OR

Gaurav Bhattarai

The author is Assistant Professor at the Department of International Relations and Diplomacy, Tribhuvan University.news@myrepublica.com

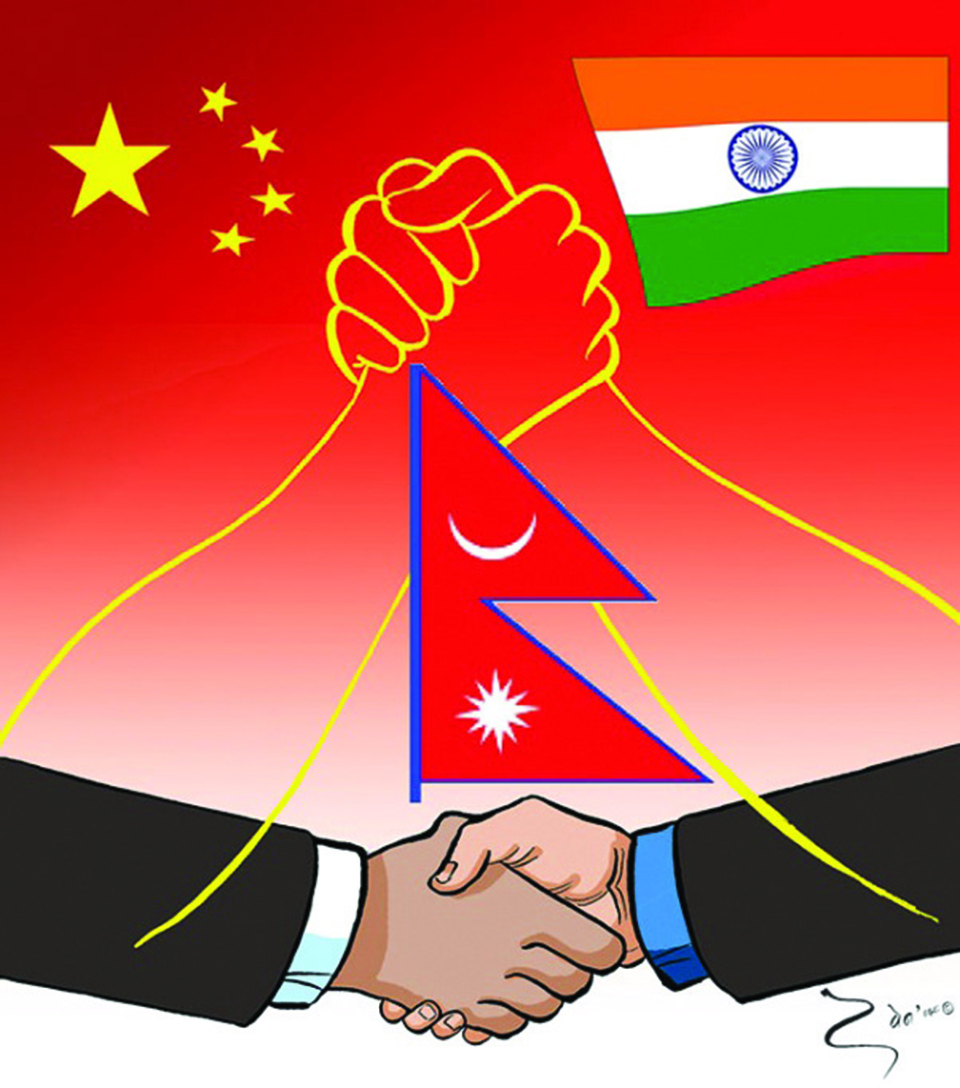

What are the new markers of Nepal’s neutrality when Nepali leaders are redefining Nepal as a bridge between India and China?

Since the fall of Rana rule in 1950 (subsequent to Indian independence of 1947 and after the communist takeover of China in 1949) Nepal has witnessed distinctively different political systems and different regimes. Interestingly, all kinds of political systems and regimes, hitherto, have preferred to lodge neutrality in their foreign policy making and foreign policy behavior, principally when it comes to Nepal’s neighborhood, or at times even beyond.

Neutrality has always received attention in Nepal’s foreign policy discourse. Some have lauded it for reaping geopolitical opportunities for Nepal. Others have aligned it to Nepal’s submission to the immense immediate neighborhood. Still, for Nepal, neutrality is not merely about refraining from any dispute or war. Some leaders in Nepal have exercised policy of neutrality in a strategic way while others have applied it in a contextual manner.

The neutrality King Mahendra exercised in 1962, when India and China were in war, was strategic and tactical in comparison to policy of neutrality that Nepal displayed in 2017, when India and China had standoff over Doklam. In 1962, neutrality was the upshot of Non-Alignment Movement (NAM) that was institutionalized in 1961 as the response of developing countries against the bloc politics of cold war period.

In 2017, neutrality was contextual in the sense that China was vying for increased influence in South Asia and India was persistently defending status quo in the region which could potentially have destabilizing effects in the region.

Hiding or binding?

During the Doklam crisis, Nepal, as expected, stayed neutral. Nepal’s manifested neutrality can be scholastically interpreted from twofold principles of ‘hiding’ and ‘binding’. Hiding refers to strategy of concealment. In this, third-party state resolutely prefers not to indulge in ongoing conflict between belligerents. Rather it decides to hide or conceal in the fear that it might not be advantageous. Nepal, which is often identified as a small state, opted to hide, instead of displaying any tilt to one of the conflicting forces during Doklam standoff.

On the contrary, binding refers to the strategy of unveiling state’s belief and faith. At this point, third-party state purposefully prefers to abide by international law and the idea of global peace. To see Doklam standoff through the principle of binding, we can say that adherence to UN charter, world peace, and global security barred Nepal from getting hauled into the standoff. But the Nepali state has not been able to identify whether it practiced hiding or binding forms of neutrality. Was Nepal frightful to disclose its tilt and priorities, and thus eventually opted to hide? If not, international community should be informed through Nepal’s foreign relations that Nepal abided. Or else Nepal’s adherence to the nonviolent world order and its unflinching belief in the promotion of world peace won’t be recognized in front of the false assumption that small states like Nepal chiefly hide in international conflicts. But this is not always the case. Small states also abide by international law and UN charter. For instance, last December, Nepal not only criticized the US decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, but also voted alongside 127 other countries in favor of United Nations General Assembly resolution on US President Donald Trump’s decision to shift US Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem of Israel.

Let’s take an example of 1962, when Nepali Gurkha fighters serving in Indian army were fighting against China in the brief border war between them. How can Nepal justify its adherence to neutrality in that case? Probably, it is exceptionally beyond the aforementioned principles of hiding and binding. In such situations, what are the ways available for Nepal to inform the international community that its neutrality doesn’t resemble a small state’s syndrome?

Assessing neutrality

Nepal’s neutrality has been characterized with the metaphor of yam by Prithivi Narayan Shah in his Dibhya Upadesh. Nepal was also identified as a buffer state during the period of British colonialism. What makes a country a buffer state? Two conditions are fundamentally inescapable. First, buffer state is situated between the two archrival countries and it is relatively smaller in size and influence than rival countries flanking it.

Today, while claims are still made that Nepal is a buffer state, we need to meticulously assess whether India and China are truly our archrivals. China and India fought a war in 1962, but it was limited to few border areas. At the moment, Sino-India relationship is based on different layers of cooperation rather than conflict. Wuhan meet between Prime Minister Modi and President Xi, Modi’s address in Shangri-La dialogue, and their vitalizing presence in bygone Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) conference exemplify the same.

Today, Chinese academicians have started touting Nepal as a gateway for China to enter South Asia since China has no diplomatic relations with Bhutan. Paradoxically, though India still is reluctant to join China-led BRI, ‘pro-India’ government in Nepal signed BRI agreement in 2017.

In this context, what are the new markers of our neutrality when Nepal’s leaders, including former prime ministers, are redefining Nepal as a bridge between India and China? We must explore answer of this question before glorifying neutrality as an indispensable element of Nepal’s foreign policy objectives.

Needless to say, neutrality is a strategy for small states like Nepal to cope with anarchic international system. Nepal needs to send a clear message to the international community that our neutrality is not that of hiding but of binding. Nepal needs to assert that 2017 Doklam neutrality was based on Nepal’s adherence to world peace, international law and UN Charter and that Nepal was not hiding but she abided.

The author is a faculty at TU’s Masters in International Relations and Diplomacy (MIRD) program

gauravpraysforall@gmail.com

You May Like This

Ayushmann Khurrana Redefining heroism in Bollywood

MUMBAI, September 4: From sperm donation to erectile dysfunction, Ayushmann Khurrana has become the poster boy of the unconventional films. The... Read More...

Redefining Teej

My 65-year-old Fupu never married but she has fasted since her childhood. She didn’t do so to get a good... Read More...

Redefining performance appraisal

Many working professionals must have envied the recent 25% hike in salary of government staffs. However, it is the time... Read More...

Just In

- Global oil and gold prices surge as Israel retaliates against Iran

- Sajha Yatayat cancels CEO appointment process for lack of candidates

- Govt padlocks Nepal Scouts’ property illegally occupied by NC lawmaker Deepak Khadka

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

- Court extends detention of Dipesh Pun after his failure to submit bail amount

- G Motors unveils Skywell Premium Luxury EV SUV with 620 km range

- Speaker Ghimire administers oath of office and Secrecy to JSP lawmaker Khan

_20240419161455.jpg)

Leave A Comment