OR

No country for new leaders

Published On: September 20, 2018 01:30 AM NPT By: THIRA L BHUSAL | @ThiraLalBhusal

THIRA L BHUSAL

Thira Lal Bhusal has been working as a journalist for over a decade. At present, he is working with Republica national daily and covers parliamentary, federalism and other political affairs. Previously he worked for various other national and international media.thirbhusal5@gmail.com

Obama became the US president 13 years after Deuba became Nepal’s prime minister in 1995. When Jhalanath Khanal became UML’s general secretary, North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un was not even born

When Jhalanath Khanal became General Secretary of the then powerful Communist Party of Nepal (Marxist-Leninist) in 1982, North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un, the world’s most talked-about leader now, wasn’t even born. BBC says Kim was born in 1983 or 1984, at least a year after Khanal’s ascension to party’s top post. Many of the heads of governments and states, who have now established themselves as influential international leaders, were kids in the early 1980s. To name a few: New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern was just one-year old, President of France Emmanuel Macron was four, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras was seven and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau 10.

Mother of three-month-old baby, Ardern is emerging as a popular leader in and outside New Zealand within a year after her election to the top post. Leftist leader Tsipras, who became the prime minister at the age of 40 when Greece was in severe economic crisis, has made significant progress toward salvaging the country from the crisis. Tsipras, Trudeau and Macron have been impressively reviving hope in their respective countries within a few years after they rose to power.

When Sher Bahadur Deuba became home minister and Ram Chandra Poudel minister for local development and agriculture in 1991, Barack Obama had just graduated from the Harvard Law School and had started working as a civil rights attorney teaching constitutional law at the University of Chicago Law School. Obama became the US president 13 years after Deuba became Nepal’s prime minister in 1995. He completed his two-term presidency as one of the most popular leaders. A 57-year-old Obama is now living a happy life with his wife, two daughters and other family members. When the world debates climate change, disaster, trade, peace, immigration and healthcare, Obama’s words are closely watched and accorded due importance. This statesman has cemented his legacy, both at home and abroad.

When Deuba became prime minister for the first time in 1995, his counterparts were PV Narasimha Rao in India and Sir John Major in the UK. Bill Clinton was president in the US and Jiang Zemin in China. After that, HD Deve Gowda, Inder Kumar Gujral, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Manmohan Singh and now Modi have become prime ministers in India. And in the UK, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and David Cameron have already completed their tenures. Since 1995, Bill Clinton, George W Bush, Barrack Obama each completed two presidential terms and bade farewell to the White House. Donald Trump is ruling the country at the moment. In China, Jiang and Hu Jintao each completed two terms and now Xi Jinping is in his second term. All these leaders have retired from active politics and living off writing books, lecturing and doing other humanitarian works.

Kamal Thapa, president of Rastriya Prajatantra Party, became minister for the first time in 1986, when Ronald Reagan was the president of the US. Thapa was just 30 then. Since then, he has remained in power—as a minister, lawmaker, opposition leader, party chief or in whatever capacity for the last 32 years. Thapa, who now champions constitutional monarchy and Hindu Kingdom, became the minister during party-less Panchayat system in 1980s, under multiparty democracy with constitutional monarchy after the 1990s, during King Gyanendra’s direct rule and in secular republic as well.

These are just a few comparative examples which show how political leadership has changed in Asia and beyond while the same set of leaders are at the helm in Nepal. These countries have progressed because their politics, economy and bureaucracy function based on certain written or unwritten policies, principles and practices. And they rarely deviate from those norms.

Stick to power, Nepali way

Only two leaders after the restoration of democracy in 1990 have stood as exceptions to this entrenched rule of ‘stick to power.’ Ganeshman Singh and Madan Bhandari established their own unique image in Nepali politics without holding top post like prime minister or president. Singh and Bhandari are probably the two most-revered Nepali leaders since 1990. Singh refused the offer of prime minister from King Birendra upon the success of people’s movement in 1990 while Bhandari never held ministerial post, let alone becoming the prime minister. Singh also never became chief of the party. At 42 and within years after he became the communist party’s general secretary, Bhandari propounded a new political thought to transform his party as a democratic force.

After Bhandari’s death in 1993, his comrades Manmohan Adhikari, Madhav Kumar Nepal, Jhalanath Khanal and KP Sharma Oli led the party and government in different periods. Nepal became deputy prime minister with foreign and defense portfolio while Oli became home minister in Adhikari’s government in 1994. After three years, Bamdev Gautam became home minister in a coalition government. These leaders have been in power since then.

Elsewhere when a popular leader loses elections, they accept people’s verdict and devote the rest of their lives championing the cause they believe in. For instance, after then vice president Al Gore lost presidential election to George W Bush in a slim margin in 2000, he started working on climate change issues and retired from active politics. In 2007, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his contribution in making climate change a global issue.

Jimmy Carter, who lost second term to Republican candidate Ronald Regan, was 57 at the time of his exit from the White House. Later, he founded The Carter Center and worked worldwide in the field of peace and democracy. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002.

Like Gore, Carter, UK’s Tony Blair and various leaders after completing their official position have been actively working through their foundations. Leaders like George HW Bush, his son George W Bush, Clinton, Blair and Chinese president Hu are still active but are not active in politics. Xi has indicated that he might remain for longer in power and that has not gone well within the Chinese leadership because that goes against the system China has been adhering for many years.

In Nepal, the problem of leadership handover has remained a perpetual problem right since political parties like Nepali Congress and Communist Party were established back in the 50s. Two recent developments have made it more pertinent this time. First, the NCP has decided to omit the 70-year-age limit for retirement of its leaders and secondly, its leaders are now working to hold by-election in Dolpa or any other district to elect Gautam in the federal parliament. He had lost the election last year. The age limit provision to hold an executive post in the party was removed at the time of merger of UML and Maoist Center. At the time, Gautam was on record saying that the provision was removed because it was included with a bad intention against him. Nepal, Dahal and Oli are in their late 60s while Gautam is already 70. And they rule for perpetuity in parties and politics in Nepal because they face no real challenge from their juniors.

Under old men’s shadow

The second-rung leaders think their future is secure under “the patronage of a big leader” instead of raising voice against hegemony of the old. They failed to unite and raise voice against the top leaders’ decision to omit the age limit provision.

The tendency of letting the old men rule infinitely runs across all party lines. This national disease is not just limited to NCP, NC or RPP. Top positions of all political parties are captured by the same old faces. Think of it: Mohan Bikram Singh, Chitra Bahadur KC, Narayanman Bijukchhe and Mahantha Thakur (who are thought of differently) have remained chiefs of their respective parties for decades.

The Maoist party that waged a war purportedly to shake age-old bad practices of Nepali society to uproot corruption, help lift the oppressed communities to power and establish a system based on equality was ruled by Pushpa Kamal Dahal for over 30 years. The party was merged with UML without ever handing over the leadership to new faces. None of the leaders of the political parties formed in Tarai-Madhes post 2005 have handed over party leadership. Six of these parties merged into one (RJPN), but leaders from all sides are co-chairs. Lust for power knows no limit here.

Such stagnation in the leadership creates serious void. First, it stops the rise of new leaders and discourages bright youths to join politics. Second, there is no entry of new minds and fresh ideas in the decision-making body. Same old ideas remain there and central meetings sound like eco-chamber of same opinions. While political leadership should be like a flow of river for fresh ideas, leadership in Nepal has become like old ponds.

Time to retire

Experience of leaders like Deuba, Nepal, Oli, Dahal and Bhattarai is certainly important. But do they necessarily have to cling on to official post like prime minister or president to use their knowledge and expertise? Can’t they contribute to politics and society even without becoming the party chiefs or ministers or prime ministers? They can but they do not.

Girija Prasad Koirala, Manmohan Adhikari, Sushil Koirala and Surya Bahadur Thapa were active in politics and were in power until they breathed last. Other leaders are there to continue that legacy. Even a leader with sound academic background like Baburam Bhattarai doesn’t see future beyond politics. Once a powerful Maoist Prime Minister, Bhattarai’s party is limited to a single seat in the Federal Parliament but he has failed to go beyond the same old methods of polity.

Of late, Deuba, Dahal and Nepal, all in their late 60s, have concentrated their strength on how to become head of the government or party for one more time. Khanal publicly expressed his resentment for not making him president earlier this year. Gautam and Paudel are desperate to become head of either government or the party at least once in their lifetime.

Why can’t leaders like Nepal, Paudel, Bhattarai or Subas Nembang establish a foundation, spread message of Nepal’s successful peace process, explain Nepal’s constitution making experience, work on Nepal’s nature and culture, or promote Nepal’s ethnic religious diversity to the international world?

They don’t need to cling on to power forever. Dear old leaders, you have worked a lot. Let new leaders emerge.

Twitter: thiralalbhusal

You May Like This

Failing leader

The poster boy of national progress and prosperity is losing his sheen, with his freshly-hung pictures looking down mockingly ... Read More...

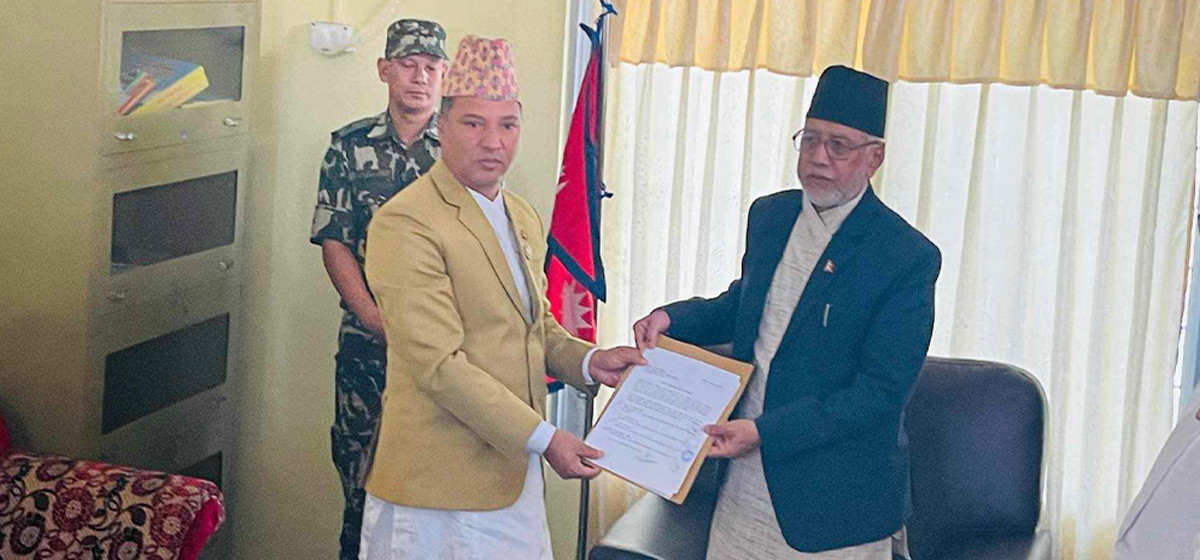

PM holds talks with RJP Nepal leaders

KATHMANDU, May 15: A discussion has been held between Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Rastriya Janata Party Nepal leaders... Read More...

It is not easy to federate a country as old as Nepal

Senior Nepali Congress leader and former finance minister Ram Sharan Mahat is an advocate of fiscally strong federal units. He... Read More...

Just In

- NEPSE nosedives 19.56 points; daily turnover falls to Rs 2.09 billion

- Manakamana Cable Car service to remain closed tomorrow

- Nepal govt’s failure to repatriate Nepalis results in their re-recruitment in Russian army

- Sudurpaschim: Unified Socialist leader Sodari stakes claim to CM post

- ED attaches Raj Kundra’s properties worth Rs 97.79 crore in Bitcoin investment fraud case

- Newly-appointed Auditor General Raya takes oath

- CM Mahara expands Cabinet in Lumbini Province

- FinMin Pun addresses V-20 meeting: ‘Nepal plays a minimal role in climate change, so it should get compensation’

Leave A Comment