OR

Due to the country’s overreliance on overseas employment and remittance, external labor relations will be policymakers’ priority in the future.

It is nearly 60 years since Nepal first drafted its labor law in 1958 called the Nepal Factory and Factory Workers’ Act (NFFWA). Prior to this, labor-related issues were dealt either through the civil code or applicable company law, including the laws of West Bengal. The spirit of the NFFWA was killed when the Panchayat regime in 1960 banned trade union activities along with political parties. For nearly 30 years, trade unions went underground and started working with banned political parties, resulting in politicization and fragmentation of trade unionism in Nepal.

With the reinstitution of multiparty regime in 1990, the NFFWA was replaced by a new labor law in 1992 and a separate law on trade unions in 1993. At the time of the enactment of the new law, the employers’ representative body, the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industries (FNCCI), was bogged down in infighting and hence overlooked the draft law. Since then they have relentlessly campaigned for labor law reform, accusing the law of being ‘pro-labor’ rather than ‘investment-friendly’. To add insult to the injury, the first amendment of the law was made in 1998 when Mukunda Neupane, the president of CPN-UML’s trade union, GEFONT, was the Minister of Labor.

Employers continued to push for reform demanding rights to hire and fire, ‘no-work no-pay’, rights to use contract labor, performance-based pay, and right to exit from business.

When an attempt to reform labor law through backdoor failed in 2001, employers signed an accord with three main trade unions on December 5, 2002. The unions then foiled an attempt to push a new labor law through ordinance during the king’s direct rule in 2005.

Now after more than 15 years of negotiations, on August 11, 2017, the parliament finally enacted a new labor law. Someone who has closely watched this exercise will conclude that the process has been as grueling as task of drafting the new constitution.

Incidentally, like the three-party national politics, there are also three parties to the labor dispute: the employers, the trade unions and the government. It will be too early to judge this new piece of labor legislation that is yet to be implemented. However, given the intensity of the debate on labor law reform, together with dramatic changes in Nepal’s labor market, it will be worthwhile to ponder possible gains and losses.

Flexibility v Security

The moot question is: Will this new law be able to resolve contentions between the capital (employers) and the labor (trade unions)? Any labor law must also correspond to the country’s political ideology and philosophy. But do we have such a policy and ideology?

Over the last two decades, the crux of the debate rested on two opposite premises: the employers demanding labor market flexibility and the trade unions demanding increased job security. The stand of the employers was that the law is too rigid, therefore nearly impossible to implement. The trade unions, on the other hand, argued that the employers’ demand for flexibility was a sham as they had never abided by the law’s provisions. Due to laxity on the part of the government, the law was never enforced, and the employers already enjoyed a kind of perverted flexibility, the argument went. This in turn made the unions demand “flexibility for labor” rather than “flexibility of labor”. The employers’ call for law reform is nothing more than a bargaining chip, said the employees, to settle other issues like amortization of loans and interest, tax rebate, market protection, tariff reduction and duty drawbacks.

The flexibility v security debate is in fact a global phenomena tied with the globalization wave of 1990s. In 2009, after reservations from the International Labor Organization (ILO), the World Bank dropped the measure of labor flexibility from its composite “doing business index (DBI)”. The implied meaning of the debate is that more flexibility means less security and vice versa. Denmark, on the other hand, had carefully developed a concept called “flexicurity” seeking to address the two contending issues simultaneously.

Instead of taking flexibility and security as two mutually exclusive, either-or concepts, the drafters of the present law have sought to address both together, giving (some) flexibility to the employers and (more) security to the employees. One significant gain for the employers is that they have been able to expel the dreaded clause in the erstwhile law whereby employers would have to give permanent status to their employees after 240 days of probation. Once made permanent, it would be nearly impossible to fire an employee.

Hire and fire

This is what the employers were demanding under the concept of “rights to hire and fire” and they now have a degree of hiring flexibility. They can hire workers under regular, contractual, piece meal, casual or daily wage basis or through labor contractors. They can even employ workers, albeit for a limited time, as trainees and apprentices. This is definitely a gain for the employers. However, this gain is constrained by a binding requirement to issue appointment letters specifying terms and conditions of employment. Given the distortions created in the labor market by having “permanent” and “temporary” workers, the new law is expected to do away with this duality.

One good thing about the law is that unlike the previous law that is applicable only to those businesses having more than 10 employees, the new law is universal, albeit with reservations for specific cases like collective bargaining and labor relations committees. Compared to previous law, the current law is broader and more encompassing. One can judge this from the size of the law itself. There are a total of 183 clauses spread over 24 chapters; in comparison, the previous law contained 92 clauses and 11 chapters.

The employers may have been able to delete the word “security” from its preamble but the law contains enough security provisions for the workers. Revision of minimum wages after two years is now mandatory. The management cannot lay off workers without consulting trade unions. If the counterpart trade union act restricts the management from transfer and promotion of union officials, the present law goes one step further to restrict lay off of union officials. There are full chapters seeking to regulate: a) working hours and overtime, b) payment of remuneration, c) leaves and holidays, and d) provident fund, gratuity payment and insurance. Gender issues like sexual harassment, maternity leave and occupation health have also been addressed.

On a positive note, the “cooling period” has been considerably extended to avoid wildcat strikes. The new law makes mandatory provisions for compulsory arbitration of labor disputes before entering into strikes and lockouts. The employers’ demand for “no work, no pay” has now been addressed by the new legal provision to pay only 50 percent of remuneration during the period of legitimate strike and lockouts. The law has also specified that no legal charges can be filed against economic losses and damages during strikes and lockouts, however, compensations can be extracted, as per law, from the concerned individual or the group for deliberate physical damage and losses due to arson and destruction. There are also provisions for collective bargaining at sectoral level.

Besides, under the new law, a new tripartite institution has been proposed to deal with labor related policy issues: a 13-member Central Labor Advisory Council representing the government, the employers and the trade unions. Many labor issues in the future will be decided by this apex body.

The big picture

Will this new law address the contentious issues of labor relations in Nepal? What could be its possible impacts? With increased overseas employment, there is now a labor crunch in Nepal. The employers have started feeling it too. As a blessing in disguise, labor shortages have helped increase general wage rate. This must be why the employers have agreed to the new law when they knew that unions had an upper hand in it. One must not be misled by media reporting of serpentine queues of applicants whenever there is a vacancy.

This is more a sign of growing ranks of educated unemployed than general unemployment per se. In the days ahead, due to (over)reliance on overseas employment and remittance, the issue of external labor relations will be an overriding concern for policymakers. The government will have to be more occupied by labor strikes by Nepali laborers in Malaysia, South Korea and Gulf countries than by labor strikes in Nepal. The new labor law addresses only internal labor relations, and as these internal labor relations get less priority, this could explain the laxity in its drafting.

At a time when the ILO is itself mulling the future of work—from its earlier decent work program—the drafters of new law have failed to understand the shape of the work in future. They have been too occupied with flexibility and security. Likewise, trade unions have been myopic in advancing social security when the concept has failed even in many advanced countries. How will the country cope with social security of the millions of Nepali workers who are expected to return home from their overseas employment? As such, the growing size and scale of overseas employment business is expected to overshadow the new labor law.

You May Like This

Harmonizing of rules discourages informal trade between Nepal and India

BIRGUNJ, Sept 11: India implements international goods and services tax,while Nepali traders should have EXIM Codes to trade ... Read More...

Rules for writing

There are no rules for good writing, except the rule of understanding context, complexity, and change ... Read More...

Kate Upton announces engagement to Justin Verlander

NEW YORK, May 3: Kate Upton has announced her engagement to baseball star Justin Verlander. She tells E! News that... Read More...

Just In

- Fire destroys wheat crop in Kanchanpur, Kailali

- Bipin Joshi's family meets PM Dahal

- State Affairs and Good Governance Committee meeting today

- Gold items weighing over 1 kg found in Air India aircraft at TIA

- ACC Premier Cup semi-final: Nepal vs UAE

- Sindhupalchowk bus accident update: The dead identified, injured undergoing treatment

- Construction of bailey bridge over Bheri river along Bheri corridor reaches final stage

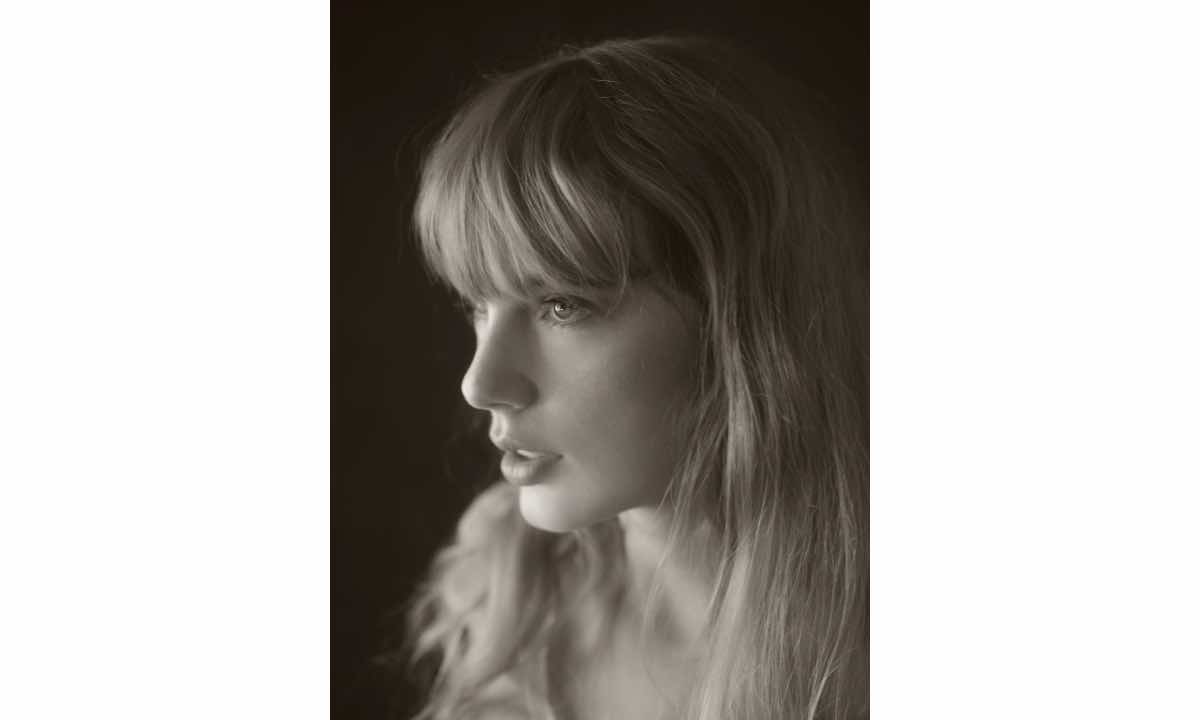

- Taylor Swift releases ‘The Tortured Poets Department’

Leave A Comment