OR

Shuvechha Ghimire

The author is a Sociologist from Jawaharlal Nehru University and ‘Wine Feminists’ is a term she coined. Also, the opinion expressed is personal.shu.ghimire@gmail.com

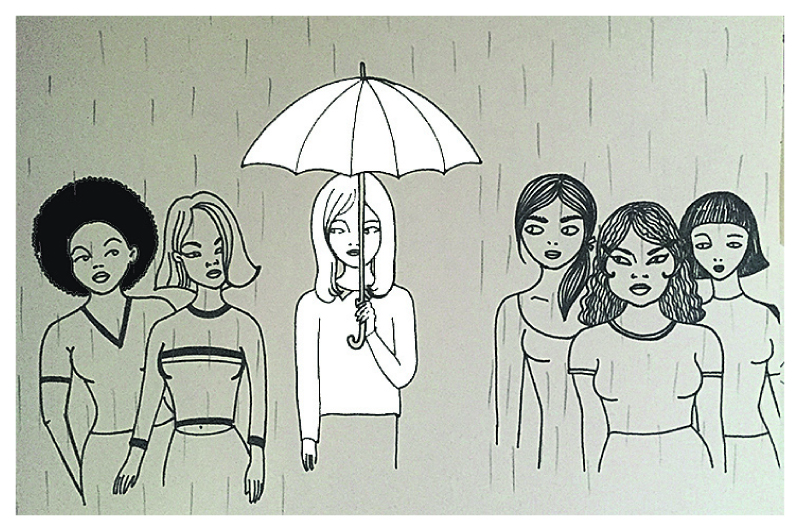

There is a term often used in army circles and strategic studies: “Whisky Generals”. A term used to define high-ranking army commanders who sit in their offices and clubs sipping whisky and smoking cigars, completely detached and unaware of the situation on the ground. In the context of women’s rights movement, especially in Nepal, there has been a steady rise of a group of women who can best be termed “Wine Feminists”.

These are those self-styled feminists who are often found in conferences and parties in Kathmandu, sipping their wine and talking about women’s rights. Like the “Whisky Generals”, the “Wine Feminists” of Nepal living in their comfortable houses in rich suburbs of the city are also blissfully detached from ground realities. They, of course, occasionally visit the field for a surficial observation and to justify their massive international funding, after which they sit comfortably in TV studios and conferences where they discuss their findings, while waiting for lunches and more wine. They are a curious combination of being highly educated and liberal in their expressed views in public yet shockingly conservative in their private lives.

Namrata Sharma is one such self-styled feminist, a “Wine Feminist” in its classical sense. Her interview with Sagarmatha TV on Woman’s Day (now available on Youtube) was a revelation of the obvious. She glorifies her role as a woman, which is limited to being a daughter, sister, wife and a mother. This is a reiteration of patriarchal values that she should ideally be opposing. These values take away the agency from a woman and typecast her in certain societal roles, refusing to see her as a distinct individual, a fact that should be obvious to every genuine feminist.

The interview, apart from eulogizing her modest achievements to epic levels, was also a demonstration of everything that is wrong with such “Wine Feminists”. She seems to believe that Nepal has made enormous strides in the past few decades, which may be true for certain areas but for many women all over the country this is unfortunately not accurate. Take the plight of women during menstruation in certain parts of western Nepal (Daneille Preiss, 2016), which is a result of anarchaic tradition made into a law in the mid-19th century (Andras Hofer, 1979). Further, she seems oblivious to the variations in the traditional laws and customs of various caste and ethnic communities, such as those of the Limbu, Rai, Magar, Gurung, Tamang Sherpa, etc., (Rajesh Gautam/Asoke K. Magar, 1994) where the role of woman in that particular society varies and as such requires different strategies and methods to deal with.

Sharma’s example of the obstacles faced by Dalit girls and their quest for higher education is again problematic. She presents the problem of higher education among girls as caste specific rather than a pan-regional one, as is the case. Her manner of presentation of the problem smacks of caste biasness. Finally she seems clueless that most oppressive laws and traditions in Nepali society, especially dealing with women and caste, can be traced back to the Brahminization of laws and customs, imposed by the Gorkha state in the 19thcentury, (M.C Regmi, 1971) of which her family (the Pandeys) were an important part.

Sharma’s opinions are also colored by the fact that she belongs to a certain section of Nepal’s society; the Kathmandu high class and high caste elite. Their opinions are shaped by the fact that they live in privileged and rich sections of the capital, belong to upper class of Nepal and are invariably from the so-called “upper” castes. The people of this section are those who live in their own country as foreigners and they are oblivious to the people living outside their city and their gated communities. They are those who believe that they have more in common with foreigners who come to visit exotic Nepal and in front of whom they claim to be the representatives of the country.

They visit places like Mustang on vacations but know nothing of its people and their social structures. For them, the beauty of the place is divorced from the people living there. For them the Waltz is much more familiar dance than is the Limbu Chyabrung; they proudly claim to know the Salsa but are oblivious to the Tamang Selo. They are those who club the people to whom the Limbu Chyabrung and Tamang Selo belong as “Janjatis”, “Bhotes” and “Madhesiyas” without even attempting to know the differences or the names of the ethnic communities or their different cultures.

They are those who claim that caste is an alien concept, even laugh at the very suggestion of its existence but would never allow a Dalit to come anywhere near their kitchen or their places of worship. They claim to be modern but would never marry their children outside their caste. It is thus laughable that they claim to be the avant-garde of women’s movement of Nepal.

One needs to ask whether the women’s rights movement should be associated with people who claim to speak of women’s freedom but would never eat before serving food to their husbands or their sons, or those who expect their daughters and daughter-in-laws to be virgins before marriage, if not subtly ask them for a Hymenorrhaphy and to remove their tattoos and to behave in a certain way in public. Thus one can say that one of the most difficult challenges that women’s rights movement faces today is reclaiming the movement from such “Wine Feminists”. They are an obstacle to the goal of women equality that they claim to aspire for. One yearns for the day when people like Anuradha Koirala will claim the leadership and representation of women’s rights movement in Nepal.

The author is a Sociologist from Jawaharlal Nehru University and ‘Wine Feminists’ is a term she coined. Also, the opinion expressed is personal.

You May Like This

Five ways technology is changing the wine we drink

From drones to machine learning, new technologies are helping winemakers improve both the quantity and quality of their wine ... Read More...

Old wine, old bottle

Last week, a grand coalition of all the leftist parties of Nepal was announced, much to the surprise of not... Read More...

Wildfires kill at least 10 in California wine country

SANTA ROSA, Oct 10: Wildfires fanned by strong winds swept through northern California’s wine country on Monday, killing at least... Read More...

_20220508065243.jpg)

Just In

- MoHP cautions docs working in govt hospitals not to work in private ones

- Over 400,000 tourists visited Mustang by road last year

- 19 hydropower projects to be showcased at investment summit

- Global oil and gold prices surge as Israel retaliates against Iran

- Sajha Yatayat cancels CEO appointment process for lack of candidates

- Govt padlocks Nepal Scouts’ property illegally occupied by NC lawmaker Deepak Khadka

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

Leave A Comment