OR

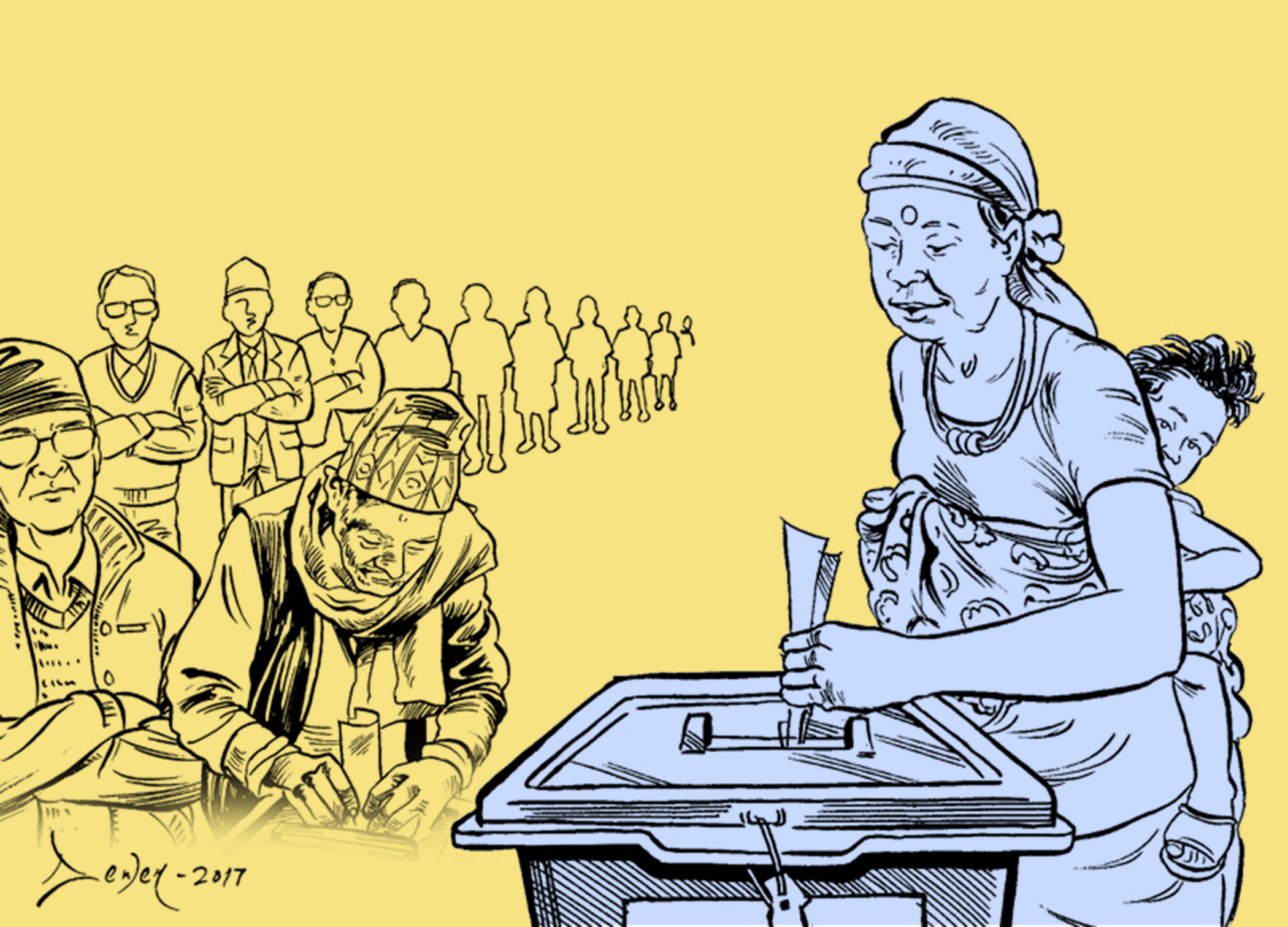

In a country that has relied on production and export of unskilled manpower for its sustenance, mimic man is an ideal. Naipaul is believed without being read in Nepal

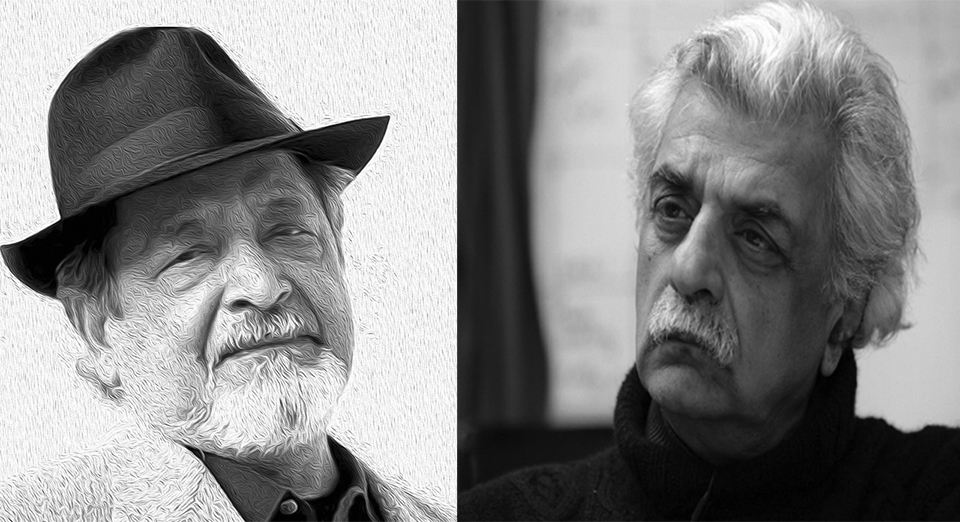

In a eulogy that simultaneously mocks and venerates Sir Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul (1932-2018), Tariq Ali writes in the London Review of Books blog, “Long before the knighthood and the Nobel Prize, it was the mirror that excited him. Destiny stared him in the face every morning. He believed in himself. The Trinidadian was to become a very fine writer of English prose.”

Perhaps there is some truth in the widely-held belief that what we say about others says as much about us as the subject of examination. Though a decade younger, Ali shares a life trajectory similar to that of Naipaul. Born to journalist’s households and relatively better-known maternal families, they went to Oxford, established themselves in competitive environment of England and turned out to be young achievers in the uncertain profession of letters.

Naipaul and Ali are what much later another nowhere person Sharmila Sen, who went up to Harvard and Yale rather than Oxford, would call “not quite white, not quite black, not quite Asian”. Both were brought up in traditional families but chose to be agnostics if not outright atheists. Comparisons need not be limited to similarities. Differences between the two are equally profound.

The Trinidadian, as the Pakistani chooses to call his senior, remained a writer throughout his life and was bestowed with Nobel Prize for his contributions to the English literature. The Pakistani, also ‘a very fine writer of English prose’, transformed himself into a global public intellectual of the Left.

Being a noteworthy prize, Nobel offers a considerable purse and a significant validation in the marketplace. But it can’t confer nobility upon its recipients. Naipaul was illiberal by conviction. Ali has been a Leftist by choice and is more than a celebrity in certain circles. For critics of neoliberalism, he belongs to the intellectual aristocracy of the people.

Leftists are not too well-known to be charitable towards their ideological opponents. If Ali took the trouble to asses Naipaul, predictably unfavorably with some back-handed complements thrown in for effect, perhaps it’s time to take a second look at motivations that make ambitious youngsters from ‘half-made societies’—a Naipaulian injunction—flee their homelands never to return.

It’s not just writers, people even in more focused professions such as anthropology, biology, civics, engineering, medicine and law draw nourishment from their roots to thrive in what can be called—in contrast to the Naipaulian characterization of the Third World—as ‘fully-evolved societies’. The ‘new’ in every field of endeavor can only be discovered, mapped, explained or improved upon from what exists in newer territories of exploration—the Terrai Incognitai that exists far away from metropoles.

Despite living in England for almost his entire adult life, Naipaul refrained from writing about what was ‘home’ to him. The Trinidad-born British writer of Indian descent kept mining minutiae of his memories and embellish them with impressions gathered during leisurely visits to the land of ‘others’ instead. Ali’s oeuvre is only slightly different; he pontificates about his ideological convictions in no uncertain manner, but his best works relate to the trials and tribulations of Pakistan, the country that he left behind to become a star of the leftist intellectual firmament.

Opinions about as great a body of work as Naipaul’s are bound to be divided, but it’s possible to argue that everything written after A House for Mr. Biswas is suffused with self-justification. The enigma of an émigré is that he can never leave home no matter how hard he tries to escape its mental borders. The everywhere person, irrespective of their achievements, are in fact nowhere people; their home lies in their memories. That’s a not such a nice place to be unless one chooses to be almost loveless, faithless, friendless and childless among many other things that signifies the normality of everyday life.

Unbounded individualism

There is an old saw in knowledge management which holds that whatever you can’t measure doesn’t exist. Perhaps a corollary is equally important in humanities—if you can’t theorize what you measure and analyze, then it remains a mere observation. Some of the French sociologists have been great theorizers. While Émile Durkheim (1858-1917) argued about collective consciousness, Jean-Gabriel Tarde (1843-1904) propounded that society was merely an aggregate of individuals. In Tarde’s view, individuals innovate, imitate or oppose which then makes societies progress or regress.

Innovation is a complex process that requires supportive environment. Education is important, but what actually spurs innovation is an ability to take risks and the capacity to handle pain and disappointments of inevitable failures on the way. The subaltern lacks the wherewithal to support risk-taking. Collectives look for security and conformism. Adventurism can also come from desperation of the ambitious. Both reasons can force innovators towards metropoles where there is enough friction to generate energy but not so much that it would kill a pioneer.

Opposition entails even higher stakes. While it’s true that only dead fishes flow with the current and swimming against the tide is the surest sign of life, human existence is slightly different from aquatic realities. Everything from standing up and walking is a constant struggle against forces of gravity. Oppositional stand puts additional burden upon the shoulders of survivors. Opponents do make breakthroughs for enhancement of human condition, but such a group is a tiny minority in any society.

That leaves the option of imitation for a large majority. Tarde says that imitation occurs through three laws—close contact, replication and insertion. All three takes place simultaneously when ‘the mimic men’ decide to transplant themselves among the ones that they consider to be their physical, mental and moral peers and superiors.

When the news of Naipaul’s passing away—it was reported that Crossing the Bar of the Victorian poet Lord Alfred Tennyson was read out to him when the call came—somehow a picture of Sir Vidia in his flannels and tweeds fidgeting with a Japanese toilet seat that has arrangement to wash the derrière with hot or cold water and then dry it with warm or normal gush of scented air at the flick of a button came to one’s mind.

Would Naipaul have preferred perfumed toilet papers that the high-end Japanese lodging houses stock their restrooms with instead? Perhaps the way one defecates or performs ablutions says more about the status of a person than what he eats, wears, and does and with whom he communicates or socializes. For sure, he wouldn’t have imagined going to the banks of Ganges—sacred thread deftly rolled around an ear to save it from contamination—with a pot full of water as generations of Naipauls before his grandfather must have done in the neighborhood of Kashi.

Great escape

It’s pure fantasy, but let’s imagine for a moment that a young Naipaul or an energetic Ali for that matter return back to their homelands after being ‘properly’ educated at colonial temples of learning. Perhaps Naipaul would still have written something like A Bend in the River while he worked at a travel agency in Trinidad or taught English to some well-endowed kids in an experimental school. Ali would have still written, lectured and raged against injustices of the neoliberal world from Lahore and then perhaps put behind bars or made a Prime Minister by the Deep State of Pakistan.

It’s extremely unlikely that Naipaul would have been read as widely or Ali would have been discussed as fervently had they decided to go back home. However, would their contributions to the betterment of human condition have been more remarkable? That’s a question nobody can answer with certainty. Imitation guarantees success while both innovation and opposition of Tarde’s formulation are so full of risks that few dare to challenge destiny head on.

In a paper that literary critic Homi K Bhabha wrote about mimicry in early-1980s, he quotes Sir Edward Gust from 1839, “To give to a colony the forms of independence is a mockery; she would not be a colony for a single hour if she could maintain an independent station.” Inability to maintain independent station continues to force multitudes to flee their homeland in hordes.

In a country that had continually relied on production and export of unskilled manpower for its sustenance since its creation—it’s impossible to imagine about Nepali culture, society and economy without the contributions of Lahures for over two centuries—the mimic man is an ideal. Little wonder, Naipaul is believed without being read in Nepal.

You May Like This

Priorities for power

Nepal can substitute almost 50 percent of imports of petroleum products and coal, if the government accords priority to... Read More...

Putin’s declining popularity

Putin’s image as a steward of Russia’s greatness and a symbol of hope is slipping away. His tried-and-true tactic is... Read More...

Standing up for the UN

To restore UN’s standing and influence to the level it attained under Annan will require stronger support from Europe, Canada... Read More...

Just In

- World Malaria Day: Foreign returnees more susceptible to the vector-borne disease

- MoEST seeks EC’s help in identifying teachers linked to political parties

- 70 community and national forests affected by fire in Parbat till Wednesday

- NEPSE loses 3.24 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.36 billion

- Pak Embassy awards scholarships to 180 Nepali students

- President Paudel approves mobilization of army personnel for by-elections security

- Bhajang and Ilam by-elections: 69 polling stations classified as ‘highly sensitive’

- Karnali CM Kandel secures vote of confidence

Leave A Comment