OR

Classes at the Kathmandu Bahira Sangh, Gairidhara, at any given time, are understandably eerily quiet. But on your visit, you shall find the students actively participating and their instructor, Gokul Risal, teaching rather enthusiastically.

Currently, they are learning to sign food items. Risal starts the session by writing down 50 food items on the blackboard and begins to sign them one by one. Dhan, bhatamas, beer, on it goes and his group of students, which comprises of both deaf/mute people as well as those without the impairment, follows him.

The silence is only interrupted by occasional giggles but before you know it, they seem to have managed an elaborate conversation. One can tell, because Risal begins writing down extra non food related words on the blackboard. Dharma, tree, vacation, in a couple of minutes they seem to have covered a lot of ground and their class quietly continues without losing any momentum.

In the nearly three decades of the Kathmandu Bahira Sangh’s existence, these sessions have been mainly off the outside world’s radar. But to the people present in the classroom, it continues to prove to be essential. At the 7:30 am class, Risal relies on his only two pupils who can hear and speak to help him put his point across. Two months into the class, it isn’t exactly easy for the students to interpret all his signs yet.

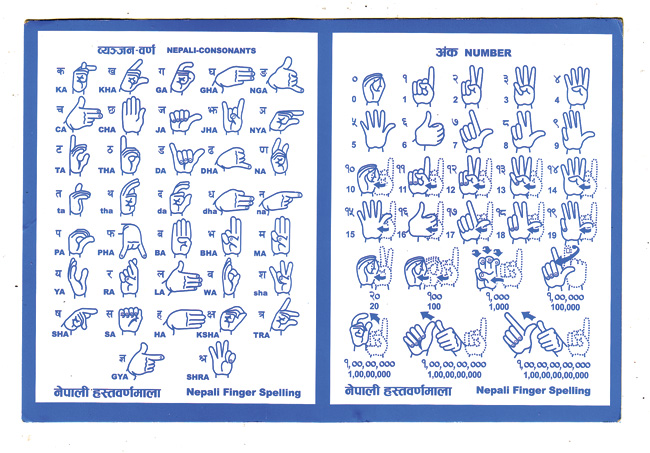

Each movement and position of each finger in their two hands plays a part in relaying their message and forming a conversation. Risal consciously makes it a point to sign slowly but Sarswati Binjankarau, one of the students without any impairment, cheekily points out that it’s still useful to know how to put two fingers together on the other palm and tap it two times, to ask the other person the meaning of what they just said.

As it is, Risal seems to be overflowing with information. He makes several slapping motions with his hands to explain the kind of rebuke they received whenever he and his peers tried to use sign language during his school days. This was back during the 1970s and the teachers in Nepal preferred oral methods to teach the students. Thus, the likes of Risal largely had to rely on their lip reading skills to understand.

Shilu Sharma, vocal translator at the Kathmandu Bhaira Sangh, helps set the scenario. She explains that it was only when foreign mute tourists visited Nepal and tried to get in touch with the local mute community that Nepali mute and deaf individuals discovered the method of using systematic sign language for communication. Prior to this, they simply resorted to random gestures and hand movements.

So one could say that the year 1981 proved to be a significant one for Nepal’s deaf and mute community. The date is even commemorated in posters that are hung at the Kathmandu Bhaira Sangh’s door. The posters have several pictures of the founding members taken back in the day and Risal proudly points at himself.

Now while they instantly realized the benefits of signing to communicate, in absence of native Nepali sign language, initially, the deaf and mute community here too started making do with sign language in English. Eventually, this turned out to be quite a trend. For the longest time, the mute and deaf community in our country didn’t have an official language. Risal even remembers those around Bhairawa signing in Hindi. It was clear that the majority from their community were siding with convenience. They were increasingly losing their motive and desire to create Nepali sign language and use it as well.

The founding members of the Sangh though felt otherwise. Risal shares that they even had to stage some protests within their own community to make their stance known. So despite the slight resistance, the 20-25 members of the Sangh got together and came up with around 500 Nepali word signs in a mere week’s time. Later, they also personally put in the effort to spread the instructions throughout the various regions of the country to make it official.

Thus, today all these years later, Risal relays his immense pride in conducting these classes at the Sangh. While the Sangh holds afternoon classes for the elderly who are only now learning how to communicate in proper language, his other classes host a variety of individuals.

If Sarswati Binjankarau, the student who was helping interpret Risal earlier, is attending because of her work experience taking projects to the rural areas and not being able to communicate with the deaf and mute community, Sushil Dhungana, a video editor, who is partially deaf but has fully deaf/mute parents, for instance, wanted to learn how to express himself better to his mother. So far, he had apparently only been using limited gestures to communicate with her.

Dorje Lama, on the other hand, recently rejoined the morning sessions at the Kathmandu Bahira Sangh. It’s been five years since he first learned to sign but since most of the deaf and mute in his Gorkha village don’t know sign language, he shares he barely gets to use it. He has been so out of practice that he admits he has forgotten a large chunk of all that he had learnt.

Risal points out that this is a common phenomenon. He is used to having students especially of 30 years and above retake his classes because they don’t have people in their circles to practice with. Even at the moment, there is only one guardian with a deaf and mute family member that he has been teaching. Her name is Sunita Sharma and she has been learning to sign for her maternal uncle.

She too has only been attending the classes for two months now but she says she has already discovered that her uncle has quite the sense of humor. She says, “This duration of the course is six months and it costs only Rs 3000. I think it is a cheap price to pay to get to see this side of the world.” These days, what once seemed like random hand gesture have turned into real conversations for her and she claims to love it.

priyankagurungg@gmail.com

You May Like This

City signs defender Danilo from Madrid after selling Kolarov

MANCHESTER, July 23: Danilo will be fulfilling his ambition to play under Pep Guardiola after signing for Manchester City from... Read More...

Nepal signs three-point agreement with India

New Delhi, India, Sept 16: The Government of India is to provide project management consultancy service for the road upgradation... Read More...

CBIL, BRCL signs remittance agreement

KATHMANDU, July 21: Citizens Bank International Ltd (CBIL) and Boom Remittance Company Ltd (BRCL) have signed an agreement to provide... Read More...

Just In

- 120 snow leopards found in Dolpa, survey result reveals

- India funds a school building construction in Darchula

- Exploring opportunities and Challenges of Increasing Online Transactions in Nepal

- Lack of investment-friendly laws raises concerns as Investment Summit approaches

- 550,000 people acquire work permits till April of current fiscal year

- Fixing a win by outlawing dissent damages democracy

- MoHP cautions docs working in govt hospitals not to work in private ones

- Over 400,000 tourists visited Mustang by road last year

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment