OR

We must aim for a socially inclusive country that ensures the welfare of a broad section instead of serving few elites

Some scholars argue that Nepal’s inclusion modality based on gender, caste, ethnicity and disability is not perfect and therefore the ‘class factor’ should rather be considered. If so, what about issues of class within class? Class is a political concept, as propounded in Karl Marx’s philosophy of class struggle. But can focus on class alone address multidimensional issue of exclusion?

The historical roots of social exclusion can be traced back to the times of Greek philosopher Aristotle. Contemporary notion of exclusion emerged in France in the 1970s, following the breakdown in social cohesion following the civil unrest in 1960s, in the broader context of growing unemployment and socio-economic inequalities. From France the concept spread through European Union. It was adopted particularly enthusiastically by UK’s New Labor government in the late 1990s, when the International Labor Organization also took a lead in pushing the concept in less economically developed countries.

Father of economics Adam Smith defined social exclusion two hundred years ago as the “inability to appear in public without shame”. This applies to marginalized Dalits in Nepal more than to other community groups. They are deprived of social interaction, such as appearing in public freely or taking part in social, cultural and religious functions.

When I raise social inclusion issues in relation to Dalits, most of my so-called upper caste colleagues respond: “Brahmins are as poor. So why should there be reservations only for Dalits?”

I am mindful that many upper-caste people are also poor. There are poor within Brahmin and Chhetri communities, even while some rich Brahmins and Chhetris monopolize state resources. But social inclusion is not only about being poor or rich. Poverty is but one of multidimensional facets of social inclusion.

But Brahmins and other so-called high caste groups were not systemically excluded from the society. Dalits were.

In Kathmandu Valley King Jasyasthitiraj Malla (1382-1395) introduced an elaborate system of 64 castes among Newars. In Gorkha, Ram Shah (1605-1633) adapted this model into a less structured form. The Muluki Ain (1854) was the strongest manifestation of exclusion of Dalits. It was discriminatory not only towards Dalits but also towards women, Janajati, and Christian and Muslim minorities. So in 1963 it was amended by repealing some penal clauses on untouchability.

The Constitution of Nepal (1990) guaranteed equal rights to all its citizens, saying that the “State shall not discriminate against citizens on the basis of religion, color, sex, caste, ethnicity or belief” (Article 11.3). But the 1992 amendment of Muluki Ain retain this discrimination by positing that “traditional practices at religious places shall not be considered as discriminatory”. That means the caste groups once labeled as ‘untouchable’ would still have no access to shrines and temples. This was a flagrant exclusion of Dalits from the social sphere.

The preamble of the new constitution (2015) envisions an egalitarian society “founded on the proportional inclusive and participatory principles in order to ensure economic equality, prosperity and social justice, by eliminating discrimination based on class, caste, region, language, religion and gender and all forms of caste based untouchability”.

Despite this, upper caste Hindu communities continue to keep Dalits away from temples.

Dalits have to struggle to get a house on rent in Kathmandu. They are not allowed to enter many hotels and restaurants. Dalit students are discriminated in school during functions like Saraswoti Puja. High caste people still hesitate to share food or eat together with low caste people. So caste discrimination and untouchability has remained a fact of everyday life in Nepal. This is the reason a number of Dalits have converted to Buddhism and Christianity.

Thus legislation or policies on inclusion and reservation alone cannot transform the society. A broad awareness and sensitivity campaign is required to break the evil practice of discrimination. Dalit issue is not only about reservations, inclusion or securing seats in parliament, or some grants or scholarships. It has more to do with their dignity, enabling them to participate in the public sphere without shame, and liberating them from social and religious stigma of being ‘untouchable.’

Sadly, most Dalit advocates and politicians have forgotten this agenda and are hankering after power, prestige and money. A handful of Dalit elites are enjoying all reservation quotas meant for poor Dalits.

Thus the government should come up with welfare policies whereby each citizen can live with freedom and dignity. Until this happens, women, Dalits, Janajati, Madheshis, and minority religious and linguistic groups have no option but to continuously raise voice against the state, so long as they continue to be treated as outsiders.

Social inclusion should also be promoted as an idea to ensure welfare of a broader section of the society instead of serving the interests of certain elites or caste groups. But the inclusion policies must also not disturb social harmony.

The Nepali state must also do more to enable every deprived group—Dalits, women, Janajati, Madheshi, backward class, the disabled—to enter the national mainstream.

The author is pursuing an MPhil in sociology from Tribhuvan University

girithezorba@gmail.com

You May Like This

Less than half paddy plantation in 10 Tarai districts

KATHMANDU, July 29: Tarai, known as the bread basket of Nepal, has not seen even 50 percent of paddy plantation... Read More...

Equal responsibility of all parties for holding election – NC leader Singh

KATHMANDU, April 15: Nepali Congress leader Prakash Man Singh has said that all parties have equal responsibility of making the... Read More...

Talk less, engage more

I wanted to show them how it’s done but never gave them the space and time to practice it themselves Read More...

Just In

- Shrestha nominated as Chairman of NCC's Advisory Council

- Take necessary measures to ensure education for all children

- Nepalgunj ICP handed over to Nepal, to come into operation from May 8

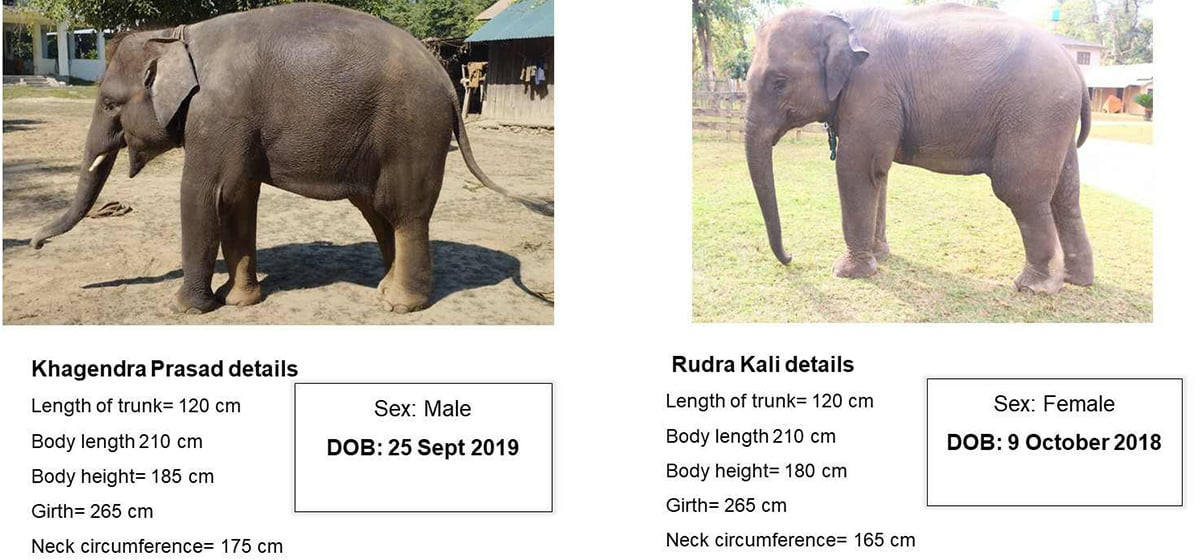

- Nepal to gift two elephants to Qatar during Emir's state visit

- NUP Chair Shrestha: Resham Chaudhary, convicted in Tikapur murder case, ineligible for party membership

- Dr Ram Kantha Makaju Shrestha: A visionary leader transforming healthcare in Nepal

- Let us present practical projects, not 'wish list': PM Dahal

- President Paudel requests Emir of Qatar to help secure release of Bipin Joshi held hostage by Hamas

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment