OR

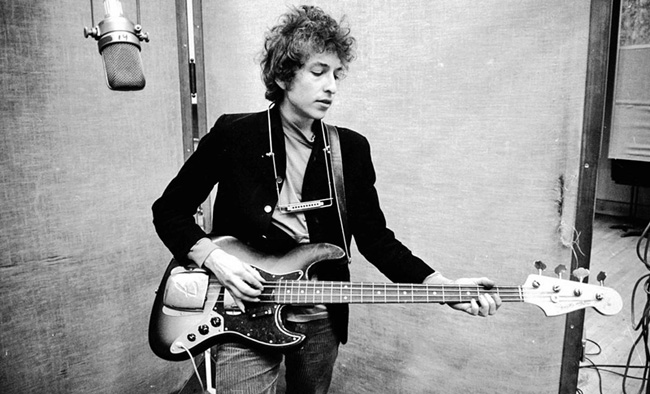

Bob Dylan in the eyes of an Eastern Himalayan

Published On: December 23, 2016 04:44 AM NPT By: Peter J Karthak

The Nobel Ceremonies of 2016 are now over. Bob Dylan, born Robert Alan Zimmerman, in Duluth in 1941, and a Minnesotan from Hibbing, received the year’s Nobel Prize in Literature. But he remained quiet, incommunicado and unresponsive throughout. He is known, like Miles Davis, to spurn and boo their audiences quite habitually.

Patti Smith, 70, seemed to represent the laureate at the Nobel ceremonies and faltered while singing Dylan’s ‘A Hard Rain Gonna Fall.’ That was in such a poor taste, the King and Queen of Sweden having to sit out the entire seven-minute musical mayhem so royally, stoically, even clapping. It was a scene of rare lese majeste, and the tribute song was a mess in its very second movement.

‘I’m sorry!’ was all Patti Smith said all along. The song’s lyrics and melody are powerful enough: a singer can keep her weeping aside.

Bob Dylan is two years older than me. I remember the mid-April evening in Darjeeling town, in 1964. I was walking down the lane from Robertson Road after signing a contract for my band, The Hillians, at the Planters’ Club for its forthcoming gala evening. Just as I neared the ABC Restaurant, I heard a new song. It had the refrain of ‘Blowin’ in the wind.’

Then I remembered Father EP Burns mentioning this song the day before in class while lecturing us on the Romantic Poets. I wasn’t listening properly, so I lost the reference to the line and John Keats – whatever!

I entered the restaurant, my evening hangout. I was a regular there, to drink tongba and relish its fiery fried meat. I knew the Tibetan owner, a refugee lady of noble birth in Lhasa, and I ran credits with her, too, when I was broke.

Then I saw the tall, slim, fair and beautiful Tara Mullick in one corner. It was she who was playing this 45rpm record on her portable Philips. Tara was from Loreto Convent, our ‘sister college’ and North Point’s counterpart in every college activity. She was one of the burgeoning ‘protest people’ of the town, much after what Bob Dylan and Joan Baez were doing in America. She was from a notable Indian family, and was doing all sorts of stuffs she wasn’t supposed to be doing. I sort of liked her, she being my occasional dancing partner at our college, St. Joseph’s. We sat together, drank potent tongba that evening, munched momos and listened to the new song.

But the song disappointed me. Its singing and instruments sounded to take me back to The Flintstones and Square Wheels. The voice, coming from a 23-year-old singer (I was 21), would fail the first auditions at the American Idol today: It sounded so old and unmusical. Bob Dylan played a rickety six-string acoustic guitar and blew on his mouth organ (now called harmonica). The words were poetic and protestive, yes, but its music took me to the Stone Age.

For I was doing the opposite in those days. I was an excellent mouth organ player myself. My favorite was a Vest Pocket on C Major. As a farm boy, I played tunes on green and fresh cardamom leaves, and made green bamboo-reed ‘bimbili’ – a sort of piccolo – and played it all over the village. But I had discarded harmonica and acoustic guitar in town. I was dreaming of a Univox organ and had electrified my band, with three loud electric guitars. We sang, not wailed. But here was an unusual singer who declared, ‘The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind.’

What answer, man?

And which wind, Senor Jose?

In reality, as well, a band could never sing and play a Bob Dylan song. Dylan was never a performing band music. I tried playing the melodies of his songs. But dancers automatically equated the tunes to the words of the songs.

‘C’mon, Peter! The Hillians can do better!’ Cyrus Billimoria shouted from the dance floor. Every pair agreed, and I had to switch over to ‘Little Honda’ by The Beach Boys.

‘Now, that’s better!’

Bob Dylan has sung all genres of songs – Rock, Folk, Country, Gospel et al – and composed his music in the phases of his developments as an artiste over the decades.

He is also the only one still traveling, performing, recording and creating new melodies and lyrics.

So he deserved the Nobel Prize in Literature, 2016.

But Dylan isn’t alone in the genres of serious and elevated songwriting. Decades before him, Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger had raised the standard bars of lyrics to poetry. His own contemporaries – Paul McCartney, John Lennon, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Paul Simon, Leonard Cohen and many other stars – raised songwriting many rungs above. One can’t either avoid the names of Little Richard, Robert Johnson, Fats Domino, Hank Williams, Hoagy Carmichael, Otis Redding, Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, Dolly Parton, Cat Stevens, Donovan, Gordon Lightfoot, John Denver, Johnny Paycheck, Kris Kristofferson, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Judy Collins, James Brown, John Prine, Paul Anka, Neil Diamond, Frank Zappa, Andy Garcia and scores of other iconic music-makers in so many diverse disciplines.

One can also define their colors and nationalities, and the schools of music they developed to enrich the music of the modern world. If any names are missing, it’s because the list is long, indeed.

If Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for 2016, it’s because he has outlasted all others in the field. The revolutionary Lennon-McCartney partnership was over by 1970, poetic Leonard Cohen took long breaks, and Paul Simon is a deliberately slow composer, and most others diversified to other interests and many passed away.

Therefore, in conclusion, it is Bob Dylan – the only constant troubadour still in the business of lofty and idealistic creativity in Pop Music – who represents all the uplifting singers, musicians, songwriters and their novel interpretations which changed modern popular music for all time to come. High literature in modern ‘intelligent’ music has so many other metaphysical architects and sound-breaking stylists. Pop music became intellectualized in the 1960s, and its metamorphoses continue in Bob Dylan’s creativity, among others’.

Thus, we say our fond farewell to the post-WWII Eisenhower era of ‘itsy bitsy teeny weeny’ and ‘bebop-o-lula’ meaninglessness and enter the brave world of New Music, beginning in the 1960s, which the Nobel Committee has finally recognized – in 2016.

pjkarthak@gmail.com

You May Like This

Nepal eyes for third straight victory in SAFF

KATHMANDU, Dec 29: High-flying Nepal, which has almost booked its place in the semifinals of the Women's SAFF Championship, will take... Read More...

Rasuwa witnessing an increase in tourist arrivals

RASUWA, Nov 10: Rasuwa, one of the districts hardest hit by the 2015 April earthquake, has been witnessing a gradual... Read More...

House meeting postponed for half an hour

KATHMANDU, June 20: Today's meeting of the Legislature-Parliament has been postponed for half an hour after Nepali Congress lawmakers demanded... Read More...

Just In

- Prez Paudel solicits Qatar’s investment in Nepal’s water resources, agriculture and tourism sectors

- Fire destroys 700 hectares forest area in Myagdi

- Three youths awarded 'Creators Champions'

- King of Qatar to hold meeting with PM Dahal, preparations underway to sign six bilateral agreements

- Nepal's Seismic Struggle and Ongoing Recovery Dynamics

- Shrestha nominated as Chairman of NCC's Advisory Council

- Take necessary measures to ensure education for all children

- Nepalgunj ICP handed over to Nepal, to come into operation from May 8

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment