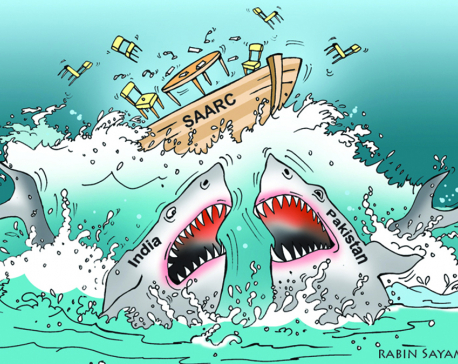

SAARC is sinking

Prospects of SAARC have shrunk further with India thinking of its alternative and alleging Pakistan for state-sponsored terrorism ... Read More...

Mom, dad, I’m coming home

I realize that home is the place to begin and go back to. I want to learn to live with... Read More...

Abolish private education?

To truly counter arguments about abolishing it, private sector education must rethink its socioeconomic roles in the new national... Read More...

Just In

- One killed in tractor-hit

- Karnali Chief Minister Kandel to seek vote of confidence today

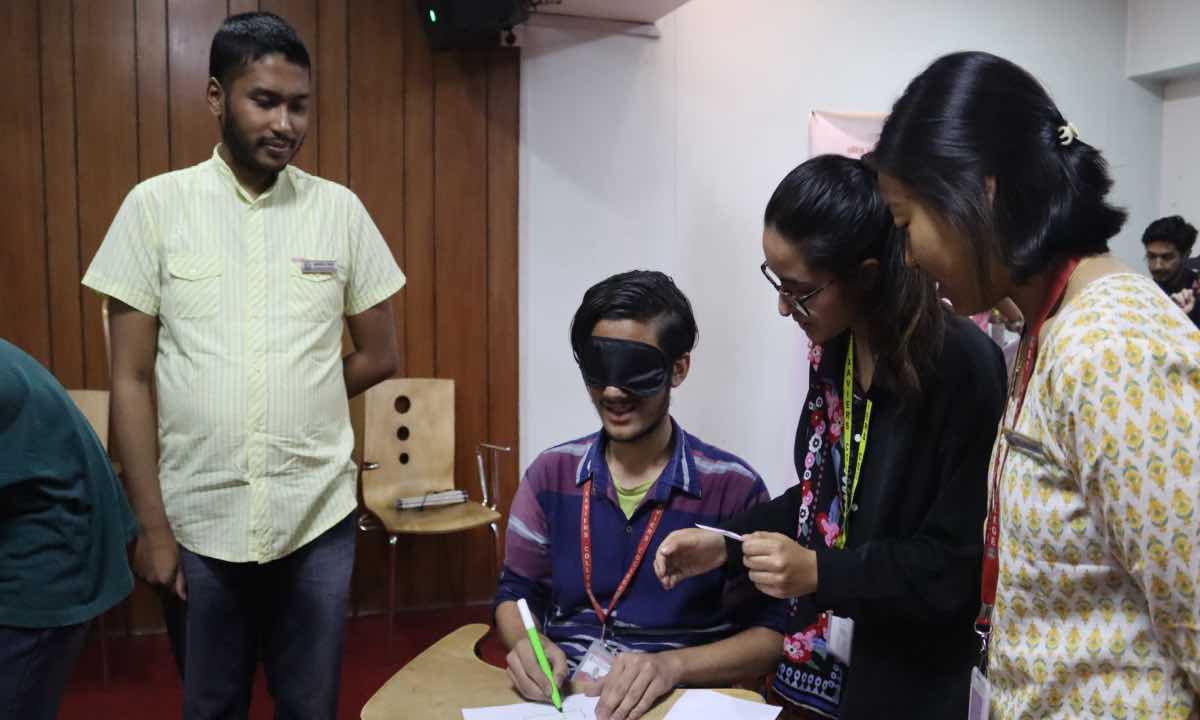

- Chain for Change organizes ‘Project Wings to Dreams’ orientation event for inclusive education

- Gold price decreases by Rs 200 per tola today

- National Development Council meeting underway

- Meeting of Industry, Commerce, Labor and Consumer Welfare Committee being held today

- Nepali announces cricket squad under captaincy of Rohit Paudel for series against West Indies 'A'

- Partly cloudy weather likely in hilly region, other parts of country to remain clear

Leave A Comment