OR

Economic development packages of goods and services that became prerequisites of prosperity and affluence have ravaged our shared social, cultural and ecological ties.

Nepal’s pathway towards development is a mixed bag. We brought to fore the prejudices of caste, gender and ethnicity, but ignored the shockwaves of modern day development. The economic development packages of goods and services that became the prerequisite marker of prosperity and affluence has entirely ravaged our shared social, cultural and ecological ties and turned us into the victims of planned poverty. Nobody is serious and will ever take the accountability for horrible environmental damages we will encounter very soon in the future.

Ivan Illich, an Austrian philosopher, who writes about destructions wrought by modern industrial society in the third world, is relevant in our context. Illich’s thoughts are illuminating but they were not received well. His stimulating schema on modern-day economic development, health and the idea of deschooling has had a profound impact. In his short but shrewd essay, ‘Development as Planned Poverty’ published in The Post Development Reader (1997) Illich talks about four ‘cs’ of service industry that has enhanced the larger unequal efficacy of economic development in underdeveloped countries—classrooms, calories, cars and clinics.

Market imperatives in classrooms, calories, cars and clinics increased incessantly after 1980s and highly polarized Nepali society in terms of receiving these services and the subsequent categories formed therein. Moreover, the consumptions of these services also became a part of social prestige which directly affected not only the poor but also the divided power-seeking class. These developments also weaned away whatever little social welfare was being advocated by the state. To borrow Illich’s arguments: “Once the Third World has become a mass market for the goods, products and processes which are designed by the rich for themselves, the discrepancy between demand for these Western artifacts and the supply will increase indefinitely. The family car cannot drive poor into the jet age, nor can the school system provide the poor with education, nor can family refrigerator ensure healthy food for them…’

Schools of divide

Classrooms are major sites of contention for creating programmed individuals in the service of the dominant ideology of the day—in this case varied forms of capitalism. In the name of education, classrooms implant multiple divisive specializations and separate individuals in terms of skilled and unskilled laborers creating high wage gaps and conferring different social and cultural capitals. Education, contrary to its normative goal, has institutionalized discriminatory provisions and actions. For instance, anyone who fails to attain mechanized institutional knowledge is left in the lurch. To cite Illich again: “Schools rationalize the divine origin of social stratification with much more rigor than churches have ever done”.

In Nepal with mushrooming privately owned schools and colleges the public educational institutions and the social diversity of students, one could find in them before 1980s eroded significantly creating twin spheres of citizenship. The children acquired education based on the strength of their parents’ purse and not necessarily on their merit. In fact, average aspiring middle-class parents invest all their working lives trying to fend for the school education of their kids.

Food for thought

Another area that defines development is nutrition. It is pathetic that calorie intake of certain food items are privileged over others. The fact that in Nepal many traditional sources of nutrition have been done away with in favor of those that serve both political and corporate class interest turns the debate on nutrition on its head. For instance, the clarion call by development wallas that Karnali region of Nepal is suffering from hunger and therefore sacks of rice need to be dropped to save their life is faulty. A closer look at the rice politics of Karnali suggests that such food items received as donations only enhance the dependency and kill local production. The locally grown rice is used for fermenting liquors. When the largely produced market food replaces the production of natural staple, this discourages farmers from farming. They opt for market demand or mobility takes place in off farming sector. This creates a declination in the farming and food production which has a spiral effect.

Consumption of food is a new marker in measuring poverty. But this can be misleading as what is nutritious remains contested and is shaped more by the market forces which is further reinforced by mainstream development discourse. Going back to some four decades economist and agronomist mocked farmers for being subsistent and encouraged them for overproduction of cash generating farming by using the modern breeding seeds, chemical fertilizers and pesticides. This not only resulted in the desertification of land but also made farmers ‘criminals’ for supplying poisonous food. Now, once again the promotion of so-called ‘organic farming’ has proved that whatever our farmers traditionally practiced in the past was humanly and genuine.

Commodity culture

Another important indicator of development is car (of course privately owned). For us cars became an ideal of social prestige. The supply and the consumption of cars are increasing every day in Nepal, which contribute significantly to the state treasury. For this the tarred concrete roads are being constructed everywhere and has become the fundamental priority of our development. The burgeoning supplies of cars are creating a dreadful damage to our ecology. The poisonous toxic these vehicles emit are horribly polluting our air and the roads are stifled with these smokes. We are confronting smog all around every day. The reports suggest that the quality of air we breathe in Kathmandu is one of the worst in the world. Despite this, we all are trapped in demanding cars because it is a social luxury in manifesting our progress and affluence.

Similarly, the increment of the mega buildings of private clinics and hospitals has weakened government hospitals. The profession of doctor no longer remained a Samaritans job. If someone falls seriously ill, then it has a knock-on effect on other members of the family as the medical expenses slowly but surely dry up one’s resource. Further, the public-private dichotomy creates an internal hierarchy among kin members as it is your financial capacity that determines your access to quality medical services. The human body itself has become a mere object of a commodity through which billions of rupees is raked in. And all the money flies to private hospitals.

We cannot overlook what we attained in terms of everyday consumption after 1990s in comparison to our predecessors. The term economic development was all inclusive in each and every plan and program we made since 1950s. But we have not critically scrutinized the services we received from these institutions—private or public. Are our development paradigms environmental and public-centered? Or are they only being executed without a thought for its after effects?

The authors are assistant professors at Kathmandu School of Law

You May Like This

Development Committee asks govt to increase development expenditures to 90 percent

KATHMANDU, Dec 8: Today's meeting of the Development Committee (DC) under the Legislature-Parliament has directed the government to increase the... Read More...

Mobile application development course to start in Nepal soon

KATHMANDU, Dec 8: Mobile application development curriculum in Bachelors degree will be introduced for the first time in Nepal soon. Read More...

India always ready to cooperate with Nepal's development endeavors: Rae

CHITWAN, Aug 23: India's Ambassador to Nepal Ranjit Rae has said India was ever ready to cooperate in Nepal's development... Read More...

Just In

- FinMin Pun addresses V-20 meeting: ‘Nepal plays a minimal role in climate change, so it should get compensation’

- Nepalis living illegally in Kuwait can return home by June 17 without facing penalties

- 'Trishuli Villa' operationalized with Rs 100 million investment

- Unified Socialist rejoins Lumbini Province govt following ministry allocation

- Police release ANFA Vice President Lama after SC order

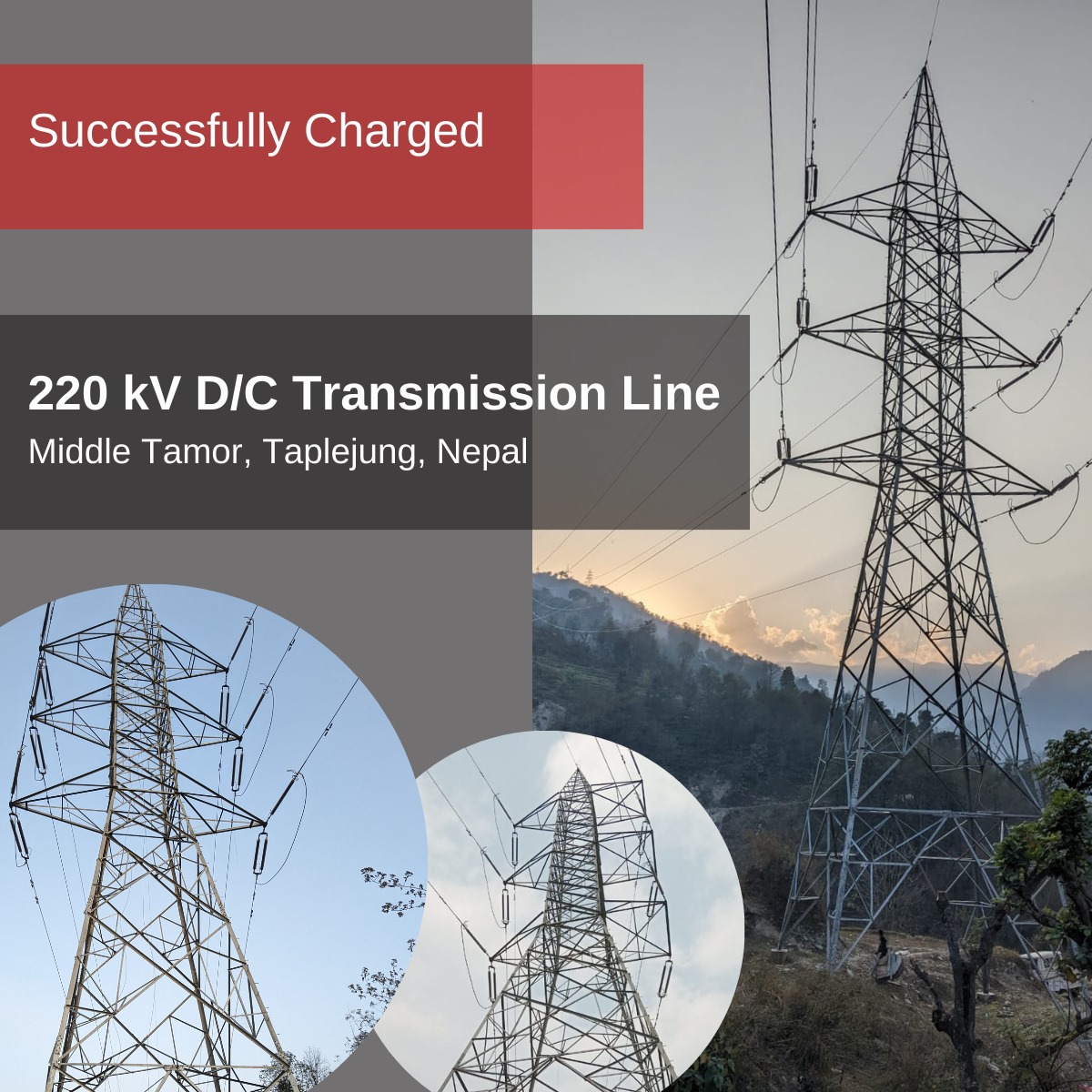

- 16 hydroelectric projects being developed in Tamor River

- Cosmic Electrical completes 220 kV transmission line project

- Morang DAO imposes ban on rallies, gatherings and demonstrations

Leave A Comment