OR

A few weeks ago at Devnagar, Nagarjun municipality, there was a community meeting over a hot-button issue. Can you guess what the issue was? Water.

The meeting came amid complaints from people living farther from the local water source located on the foothills of a nearby forest. The people living farther off were apparently reeling under an acute water shortage. Some participants, quoting those living farther who were absent, said the absentees wanted to lay a pipeline from the end point of the existing pipeline. However, those living comparatively closer to the source turned down this request, pointing that installation of another pipeline from the end point will drain their source of water and leave them high and dry. The meeting concluded that ‘the affected party’ should install a pipeline at the source itself.

This meeting can be an eye-opener for all, including our government, provided they are not pretending to be fast asleep. The event makes it loud and clear that conflict over water will escalate amid increasing scarcity.

Whether it’s over the Nile, the Mekong or our very own Koshi, Gandaki, Karnali or Mahakali river systems, humanity is witnessing increasing conflicts over water—for irrigation, fisheries, drinking and navigation. But we, sitting on the lap of the Himalayas, a major source of river systems that are a lifeline for South and Southeast Asia, seem concerned only about generating and exporting hydropower, and making a small fortune, oblivious to the fact that while humanity has other sources that can generate energy, only a handful of sources can supply usable water.

Major cities in developing countries have been facing water crisis for years and Kathmandu is no exception. A proverbial Kakakul, the Kathmandu Valley has been waiting desperately for years to quench its thirst with water from the Melamchi River. The situation is trickier still in other parts of the country that are considered rich in water resources, with people, including children of school-going age, having to trek for hours to fetch a pale of water.

Melamchi muddle

Back to the Melamchi. The 2015 Gorkha Earthquakes and the subsequent Indian blockade are two major factors that have delayed the ambitious project that aims to bring 170 million liters of water a day to Kathmandu Valley in the first phase. In the second phase, the project aims to channel waters from Yangri and Larke Rivers into the Melamchi, bringing a further 340 MLD to the valley and its outskirts.

While wastewater and pipe laying works are underway in Kathmandu, there are a number of challenges that the project will have to face before it can bring fresh, safe Melamchi water to valley denizens. Absence of rocky surface along a stretch of the under-construction tunnel means more digging, which takes more time. That’s not the end of trouble, though.

According to reports, while 30 landowners have accepted government compensation for land acquired for the Melamchi subproject-02 in Katunje, Bhaktapur, 26 landowners have been demanding current land prices. This indicates that compensation for land acquired for the project may turn out to be a major issue in coming days. Local political leadership can play a vital role in resolving such disputes and ensuring early project completion.

As new federal, provincial and local administrative hubs are developed, more and more water will be needed.

The Devnagar episode is also reflective of disputes over water sovereignty all over the world, disputes that have taken a huge toll on smaller and weaker countries. Thanks to years of political instability and poor institutional capacity, Nepal has been seeing progressive weakening of its water sovereignty, thanks to the Koshi Agreement, Gandak Agreement, the Mahakali Treaty/Agreement and unilateral construction of illegal structures along no-man’s land down south. As the country moves ahead on the path of federalism, federal units are likely to engage in more disputes over water resources.

Nepal first

As they go about developing new federal, provincial and local administrative hubs, human density in these hubs will increase, and they will need more and more water.

As Nepal goes fully federal, development partners like the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank should not shy away from investing in mega projects citing lack of institutional capacity. A case in point is the ambitious Arun III project that became the victim of Nepal’s perceived/real lack of institutional capacity, environmental activism and extraterritorial interests, consigning Nepal to hours and hours of power outage and taking a huge toll on its industrialization. Now there are talks of developing it into an export-oriented project, by and large at the cost of Nepal’s water sovereignty.

Amid increasing disputes over water, development partners should help build institutional capacity of smaller, weaker countries instead of staying aloof, which is tantamount to selling these countries down the river. They should help countries like Nepal strengthen their water sovereignty by providing technical knowhow and expertise. If they want to create a just and peaceful world, they should invest more in water, irrigation and hydropower projects that meet these countries’ domestic requirements first, for in most cases, bigger, mightier countries have been enjoying a monopoly over the use of these vital resources.

Damming rivers on foothills and developing multipurpose projects that meet energy, water and irrigation requirements of mega cities, and providing water to millions of people across national borders may be feasible for some, but it does not stand on a solid footing in a country known for water scarcity and high seismic activity. So the focus should be on building water supply, irrigation and hydropower infrastructure by taking into account the carrying capacity of the terrain and putting domestic need at the forefront.

Multilateral agencies shall help smaller countries like Nepal develop such environment-friendly infra by providing concessional loans and technical assistance. Is that asking for too much?

You May Like This

Why Federalism has Become Risky for Nepalese Democracy

The question arises, do federal or unitary systems promote better social, political and economic outcomes? Within three broad policy areas—political... Read More...

Nepal's Forests in Flames: Echoes of Urgency and Hopeful Solutions

With the onset of the dry season, Nepal's forests undergo a transition from carbon sinks to carbon sources, emitting significant... Read More...

'Victim blaming'- Nepali society's response to sexual violence

Multiple studies show that in most sexual assaults, the attacker is someone known and trusted by the victim. ... Read More...

Just In

- Govt padlocks Nepal Scouts’ property illegally occupied by NC lawmaker Deepak Khadka

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

- Court extends detention of Dipesh Pun after his failure to submit bail amount

- G Motors unveils Skywell Premium Luxury EV SUV with 620 km range

- Speaker Ghimire administers oath of office and Secrecy to JSP lawmaker Khan

- In Pictures: Families of Nepalis in Russian Army begin hunger strike

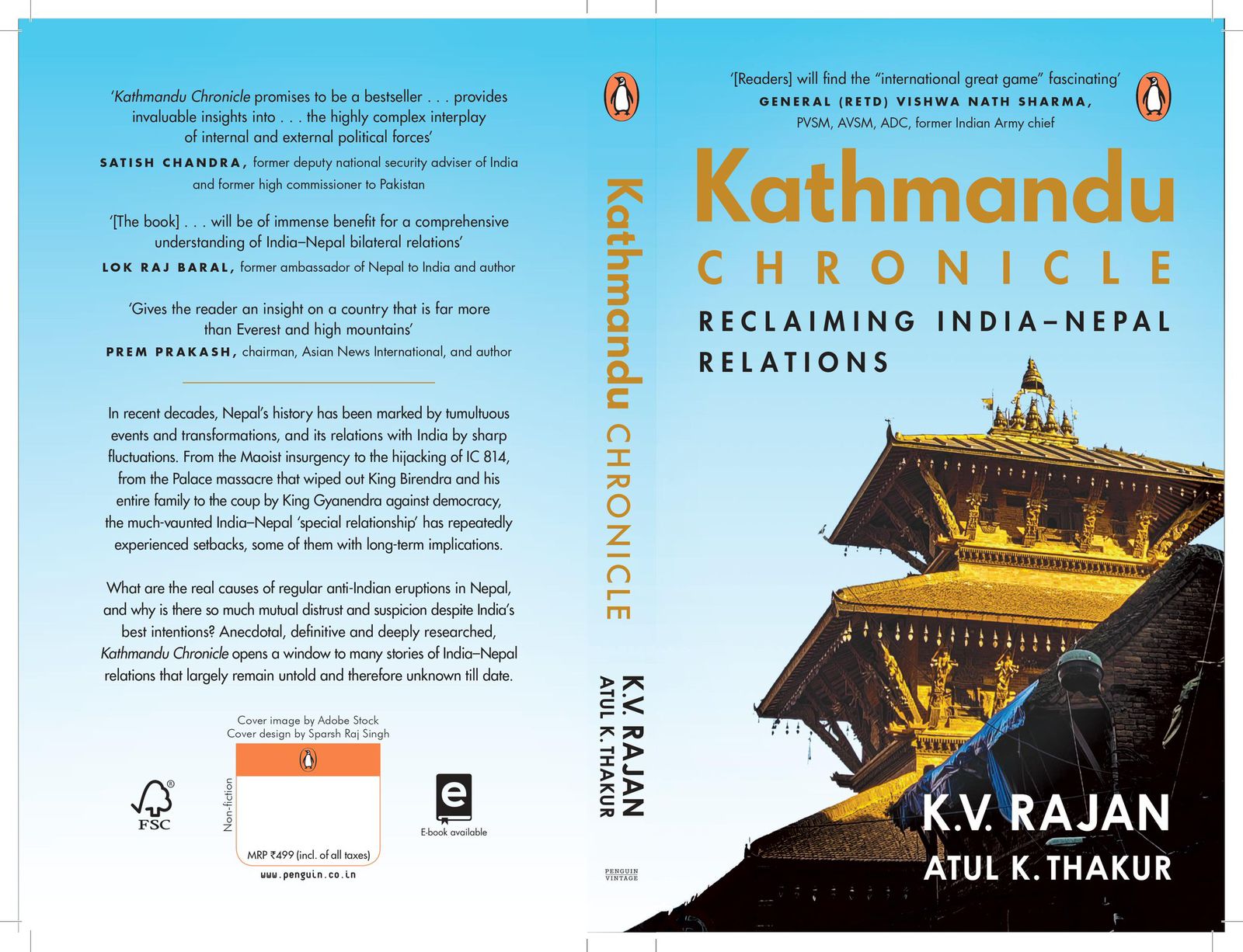

- New book by Ambassador K V Rajan and Atul K Thakur explores complexities of India-Nepal relations

_20240419161455.jpg)

Leave A Comment