OR

Bamadev Paudel

The author, a graduate from the Wayne State University, US, is now the chairman of Canada-based KarmaQuest International, a research-focused international charitynews@myrepublica.com

Having rails is what we will have to strive for ultimately but at the moment it is important to make provisions to address the urgent needs of people

Out of my routine of surfing Nepali online news portals over the weekend, I woke to the news that Prime Minister KP Oli was reiterating his commitment of plying rails on Nepali soil and having ships with Nepali flag on the ocean surface within next two years. That’s good for the country because we will have the first-ever modern rail and ship with Nepali flag if and when this dream comes true.

As such, being able to dream is the right of everyone and it is also a precondition to turn great things into reality. As nicely as it has been portrayed about the notion of right to dream in a recent Bollywood blockbuster Secret Superstar in which a suppressed Muslim teenage girl in a conservative family takes the point of her right to dream and adventures into going public through creating Youtube videos hiding her face in a burka to become a famous singer later on despite her terrifying father’s looming vehement opposition to it. For the Prime Minister Oli there is no such threat and he can do anything he likes overtly—thanks to overwhelming majority support he has in the parliament. However, that doesn’t mean that no one has right to comment on Prime Minister Oli’s dream and suggest some other alternatives that deserve attention at present.

No doubt, having rails and having gas pipes in each home is where we will be striving for but even more important at the moment is making provisions to address the urgent needs of the population.

After all, presence of rail doesn’t make much sense to a farmer in Humla district where apples are rotten on farms due to lack of roads. Besides, having only a Nepali flag on a ship in Indian Ocean is not going to mitigate anguish of Sete Kaami in Taplejung where he ferries his son on foot in a doko to the district headquarters, only to get painkiller tablets.

So what should be on the priority list of the new government? It should be to create an industrial base for the country so that we can employ young population within the country rather than sending them to the Middle East or Malaysia. Equally important is to substitute growing imports with our local products to mitigate our currently skyrocketing trade deficit. How long will the country manage budget in a sustainable way only through import duties rather than revenue generated from within the country’s production base?

Potential and reality

The idea of economic development was popularised mostly during the 1950s and 1960s. It has come a long way since, with paradigm shifts from trickle down approach in beginning years to heightened focus on human capital formation such as investment in health and education. Such shift in development approaches has been documented recently by Harvard Economist Ricardo Hausmann and MIT economist Cesar Hidalgo in their book The Atlas of Economic Complexity.

The core idea behind economic complexity is that the level of existing knowledge set available in a country is what matters for future growth. Complex economies or advanced economies weave vast amount of knowledge together to build the products and generate high value products whereas underdeveloped economies weave small amount of knowledge and produce less valued products. For example, Nepal produces handicrafts which require less amount of knowledge whereas France produces Boeing airplane which requires a very complex network of knowledge to create the final product.

Empirical evidences from around the world suggest that a country cannot switch to high desires all at once. For instance, agricultural dependent economy such as Nepal cannot switch to advanced industrial country overnight. There has to be a gradual movement because limited amount of knowledge set is not enough to generate complex products. Developing countries have this problem because even though they have entrepreneurs other nodes on production process are lacking. Lack of electricity and corrupt government make the matters worse. This suggests that focus of Oli government should be on these areas rather than to have unsustainable nodes of rails and ships.

Let’s take the example of Rwanda which is all set to head on to the path of prosperity after a long and dreadful genocide. The research on economic complexity of this country revealed that Rwanda’s productive knowledge is mostly related to growing of agricultural goods and herding of animals. Rwanda is now switching gradually to the production of next stage products requiring a bit of higher knowledge skill set such as processed foods and beverages and simple agricultural machinery, which uses both the existing know-how along with the growing productive knowledge in those areas.

What Nepal should do

What should Nepal prioritise in its future development efforts then? We are also in the same boat as Rwanda and we should also need to strive for neighboring products. Looking at Nepal in a product space map in the same study, Nepal’s high potential for the future based on what we are currently producing would include the adjacent possibles such as high quality products relating to garment and footwear. The map also shows that the country has potential for producing machines for preparing textile fibres and products based on minerals such as nickel bars and wires, but they appear to be a bit far to reach in product map based on the current knowledge set.

Similar to the model of Hausmann and Hidalgo’s economic complexity is the one advocated by Lewis-Fey-Ranis (LFR) model of economic growth which characterized much of the rapid development in East Asian countries. These countries moved gradually from agriculture-dominant economies to industrial economies by connecting their conventional agriculture sector to the industrial one gradually through both backward and forward linkages. South Korea, for example, now ranks fourth in economic complexity because this country accumulated a huge amount of knowledge skill set during the transition from agriculture to industry in the past half a century. Now it is dominant in the world economic landscape with the production of high quality goods—thanks to its skilled workforce.

We spent many years talking about development. Now is the time to delve into reality and achieve gradual and sustained progress, rather than going behind the whim of rail and ship with a Nepali flag. Building one railroad is not a big deal for a country’s prime minister as such but the greatness comes when a foundation is laid out so that the country heads to the path of prosperity in a sustainable way. Dreaming is easy but such dreams die as easily when true progress cannot be achieved.

The author is chairman of KarmaQuest International, a research-focused

international charity based in Canada

bdpaudel@yahoo.com

You May Like This

PM Oli applies brake on his railway dream

KATHMANDU, June 24: Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli said that it would take time for the much hyped railway to... Read More...

Nepal’s smart city dream

A number of mayoral candidates promised creating ‘smart city’ for rapid improvement in every aspect of city life. Will they... Read More...

Afghanistan kills Nepal’s world cup dream

KATHMANDU, July 25: Nepal’s dream of qualifying for the ICC U-19 World Cup has been shattered after facing 96 runs defeat... Read More...

Just In

- 70 community and national forests affected by fire in Parbat till Wednesday

- NEPSE loses 3.24 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.36 billion

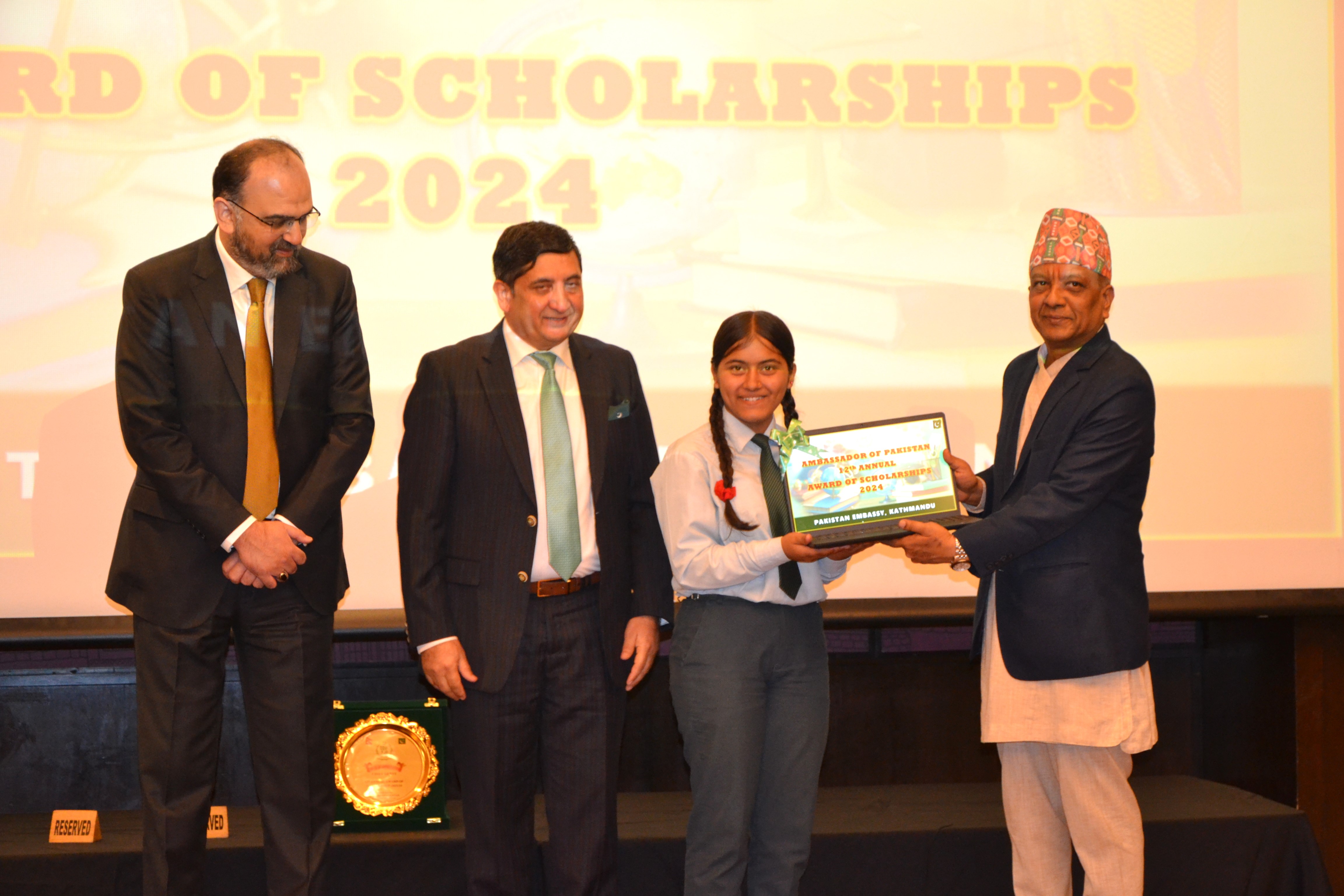

- Pak Embassy awards scholarships to 180 Nepali students

- President Paudel approves mobilization of army personnel for by-elections security

- Bhajang and Ilam by-elections: 69 polling stations classified as ‘highly sensitive’

- Karnali CM Kandel secures vote of confidence

- National Youth Scientists Conference to be organized in Surkhet

- Rautahat traders call for extended night market hours amid summer heat

Leave A Comment