OR

Compared to gargantuan sums involved in money laundering and illicit flows, domestic corruption deals with petty amounts.

On October 22, a weekly vernacular news magazine carried a detail story on possible money laundering by a reputed Nepali businessman. The story speaks of the businessman channeling Rs 11 billion worth of foreign loans into Nepal from companies established in tax havens like the British Virgin Islands and Cyprus. Out of this amount, the said businessman has already gotten Rs 8 billion and is waiting for the central bank’s approval to bring in the remaining Rs 3 billion. The news report also speaks of the businessman being under the scanner of the Department of Anti-Money Laundering Investigation (DAMLI) for amassing properties worth Rs 20 billion.

There are two aspects to this money laundering business: inflows and outflows of illicit earnings. The above story speaks only of flow of money into Nepal; it is silent on the possible outflows from Nepal. Inflow of foreign capital per se is not bad, as we are starving for FDI. However, keeping aside the cost of repatriation of loan and interest payments, the import of forex sans disclosure of the source raises many questions, particularly on the nefarious business of money laundering, that is, conversion of black money into white money.

Earlier, in April 2010, a study report on Sudan Scandal—on embezzlement of funds meant for procurement of logistics for Nepali peacekeepers in Sudan—submitted by the parliament’s State Affairs Committee had pointed out the need to investigate a deposit worth US $1 million (dated July 27, 2008) in the name of an unknown Chinese national by the name of WU Lixiang in the Nepal Bangladesh Bank, Bhaisepati Branch. The money was rumored to have come from commissions and kickbacks from the scandal.

Perfect hub

Nepal has traditionally been the perfect hub for money laundering. The unregulated border to the south, a large shadow economy, thriving trades in narcotic drugs and arms, human trafficking (including involving overseas employment and hundi remittances), the blossoming casino business, smuggling of gold and counterfeit currencies, organized crime and rampant corruption—all provide fertile grounds for money laundering and illicit financing in Nepal.

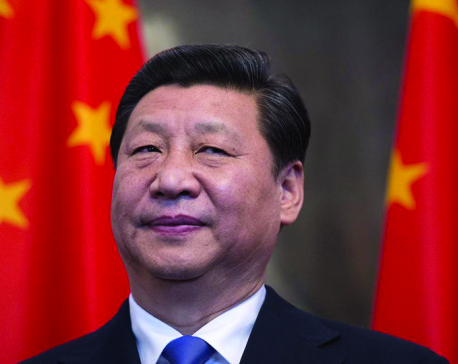

It is said that, with the intensification of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive in China (he is reported to have disciplined 1.34 million cadres already) smuggling of gold and foreign currencies related to Chinese citizens has gone up tremendously in Nepal. The highly regulated closed border to the north has become as much problematic as the open, free and unregulated border to the south. Imagine the situation if we had as open and free borders on the north as we do on the south!

On June 21, 2014, an English broadsheet reported on an abrupt increase in Nepali money deposited in Swiss banks between 2002 and 2013; and the deposits increased sharply after political changes in 2006. The money deposited in Swiss banks increased from a low of 24.76 million francs in 2005 to as high as 125.96 million francs in 2012. The names of these depositors will probably be never known, as perhaps will also happen with the names of dozen of Nepali citizens pointed out in the Panama Papers.

Nepal’s image on anti-money laundering is bad. In the latest anti-money laundering (AML) index published by Basel Institute of Governance, Switzerland, with a score of 7.57 this year, Nepal is ranked 14th among the list of 146 countries surveyed. This makes Nepal a high-risk country (10=high risk and 0=low risk). The Basel AML index measures a country’s anti-money laundering and terrorist financing framework, corruption risk, transparency and accountability, financial standards, and political rights and rule of law.

Bad to worse

Another UNDP study on illicit financial flows in LDCs from 1990 to 2008 had also indicated flows worth $419 million to $480 million a year from Nepal. Moreover, among countries with large cumulative illicit financial flows, Nepal was ranked sixth among 48 LDCs. With a total of $35 billion, Bangladesh topped the list; with US $9.128 billion, Nepal was sixth. Things must have worsened since.

The latest data on illicit financial flows published by the Global Financial Integrity puts illicit flows from Nepal for a decade (2005-2014) to be in the range of 2-10 percent of outflows and 3-10 percent of inflows of the total trade, which in turn is estimated as US $52,596 million for the period. From this one can safely estimate the amount of illicit inflow and outflow of money.

This is happening even though we had the Anti-Money Laundering Act 2008 and the Anti-Money Laundering Regulations 2010, as well as a Financial Information Unit (FIU) in the Central Bank and a five year strategy on Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism (2011-2016). There is little progress on controlling money laundering. The pressure for legal and institutional setups to tackle money laundering has come primarily from donors. Nepal’s compliance on the recommendations of the inter-governmental Financial Action Task Force (FATF) thus far has been minimal. Out of 49 recommendations, so far we have complied with only one recommendation, while we partially complied with 10, largely complied with three, while 33 were in the category of ‘waiting to be complied’.

The big fight

The global fight against corruption could be viewed through national and international lenses. At the national level, governments, anti-corruption agencies, civil society organizations, media and other stakeholders are waging a war on corruption. Since corruption takes place domestically, the role of domestic state and non-state actors in fighting corruption cannot be ignored. However, there are cross-border implications of corruption as well.

For this we need international cooperation. Therefore, there is a growing attempt to build knowledge related to anti-money laundering, recovery of stolen assets, strict detection and control of terrorist financing, extradition of corrupt leaders and elimination of safe havens that the corrupt people can use to hide themselves and their ill-gotten wealth. The idea here is to block cross-border transfer of corruption proceeds.

If we are serious about fighting grand corruption or catching big fishes, this is the area where we need to concentrate. Significant gains can be made by controlling cross-border money laundering. This must be the reason for significant reductions in illicit financing (SDG#16.4) and corruption (SDG#16.5) are among the new Sustainable Development Goals.

I do not for a moment suggest controlling domestic corruption is not important. But compared to the gargantuan sums involved in money laundering and illicit flows, domestic corruption deals with petty amounts. The reason we have failed to fight grand corruption is that we lack knowledge, experience, information and, of course, courage to fight money laundering and illicit financing.

The author is a freelance management consultant

You May Like This

Missing the forest for Xi

China has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty without adhering to Western approach ... Read More...

Ranibari forest, the single community forest inside ring-road

KATHMANDU, Jan 28: Ranibari Community Forest is being developed as a single community forest inside the ring road of the... Read More...

Missing the forest

Determination of boundaries of local units is not just about geography and population. It is the essence of political and... Read More...

Just In

- Govt receives 1,658 proposals for startup loans; Minimum of 50 points required for eligibility

- Unified Socialist leader Sodari appointed Sudurpaschim CM

- One Nepali dies in UAE flood

- Madhesh Province CM Yadav expands cabinet

- 12-hour OPD service at Damauli Hospital from Thursday

- Lawmaker Dr Sharma provides Rs 2 million to children's hospital

- BFIs' lending to private sector increases by only 4.3 percent to Rs 5.087 trillion in first eight months of current FY

- NEPSE nosedives 19.56 points; daily turnover falls to Rs 2.09 billion

Leave A Comment